Pursuing equal educational opportunity in a post-Brown world

TC's Equity Symposium asks: Can the state finance suits fill the gap as the Supreme Court retreats on integration?

“The decision last June by the U.S. Supreme Court to invalidate racial balancing plans in two school districts was the clearest signal yet that the nation has entered a new, post-desegregation era, in which the vision espoused in Brown v. Board of Education – that of a federal judiciary with an abiding commitment to integrated schools – is no longer the operative condition. This shift will alter the national education landscape – and indeed has altered it already – for decades to come.”

That assessment, offered by TC President Susan Fuhrman at the start of the third annual symposium of TC’s Campaign for Educational Equity, was widely shared by the many presenters, discussants and panelists at the two day event, titled “Equal Educational Opportunity: What Now? Reassessing the Role of the Courts, the Law and School Policies after Seattle and CFE.” On the question of precisely how the education landscape has changed, and how those changes will affect the lives of students, communities and the nation as a whole, there was far less consensus.

The Symposium began with a brief overview of the Court’s decision in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District, in which plaintiffs challenged the constitutionality of voluntary integration plans adopted by school boards in

By a 5-4 margin, the Supreme Court ruled in June that both of these plans were unconstitutional. However, a different majority of the Court indicated that other voluntary integration plans that do not assign individual students by race, but which rely instead on magnet schools, redrawing of attendance zones, strategic site selection of new schools and other such mechanisms would be permitted. Justice Anthony Kennedy provided the swing vote in each outcome.

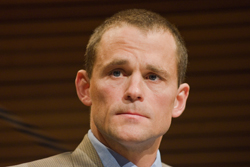

For Ted Shaw, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the Court’s invalidation of the

“There is a constant struggle over the place of race in this country, and now diversity has become the only rationale that the Supreme Court has respected,” Shaw said, referring to Justice Kennedy’s opinion that while schools do have a “compelling interest” in maintaining the diversity of classrooms, measures by districts to ensure diversity cannot use the race of individual students as a basis for making classroom assignments. As a result of the decision, Shaw said, many programs are now at risk – including scholarship programs, pipeline programs, and PhD programs.

“These programs are at risk because of this Orwellian consciousness that says race consciousness is race-ism. The legal discourse is dishonest, and the social and political discourse is dishonest,” he said.

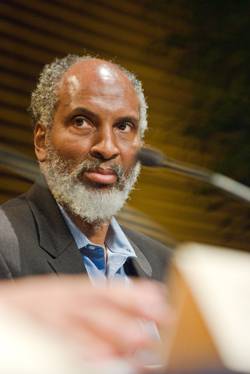

“Things are not so bad,” said john powell, Executive Director of the Kirwin Institute for Race Ethnicity at

Those viewing the

For example, Anurima Bhargava, Director of the Education Practice, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, said that under Kennedy’s opinion, the vast majority of the programs used in

“It’s not just about race anymore,” Bhargava said. To ensure public schools that benefit all children, school assignment plans should also target balance poor students and rich students, low-performing students and high performing students, and other demographics.

Rhoda Schneider, General Counsel and Associate Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Education, said that she’s been telling districts not to panic in the wake of

“

Michael Rebell, Executive Director of The Campaign for Educational Equity, made the case that educational adequacy litigation – the wave of law suits in state courts that over the past two decades have won increased funds for poorer school districts – is the current best hope for pursing equal educational opportunity. He laid out a framework for expanding and securing the changes wrought by these suits, which have prevailed in 21 of 27 states since 1989.

“The experience of the last 30 years has proved the pessimists wrong,” he said, referring to the reaction by many education and civil rights advocates during the 1970s when a previous Supreme Court ruling suggested that state courts would be the appropriate theater for safeguarding educational opportunity. “I’m here to say that the experience of the education adequacy cases proves there is life after bad Supreme Court decisions.”

Rebell said that state courts are in fact better equipped than the federal courts to enforce students constitutional rights, because state constitutions provide them with a direct and positive command to do so, while the role of the federal court plays a more reactive role. As elected officials, state judges also have a higher “democratic pedigree,” Rebell said, and they are more familiar with local conditions – both social and political.

Courts, in turn, are in a better position than legislatures to provide the remedial staying power to ensure successful implementation of school reforms, Rebell said. But he was careful to note that the courts could not do it alone; that in fact, the best scenario is one in which the three branches work together, each in the capacity for which it is best suited. The courts offer the ability to uphold a principled perspective, Rebell said; legislatures offer the needed policymaking expertise; and the executive branch brings the day-to-day ability to oversee implementation.

Eric Hanushek of the Hoover Institution, a long-time critic of the education adequacy movement, took issue with Rebell, questioning how courts can start with a clause in a state constitution that requires common schools and end up with a judicial order that schools equip citizens to be jurors capable of evaluating DNA evidence. Hanushek warned the mostly pro-adequacy audience to be careful what they wished for, arguing that judicial decisions don’t necessarily provide the recovery or extension of democracy.

The symposium’s final session brought together two former judges in adequacy cases -- John Greaney, Justice Supreme of Massachusetts’ Judicial Court and Albert Rosenblatt, formerly of the New York Court of Appeals – along with a former West Virginia governor, Robert Wise, and a former state legislator, Joyce Elliott, who had chaired the Arkansas House Education Committee. The four – all veterans of adequacy litigation -- agreed that adequacy cases are judicial as well as political processes, and that harmonizing relationships with other branches of government is crucial to the successful implementation of remedies. All took issue with the opinion of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in the Seattle decision, agreeing instead that at times judges do indeed have to be willing to be “social engineers” in order to be faithful to constitutional commands.

Greaney offered the most emotional endorsement of that idea when he was asked by the panel moderator, Jay Worona of the New York State School Boards Association, to tell the audience why he was wearing black. The graying judge with the patrician New England demeanor said he is a fan of country music and of Johnny Cash in particular, and then proceeded to recite some lines from one of Cash’s signature songs:

I wear black for the poor and the beaten down,

Livin’ in the hopeless, hungry side of town,

I wear it for the prisoner who has long paid for his crime,

But is there because he’s a victim of the times.

Listen to podcasts of all symposium proceedings. Now available through iTunes U.

Published Monday, Nov. 26, 2007