Rethinking Adversity

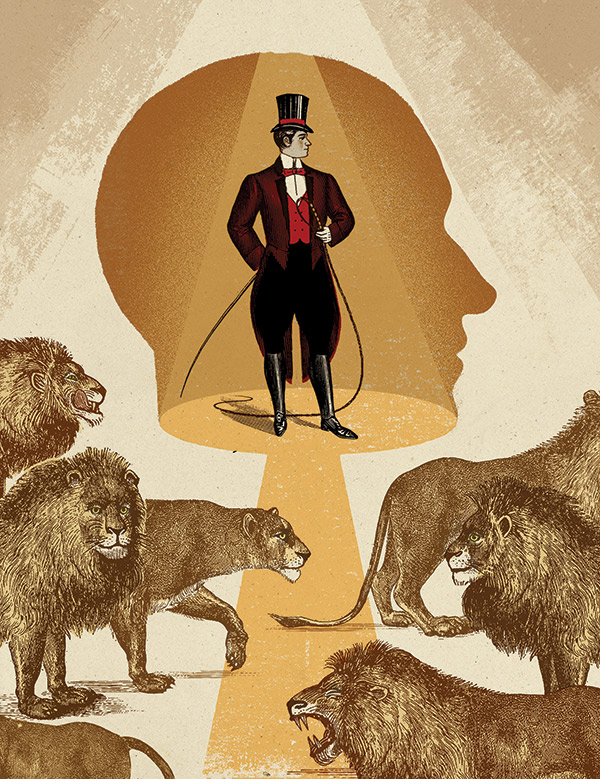

Illustration: Carlo Giambarresi

Illustration: Carlo Giambarresi

TC psychologists are focusing on both people's internal ability to cope with adversity and external social forces that create adverse circumstances.

Being human entails facing difficulty. Since Freud, psychology has sought to understand how adversity harms us and can make us stronger — and to help people cope more effectively. This effort has focused both on factors inside the individual and external social forces such as inequities in wealth and power, and discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation and class. Many Teachers College psychologists have been at the forefront of both kinds of work — from the front lines of the global refugee crisis to the impact of police violence against minorities, to the nexus of environment and genetics. They are leaders in ...

Rethinking Adversity

Part One: How We Cope

Speaking of the Unspeakable

The term “school psychologist” may convey a focus on the everyday, but that’s been anything but the case with Philip Saigh and Marla Brassard. During the 1970s, Saigh taught at the American University of Beirut (AUB) and served as a therapist at AUB Hospital. When civil war broke out, he began seeing children who’d survived bombings and terrible injuries and witnessed death. Their symptoms included nightmares, flashbacks, inability to concentrate, and preoccupation with illness and death. “They didn’t fi t existing models of classification,” he recalls. “I spent a lot of time in the library, reviewing similar cases seen after the two World Wars.”

Then in 1980, the American Psychological Association published a new adult diagnosis called posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and Saigh began constructing an interview to identify PTSD in children. The condition, often accompanied by — and confused with — depression and anxiety, is diagnosed only when symptoms persist for at least one month. Still, Saigh’s pool of children grew, and he began treating them with an adaptation of a technique called flooding, previously used to reduce students’ test-taking anxieties. A similar method had also helped American soldiers returning from Vietnam.

“Essentially, I asked kids to imagine aspects of their traumatic experience, gradually and for longer periods,” recalls Saigh of the treatment, now called Exposure Therapy and used in many countries. “The idea is to expose the child to the feared situation in his or her imagination, under controlled conditions. It’s like getting back on the horse after being thrown.”

Illustration: Gianni Di Conno

Illustration: Gianni Di Conno

Parental neglect is the worst form of emotional abuse. When children realize the people on whom they depend for their well-being simply care, they feel alone in the world.

Marla Brassard has made equally important contributions to understanding psychological abuse and neglect, which, she says, “equal all other forms of maltreatment, short of death and brain injury, in terms of damage to the developing brain, psyche, social functioning, health of a child and life outcomes.”

