The Hip-Hop Hypothesis

To sell inner-city teens on science, Christopher Emdin is meeting them on their own cultural turf

To sell inner-city teens on science, Christopher Emdin is meeting them on their own cultural turf

by Patricia Lamiell

So I sit in the back of this science class unconscious

everything that my teacher(s) spitting is nonsense

I wanna raise my hand but I avoid the conflict

Plus if I raise my hand, I’m not the one he’s gon’ pick

So I sit here, mind in another place, rhyming to myself, different time, different space

Displaced, ’cuz I can’t keep pace, can’t wait for the bell so I can make my escape.

Christopher Emdin, Assistant Professor of Science Education, is rapping “Reality,” a song he wrote for his group, Ghosttown, for a visitor to his office.

“That’s the kid I’m trying to reach,” he says. “The kid in the back of the classroom, staring into space and mentally halfway out the door but very much attuned to any sign, however subtle, that he belongs in school.”

Emdin sees hip-hop as teachers’ last and best chance to reach disaffected students. “Hip-hop is owned and spawned by marginalized voices,” Emdin writes in the introduction to his book, Urban Science Education for the Hip-Hop Generation, published last spring by Sense Publishers. “Secondly, because it is mostly created by urban youth, it provides insight into the inner workings of their thoughts about the world, and, consequently, is a tool for unlocking their academic potential.”

Emdin fervently believes that the academic potential of these youth is not only unrealized, but unique. That’s why he became a science teacher in the Bronx, then a doctoral student in urban education at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. (His dissertation, “Exploring the Contexts of Urban Science Classrooms: Cogenerative Dialogues, CoTeaching and Cosmopolitanism,” won the Phi Delta Kappa International Outstanding Dissertation Award.) It was also why co-founded Marie Curie High School for Medicine, Nursing and Health Professions in the Bronx. (Marie Curie, which serves an entirely African American and Latino student population, was recently named a Bronze School by U.S. News & World Report).

Emdin came to TC in 2007 seeking a bigger pulpit. His course, “Hip-Hop and the Cultural Studies of Science Education,” focuses not only on hip-hop’s cultural importance but also on the urgent necessity of approaching young students with respect for their culture.

Emdin’s use of rap in the classroom has drawn the attention of a local TV station and the rap music press, but three-minute segments on the evening news don’t begin to capture the depth of his approach. The first thing he stipulates about hip-hop is that it’s more than just the art of rapping original rhymes over beats. It’s also more, he says, than the sum of other art forms hip-hop has created, which include beat-boxing, break-dancing, b-boying, dee-jaying and graffiti; more than its influence on fashion, advertising and even politics. Rather, hip-hop is an entire culture created in the 1970s by African American urban youth who were outside the American mainstream. Many were dropouts or had been kicked out of school (a fate Emdin himself narrowly escaped as a teenager in Brooklyn). Yet, he writes, these kids, so alienated from formal education, wrote rap “on the front steps and in the cafeterias of New York City public schools.” They were learning from the streets and creating ways of interpreting the world that were expressed in their art and that then transcended it. Those modes of thinking, acting and communicating blossomed into a culture.

Emdin’s TC colleague Marc Lamont Hill, Associate Professor of English Education, has studied that transformation since the early 1990s, when hip-hop exploded onto the streets and radio stations of every major city in the country before going global. “Culture isn’t just about what you read or listen to,” Hill says. “It’s more complex and dynamic than that. Culture has to do with habits of speech, mind and body.” As a culture that was created by and now defines urban youth, Hill says, “hip-hop informs how they think and see the world.” Hip-hop has grown popular with some high school and middle school educators in urban areas who use rap in English language, music and math classes or graffiti in art classes. Emdin’s innovation, Hill says, is using it both as a window into young students’ minds, and a model for scientific inquiry and classroom culture. “Chris’s work represents the next phase of hip-hop based education,” Hill says. “He’s turning it into something that’s field-changing.”

Indeed, Emdin believes science is hip-hop, precisely because of its subversive nature. One of his science heroes is Galileo, who was convicted of heresy by the Catholic Church in the 17th century for supporting the Copernican theory that the earth orbited the sun. What is science, Emdin asks, if not a revolutionary way to interpret the world? If urban youth are learning from their experiences on the street and manipulating knowledge in new ways, might they not interpret scientific phenomena, like Newton’s Laws of Motion, in a similar fashion? They might, Emdin reasons, if they were taught by someone who respected hip-hop culture and saw it as a valid way to think, learn, act and communicate.

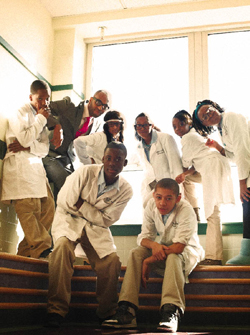

The strategy has worked at Marie Curie High School, where Emdin remains a major presence. In an inaugural class of 100 students in 2004, Emdin says, 85 went to college, and 45 to 50 are majoring in the sciences. The numbers have since been equally impressive. “Kids have a limited scope of their own power,” Emdin says. “Once they realize that who they are can also be how they learn, nothing is impossible.”

For a taping at Marie Curie by ABC News last May, Emdin wore a black suit and tie. The professional attire seemed calculated to say to the students: If Chris Emdin—the Brooklyn-raised public school student who almost got kicked out of high school—can become a college professor, a scientist and a rapper, so can they.

Clearly he has maintained the connection between those two selves. For classroom discussion, Emdin has adapted the cipher, a highly codified system of hand and body gestures and verbal cues used by rap groups when they collaborate on songs. The rules of the cipher are the same as on the street: Everyone gets to speak. No one is interrupted or denigrated. Repeating someone else’s idea is against the rules. A rapper who is ready to relinquish the floor uses a prescribed verbal cue or a hand gesture.

At Marie Curie and elsewhere Emdin works across New York City, students follow these rules when collectively solving a science problem or working out disagreements in the classroom. The students have even written and shared rap songs as study tools for the New York State Regents exam, boosting Marie Curie’s test scores. In this way, Emdin says, hip-hop in the classroom is “co-generative and co-taught.”

Emdin acknowledges that many people—even some within hip-hop culture—reject some rap, its most popularized art form, as gratuitously violent and misogynistic, and he calls some mainstream rap overly commercialized and “commodified.” But this is only a “thin slice of hip-hop music, and an even thinner slice of hip-hop culture.” And while he does not condone the glamorized violence of “gangsta rap,” he notes that the form, like all art, is drawn from the creator’s experience.

Last May, with the ABC camera rolling and a student beating on a table to create a hip-hop beat, Emdin improvised a rap:

See how I mix the science and the hip-hop,

I keep flowin’ like this and I just don’t stop.

“The failure of education is its failure to find ways to meet existing demographics,” he said later. “Hip-hop is the biggest cultural phenomenon in history. We’re at a point where it’s the only way to go.”

To view Emdin and Hill in “Education and the Hip-Hop Generation,” an event sponsored last winter by the Vice President’s Office for Diversity and Community Affairs at TC, visit http://bit.ly/aF3oD8.

Published Wednesday, Dec. 15, 2010