Minority Postdoctoral Fellows Join the Ranks

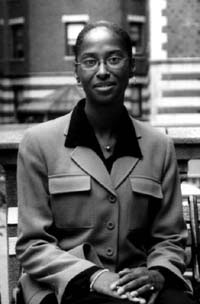

Two new Minority Postdoctoral Fellows have joined Teachers College this fall. Joya Carter, Ph.D., who just completed her doctoral studies at Syracuse University, will be continuing her research on inclusive schooling. Detris Honora, Ed.D., is a graduate of Harvard University Graduate School of Education in the department of Human Development and Psychology. Honora focuses her research on factors that influence school achievement among adolescents.

"Last year I was thinking about what I wanted to do this year," said Carter. "I thought every university was like Syracuse in the way they dealt with inclusion issues. I looked at tenure track positions that had the same paradigm I was coming from."

In addition to looking into several tenure track positions, Carter heard about TC's minority postdoctoral program. "When you think about having a year of time where you have the support -- financial, time, mentoring -- it is a year to jump start my career," Carter said. She will use her time at Teachers College to expand on a project she started in Syracuse. In order to better define Africana feminist thought, she is currently looking at ten African-American women who have received doctorates in inclusion or special education and are pursuing academic careers.

"Several of the women went into major white universities," Carter said. "Some of the issues were that they weren't socialized -- transitioning from a grad student into the demands of a professor and a writer."

Carter's research is a kind of reflective study of her own experience as an African-American woman moving toward an academic career. Her dissertation looked at the young children learning and growing without stereotypes and prejudices in a mainstream classroom setting. Carter likens the experience of African-American grad students coming out of historically black colleges, seeking positions in predominantly white universities, to the young children she studied.

Coming from a family of educators in Atlanta, Carter did not originally expect to work in education. As an undergraduate, she wanted to be a psychologist. However, a temporary teaching position made her realize she really loved working with children.

"My interest in inclusion came with the issue of over-representation of students of color in special education classes and under-representation in gifted programs," Carter explained. Her dissertation gives examples of how inclusion works.

"Nowhere do I walk away with the idea that it doesn't work, but it looks different in different classrooms," she said. Similarly, she continued, "Black colleges have a different perspective of how scholarship is defined."

The historically black colleges, Carter said, are focused primarily on teaching and service. "It is hard to teach seven classes a year and meet the demands for writing," she added. "It is hard to be connected to the community and still do ten publications in three years." Her research will look at the issues of creating an entry for women of color into white universities.

In a similar vein, Detris Honora is using this time as a postdoctoral fellow to get back to doing more research and writing. For the last three years, she has been working as an assistant professor at Southern University, a teaching institute. Aside from teaching four classes per semester, she was advising more than 40 students.

One of her proudest accomplishments was getting undergraduate students involved in scientific research. "During my first year, five of my undergraduate students had their papers accepted for professional conferences at the local and national level," Honora said.

"Right now, I am attempting to expand on the study I did for my dissertation," she said. In that study she looked at how poor and minority adolescents view the future and how their views of the future shape their academic performance. As part of that research, Honora looked at goal-setting and planning behaviors, as well as how optimistic the young people were in their ability to plan their strategies and whether they believed they would reach their goals.

As a postdoctoral fellow Honora will be collecting data on a larger group of rural and urban students in the South. "For someone from a small rural community to have accomplished what I have, it isn't hard for me to reflect on what got me here and find out what helps other adolescents in similar rural communities to set goals," she said.

She will track students from seventh grade through their high school graduation, helping them to plan and strategize how to reach their goals. The students will be compared to a control group that will not learn these same strategies.

Her previous work showed that high achieving girls set more goals, were more optimistic and had more strategies than any other group in the study. "When I looked at students' thoughts and feelings about the future, I found that African-American boys had a negative view of the future regardless of their achievements," Honora said. "Even though half were achieving at higher levels, they still didn't think they would reach their goals. They felt that no matter how hard they worked they wouldn't accomplish what they set out to accomplish."

These boys, she said, believed that although they were good enough to excel in school, education would not help them.

While at TC, Honora hopes to track the students she followed for her dissertation study to see how their goals, expectations and views of the future may have changed over time. Her current research will explore the connection between academic achievement and perspective on the future as well as the connection between that perspective and risk behavior exhibited by adolescents.

Published Tuesday, Sep. 18, 2001