Filed Under > International

Educational Equity at the Village Level

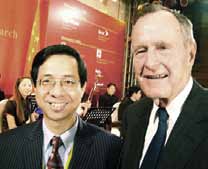

TC Professor Mun Tsang is leading the fight to fund schooling for China's rural poor and through his Center for Chinese Education is helping drive faculty research and outreach projects in the Asian nation.

Many people trace the origin of China

But the boom times haven’t benefited everyone equally. The standard of living in many of China

“What’s happening in China today with education is like what was happening in the United States China

In 1993, at a conference convened by the World Bank, Tsang himself was the first to call attention to this issue. In two subsequent papers, published in the Economics of Education Review and the Harvard Education Review, Tsang called for China to institute a “regularized, substantial and transparent scheme of intergovernmental funding” for China Yunnan Province

“The Schulz Foundation already was funding efforts like this in Africa ,” Tsang says. “I happened to know the Chair, and I told him, ‘Hey, this problem is just as bad in China

Because Teachers College made the decision to take no money for its overhead costs out of the Schulz grant, “every penny went to the children,” Tsang says. He also instituted a system under which parents received their assistance money through the schools, “so that nothing was siphoned off.”

The program was a success. The dropout rates in the project schools in Yunnan Province China

Tsang has been widely recognized for his work in this area, receiving, among other honors, the designations “Honorary President, China Economics of Education Society” and, in 2006, “Changjiang Scholar”—the first time the latter award, which is a national professorship, was given to someone in the education field. He also received the Richard Swanson Excellence in Research Award from the American Academy of Human Resources Development for his research on access to and financing of basic-literacy programs in China China U.K. , Canada , Korea , Japan , Spain , Australia and the U.S. China

And the Center maintains a wide range of other activities, including collaborations with a diverse group of TC faculty members (Henry Levin, Tom Bailey, Kevin Dougherty, Anna Neumann, Fran Schoonmaker, Lin Goodwin, Lambros Comitas, Francisco Rivera-Batiz, Aaron Pallas, Herve Varenne, Delores Perin, Jeff Henig, George Bond, Charles Harrington, Carolyn Riehl, Luis Huerta, Craig Richards, Lucy Calkins, Stephen Peverly, Bruce Vogeli, Robert Monson, Xiaodong Lin and others) whose expertise ranges from anthropological and cultural studies to education technology. Under the Center’s auspices, some 50 visiting Chinese scholars have come to TC, and some 200 primary and secondary education leaders and some 50 university leaders have participated in education seminars at the College. The Center is also a source of learning and financial support for many TC students.

“China is obviously a big, important country, and an actively engaged and constructive bilateral relationship with the United States

Millions of Chinese schoolchildren and their parents would surely agree.

Published Monday, Jun. 8, 2009