Filed Under > TC Community

Shaping Education around the World

From the College's earliest days, TC's approach to education has taken the wider world into consideration

In the spring of 1899, when James Earl Russell offered a course at Teachers College titled “The Comparative Study of Education Systems,” he was so concerned no one would show up that he persuaded the College’s trustees to offer three $500 scholarships as bait. Asked by TC’s President, Nicholas Murray Butler, whether the requirements—a reading knowledge of French and German—weren’t rather stiff, Russell responded, pessimistically, that at least the class “looked well in the catalogue.”

As it turned out, no one need have worried. Thirty-four students showed up on the first day. Russell himself would become known as the father of the field of comparative education. And Teachers College formally committed to an international focus that has since helped shape and reshape education in the United States

In a sense, the College had already embarked on that path. Both Russell and John Dewey were heavily influenced by European thinkers like Friedrich Froebel and Johann Pestalozzi. With waves of immigrant families arriving in New York City at the beginning of the twentieth century, they and others at the College had a heightened sense both of how the rest of the world might shape American society and, therefore, of how TC might work to shape the world.

It was under Russell, by then TC’s Dean, that the legendary Paul Monroe created the College’s International Institute in 1923. One of four core centers established under Russell, the International Institute, which would last until 1938, brought together a star-studded cast of scholars that included Monroe; Associate Director William F. Russell (James’ son); Dewey; Isaac Kandel; George Counts; William Heard Kilpatrick; Will McCall; and Thomas Alexander. They traveled and studied education systems in countries ranging from China and the Soviet Union to Bulgaria , Iran , Denmark and Sweden

The Institute also granted scholarships for studying abroad. In 1923, TC entered into an arrangement that allowed its students to spend a semester studying at the University of Paris

But perhaps the Institute’s most important function was to serve as both a resource and a drawing card for foreign students. By 1923, there already were more than 250 of these at TC, hailing from 42 countries. By 1927, the number had grown to 457 and by 1932, just before the Depression, to 1,200. By the time the Institute closed, it had drawn some 4,000 foreign students to TC.

A substantial number of these students came from China , including a remarkable group of educators who, inspired by what they learned at TC, would lead the modernization of China Morning Village Normal School in Nanjing Shanghai and a Tao Research Association, with 18 branches throughout China

Meanwhile, Dewey, Monroe, Kilpatrick, McCall and others visited China China

TC’s involvement with China Latin America , and also financed the graduate studies of international students at TC.

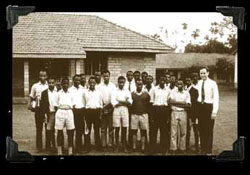

Under IED’s aegis, the College launched its Teachers for East Africa (TEA) program in 1961 with a grant from the International Cooperation Agency, precursor to USAID. TEA recruited and trained American teachers for educational service and provided technical assistance to help increase the number of local qualified teachers trained in Kenya , Tanzania and Uganda

Another IED initiative was TC’s first Afghanistan Kabul University Afghanistan

The project’s work was brought to a halt by the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan Pakistan

In 2003, after the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan , TC launched a second Afghanistan Project, led by Barry Rosen, then TC’s Executive Director of External Affairs and one of the 52 Americans who had been taken hostage in Iran

During the 1980s, Japan Tokyo New York

In 2006, however, the campus received official accreditation, meaning that graduates now can use the credits they’ve earned to apply for higher degrees at Japanese universities. Meanwhile, the school has begun offering other programs, including a summer travel experience in Cambodia

There is, of course, much more to the TC international story. Karl Bigelow played an important role in the creation of UNESCO in the wake of World War II. George Bereday developed a comparative education approach that combined description, interpretation, juxtaposition and comparison. Richard Wolfe, R.L. Thorndike, Elizabeth Hagen and Harold Noah helped to develop methods of measurement that have since enabled true comparisons of the education systems of different countries, including the development of international student achievement tests such as TIMSS and PISA

Then, too, TC’s international work has focused not only on the work of schools and teachers, but on education writ large—that is, on factors such as students’ physical and mental health and their families and community lives. In fields such as nursing and nutrition education, TC educators such as Mary Swartz Rose, Adelaide Nutting and Isabel Maitland Stewart helped establish curricula around the world, and current faculty such as Isobel Contento, who leads the College’s nutrition program, continue the process of international exchange.

There is one other particularly important footnote to the story. In the mid-1990s, the College combined its two flagship international programs—Comparative and International Education and International Education Development—into the new Department of International and Transcultural Studies (ITS). Today the department’s programs are among the largest of their kind in the United States West 120th Street

Published Monday, Jun. 8, 2009