Filed Under > Convocation

At Commencement, an Educators' Call to Arms

The College's 2011 graduates are urged to pursue both excellence and equity

“I don’t just want you to teach the children of our society – I want you to fight for them.”

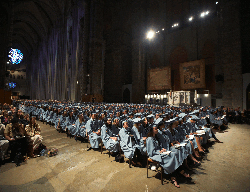

Former New York Times columnist Bob Herbert was addressing the second of two master’s degree ceremonies, but he could well have been speaking for all those who took the podium during Teachers College’s two days of commencement exercises on May 17th and 18th in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

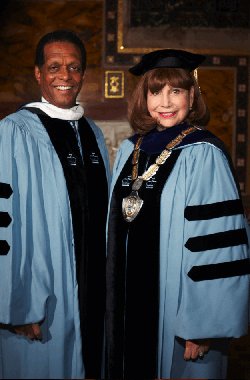

Speaker after speaker -- from the three recipients of TC’s Medal for Distinguished Service (Herbert; Baltimore public schools chief Andres Alonso; and Stanford University education scholar Linda Darling Hammond), to the two student speakers, Akilah Reynolds and Traci Leigh Johnson, and TC President Susan Fuhrman herself -- sounded the call for graduates to advance the cause of education, both by creating new and better solutions to learning challenges, and by fighting a rising tide of inequality in American society.

“The talent for blending new ideas with well-grounded knowledge in order to produce effective new educational strategies and methods is embedded in TC’s DNA,” said Fuhrman, who over the course of two days reminded the more than 2,000 master’s and doctoral degree recipients that the College was the birthplace of many fields of inquiry, including comparative and international education, special education, social studies, and the study of gifted children. She predicted that “TC’s dynamic partnerships with local schools in Harlem and communities throughout the world will enable us to promote equity and transform urban education in a time of scarce resources,” and called on graduates to” join our global network of innovative leaders in the task of shaping the learning century.

” Still, Fuhrman did not mince words in describing the current climate. “We are fighting to reverse a nationwide high school dropout epidemic that condemns more than a million American teenagers to lives of poverty, despair and drift,” she said. “We are fighting to reduce ever widening gaps in education opportunity and scholastic achievement within our country – even as we simultaneously struggle to catch up in math and science literacy with competitor nations.” The battle extends to the health arena as well, which includes “a global obesity epidemic fed by a toxic brew of economic, cultural and behavioral forces.

” To succeed in combating these forces, Fuhrman said, “we cannot bicker and blame our way to success. We can – and we should – put our heads together, pool our perspectives and specialized areas of expertise, and craft powerful and enduring solutions to the challenges facing our nation and our world.”

Others described the nation’s educational health – and its condition more generally – in starker terms. “There is real suffering out there,” said Herbert, the long-time social commentator for the Times and other venues. “The American dream itself is on life support,” he said, with “an extreme and growing” income gap between the wealthiest members of society and working and poor Americans.

That state of affairs has come about because of organized, well financed attempts to systematically dismantle the Great Society public assistance programs of the 1960s and New Deal programs dating back to the Great Depression, Herbert said. “When you fire up the wrecking ball for Medicare and Medicaid and Social Security at the same time that you’re shielding the wealthy and the great corporations from having to pay their fair share of taxes, you’re doing great harm to the ordinary and working people, the struggling families of America,” he said, drawing applause from the audience.

Educators must apply their content knowledge, pedagogical skills and research-based innovations to the many problems in public education, Herbert said, “but they must also organize and form alliances to counter the “outsized political influence of the very wealthy.” Teachers need to “let the world know that money isn’t the be-all and end-all,” he concluded, his voice rising as the audience began to clap again, “and that your commitment to serving the interest of those children will not be derailed.”

Linda Darling-Hammond, Stanford’s Charles E. Ducommon Professor of Education and a former TC faculty member, began by sketching a portrait of American education nearly 125 years ago, at the time of the College’s founding. A cadre of “scientific managers” was looking to make schools more “efficient’ via a “factory model regime of prescribed lessons and pacing schedules,” a heavy regimen of standardized tests, and merit pay for teachers – the very things that some education reformers are now proposing.

“Does any of this sound familiar?” Darling-Hammond asked.

But countering that tide of small-mindedness, Darling-Hammond said, TC teachers, school leaders and professors were pioneering a very different approach founded on “intellectual inquiry, hands-on projects, activity-based curriculum” and other learner centered practices.

Today, the College is again a bulwark as “the profession of teaching and our system of public education are under siege from another wave of scientific managers who have forgotten that education is about opening minds to inquiry and imagination, not stuffing them like so many dead turkeys – that teaching is about enabling students to make sense of their experience, to use knowledge for their own ends, and to learn to learn.”

