Research in Practice: Finding Answers in the Classroom

Research in Practice: Finding Answers in the Classroom

Why, really, is it important to teach in ways that build on children’s cultural backgrounds?

That question surfaced in a recent working group of the Teachers College Inclusive Classrooms Project, in which New York City teachers explore strategies to help the special education students entering their classrooms in growing numbers. Discussions are guided by TC faculty members who are experts on these topics.

“One gentleman, who taught deaf children, saw no value in finding out if his students came from rich or poor neighborhoods,” recalls the group’s facilitator, Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, TC Assistant Professor of Education. “He said deafness was their defining characteristic, so focusing on their socio-economic status would be pigeonholing them.”

Noting that most of the teacher’s students were black, Sealey-Ruiz wondered whether he might be using sign language that differed from an African-American vernacular that children used at home. After all,TC faculty member Karen Froud, Associate Professor of Speech & Language Pathology, has used an imaging technique called electroencephalography to show that the brain often processes dialects

as wholly distinct languages.

“In the end,” Sealey-Ruiz says, “he realized he needed to know more about his students than just that they couldn’t hear.”

To Vice Dean A. Lin Goodwin, that story distills an important facet of TC’s philosophy: “Even apprentice teachers have valuable insights from working with students of all abilities, but through the knowledge of our faculty, we provide scaffolding that moves them beyond show-and-tell to a much deeper, research-based understanding.”

“It’s our job to help our students understand that a good theory can generate a thousand practices,” adds Celia Oyler, who co-directs TC’s Elementary Inclusive Preservice Education Program. “Teachers need alternative approaches for all the different challenges they face.”

Even the newest teachers gain insights that can help shape the practice of their more experienced colleagues. “I draw a distinction between research on practice and research in practice,” says Ruth Vinz, the Enid & Lester Morse Chair in Teacher Education, and Professor in English Education. “It is powerful to engage in research with a school community on ways to study learning and teaching. That creates an ongoing cycle of inquiry in which teacher-researchers continuously look closely at their work and take action from what they learn.”

In a sense, the process of research in practice begins with assessment—a word too often seen as a proxy for relentless testing, but at TC denotes a deeper process of learning how students think.

“The word ‘to assess’ literally means ‘to sit beside,’” says Associate Professor of Education Molly Quinn. “When you sit side by side with your student and see what’s happening, you get a very different sense of not only assessing, but teaching, generally.”

Vinz, who founded and directs TC’s Center for the Professional Education of Teachers (CPET), leads a unique project called the Secondary Literacy Institute (SLI), which works with New York City public school teachers to create “DYOs” (for “Design Your Own”)—periodic assessments that are embedded within the schools’ curricula rather than relying on the city’s standardized tests. These curriculum-embedded assessments are rooted in what’s actually being taught by teachers, informing the next segment of the curriculum and the instructional steps teachers should take.

But assessments are only a start in guiding instruction. “Teachers can create an environment that fosters creativity, but they must be good observers of children,” says Susan Recchia, Co-coordinator of TC’s Integrated Early Childhood Program and Faculty Director of the Rita Gold Early Childhood Center. Recchia calls the Center’s play-based approach the “emergent curriculum,” from the Italian Reggio Emilia Approach. “Teachers must watch to see what children are interested in, what ideas they’re bringing to the group. Then they try to respond,” Recchia says.

Ernest Morrell, Director of TC’s Institute for Urban and Minority Education, recalls an East Los Angeles English teacher whose students only wanted to talk about life in East L.A. OK, Morrell suggested, let them write about life in East L.A. In the resulting project, called “A Day in a Life,” students published and described their work at national conferences. Boston teachers adapted the approach, creating a readers’ theater that Morrell calls “the most powerful thing I’ve seen in 25 years.

“We need powerful educators, too, to tell their stories,” he says. “It’s in sharing these rigorously researched narratives of dynamic classroom practice that we have the best chance of replicating that practice.”

That’s part of the thinking at the Teachers College Community School (TCCS), a K-8 public elementary school in Harlem that TC opened this past fall with the New York City Department of Education.

TCCS exists first and foremost “to meet our moral obligation to provide the best possible education for children in the community where we live and work,” says Nancy Streim, TC’s Associate Vice President for School and Community Partnerships, but the school is also “a place where we can show how the cutting-edge knowledge that we have here can be infused into regular public education.”

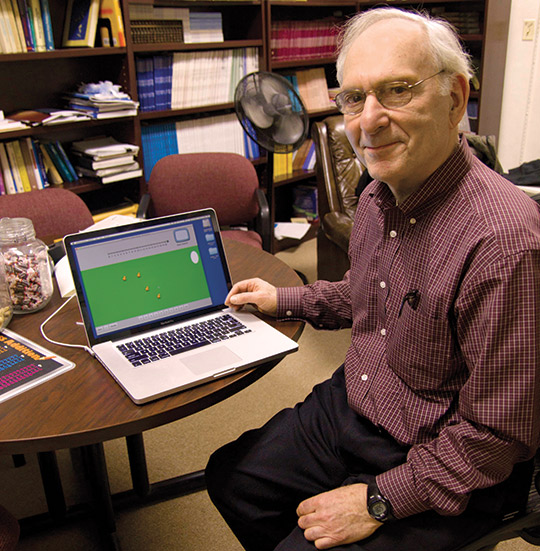

That effort includes the use of tools such as MathemAntics, a computer-based math program developed by TC faculty member Herbert Ginsburg, and the presence of TC’s Zankel Fellows—students who, in exchange for a stipend, volunteer in city schools and community organizations. Next year, TCCS will offer health and social services to parents and the community.

“With graduate students in social work, education and other areas, we can cost-effectively provide the wrap-around services schools need,” says TC President Susan Fuhrman. “TCCS, and Teachers College in general, are demonstration sites for the future of education in this country.”

Published Friday, Apr. 13, 2012