All of this is occurring at a time when “our nation is on the verge of forgetting its children,” Darling-Hammond said, citing a U.S. poverty rate for youth that is higher than that of any other industrialized country, a defense budget “larger than that of the next 20 countries combined” and greater disparities in wealth than any leading country. “

Our leaders do not talk about those things,” Darling-Hammond said. “They simply say of poor children, ‘Let them eat tests.’ ” Yet amid all the talk of international test score comparisons “there is too little talk about what high-performing countries actually do: fund schools equitably, invest in high quality preparation, mentoring and professional development for teachers and leaders, and organize a curriculum around problem solving and critical thinking skills.”

Nor do other nations seek to solve their education problems by firing teachers and principals and closing schools, Darling-Hammond said – a practice she likened to “deciding that if the banks are failing, we should fire the tellers.”

Darling-Hammond, who said she is “enormously proud to be a continuing member of the TC community,” urged the graduates to take heart it in knowing that, as Martin Luther King said, the arc of history is long but it bends toward justice. She reminded them that, in Robert Kennedy’s words, “each time a person stands up for an idea… he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope,” and concluded, “I think you in advance for each ripple of hope you will create.”

Perhaps the most hopeful note was struck by Alonso, who reminded his listeners of Henry James’ declaration that “to believe in a child is to believe in the future.” Alonso recapped his own story of coming to the United States from Cuba as a boy who spoke no English, earning a Harvard law degree and then leaving a promising legal career to become a special education teacher in Newark.

“Twenty five years ago, I changed course in my career and I became an educator,” he said. “It has been the single most important and right decision in my life. In the schools where I have taught and led, the act of educating children is often a struggle against many things that belie our belief in children. You believe and you serve – I salute you as a brother in arms.”

Alonso said that his own teachers – including his parents, who gave him a birthday gift of four books when he was six years old – “helped calibrate my moral compass” and “are responsible for what I have done right.” The memory of their positive influence moved him to seek an arena in which he could exert a similar effect – one he has found in his current position. The Baltimore school system, he said, is “the fulcrum of everything good that can happen in the city. We touch, every day, not only more than 80,000 kids, but through them also their families, their communities, and every social institution that responds to them.”

Alonso celebrated the system’s accomplishments during his tenure, which includes students across all categories achieving their highest-ever outcomes on state exams, highest-ever graduation rate and lowest-ever dropout rates; elementary and high school students in all sub-groups making Adequate Yearly Progress; a dropout rate that has fallen by half; and, for the first time in decades, a gain in the total number of public school students.

“We have given hope to the city about what is possible in our schools,” he said, but added that “everything feels fragile. We know that every setback means we go back to the bottom of the hill again.”

He concluded by urging the graduates to “be true to your essential self on behalf of yourself and your students, and yet remain open to what others will teach you, especially the kids and families you will serve” – and to be “willing to put and leave skin in the game to make certain things happen that are often very hard to accomplish given the conditions of our schools and communities, without becoming cynical or leaning to blame others for the inevitable defeats along the way.”

Traci Johnson, who received her master’s degree in International Development and Education (with a concentration in Peace Studies), spoke at the second master’s degree ceremony of “the transformative potential of education.”

Johnson said her work at TC provided her with her first encounter with both the evidence and consequences of poverty and educational inequity. She learned, she said, that “inevitably we will enter spaces that are shaped by inequity,” requiring us to “question our own roles in supporting, ignoring or dismantling” the structures that perpetuate injustices.

TC graduates leave the College not only with an excellent education and training, but also with the tools to construct their own agenda for social justice, Johnson said. She encouraged her classmates to embody both of those legacies in their personal and professional lives.

Earlier in the day, student speaker Akilah Reynolds, who was receiving her degree in Counseling and Clinical Psychology, said that at TC she learned that “before counseling others, I first had to learn about myself,” because “our work demands the kind of empowerment that comes only by looking at our own identities.”

Reynolds said that, partly as a result of her time at TC, she has been able to overcome a childhood fear of public speaking. But she has also realized the need, as a professional “to practice what we preach.

“Some people are fascinated by action heroes like Superman and Batman – but heroes are people who believe strongly in a cause and walk the walk,” she said. “Heroes embodied the things they profess.”

She reminded the audience that the date – May 17th – was the 57th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which began the process of striking down school segregation. That decision began, she said, “with people who believed in their right to access to equality quality education” and had the courage to pursue it at great personal peril.

For her own part, Reynolds said, she has come to realize that “courage is having fear but doing something despite that fear” – particularly “doing something radically different, like those who fought for equality in education.”

Reynolds said that being at TC has helped her to “challenge her fears,” and said that she persevered in her work here “because people helped me recognize that on the other side was the evolved me I wanted to become.

“Change is infectious,” she concluded. “It starts with one person who wants something so much they dare to be different. Change starts with you and me.”

The student presentation at the doctoral hooding ceremony was not a speech but a musical performance. Victor Lin, who received his doctorate degree in music education at the ceremony, played a violin arrangement of the traditional folk song, “The Water is Wide.”

Published Saturday, May. 21, 2011