In 1983, Brassard — an expert witness in death penalty cases involving defendants with documented histories of abuse and neglect, and in custody cases involving allegations of psychological abuse — co-chaired the first international conference on psychological abuse with Stuart Hart of Indiana University. They developed a set of definitions and assessments — including one that identifies maltreatment based on observing 20 minutes of parent-child interaction.

Understanding Trauma in Children: Philip Saigh

Understanding Trauma in Children: Philip Saigh

Philip Saigh has refined understanding of PTSD, finding that children diagnosed with it have greater anxiety and depression and lower verbal IQs than those exposed to trauma who don’t have PTSD; also, that the latter closely resemble children never exposed to trauma at all. “The PTSD diagnosis counts,” Saigh says. Thanks to him, so does the treatment.

Psychological abuse includes calling children derogatory names or saying things like “having you ruined my life.” Neglect includes extreme emotional unresponsiveness and other things parents don’t do that would normally promote healthy brain development and social functioning. Neglect is also embedded in every other form of abuse.

“If you surprise your father in the garage, and he throws you up against the wall, you’ll forgive him,” Brassard says. “But if he recognizes you and means to hurt you, you feel alone in the world because the person on whom you depend for your safety and well-being is communicating that he really doesn’t care about you or is a threat to your well-being.”

Parental psychological abuse and neglect vary greatly in frequency, intensity and duration. A worst-case scenario: when infants are fed and changed but not hugged or talked to. Left to make sense of a frightening world and regulate their own emotions, these children typically have very low IQs and may appear mentally retarded, yet “they’re often incredibly street-smart — people who’d be our best survivors in a world war.”

Currently, Brassard is revising forensic guidelines to help front-line social workers identify and report caregiver psychological abuse and neglect. The intent isn’t punitive. “You can’t go around arresting people for being mean to their kids,” she says. “Parents don’t need more critics — it’s hard, lonely work, so you’ve got to set up supports.”

Can We Become More Resilient?

In 2004, George Bonanno published powerful new evidence that most people recover quickly and fully from emotional loss and trauma: Among a representative sample of those who had been inside the World Trade Center on 9/11 or seen others die, more than half were psychologically indistinguishable from people who were miles away, with no signs of PTSD. Another sizeable percentage recovered over a longer period, while only between 5 and 30 percent displayed chronic PTSD.

Rebuilding Community: Lena Verdeli

Rebuilding Community: Lena Verdeli

“There is an old Zulu saying, ‘People are people within people,’ meaning personhood is experienced and expressed within community and social roles,” Lena Verdeli says. “In displacement situations, Group IPT helps break social isolation and create a sense of community. We’re experts on the method; local therapists and clients know what triggers their depression and trauma-related behaviors and feelings.”

Bonanno and others have since replicated those numbers with survivors of everything from natural disasters to spinal cord injury. Most recently, using Department of Defense data on 140,000 soldiers, Bonanno found that 83 percent experienced little change in trauma from before deployment through their return. Surprisingly, multiply deployed soldiers fared even better.

But why isn’t everyone resilient — and how to help those who aren’t?

Bonanno believes resilience requires “regulatory flexibility” in responding to changing environments. “We decide how to respond to different challenges and threats by assessing what’s happening,” he says. “Assessment requires asking, sometimes repeatedly, What do I need to do?, What am I able to do? and Is it working?”

We may not do this well if we have become overly conditioned to respond to a particular situation. For example, brain development that governs emotional self-regulation begins earlier in children who suffer chronic neglect. “It helps them survive, but probably at a cost of flexibility ,” Bonanno says. “You become a go/no go kid — you either don’t react to stress, or you do, full out.” Some combat veterans similarly learn hypervigilance and hair-trigger response to sudden sound and movement — vital for battlefield survival but disastrous back home.

Bonanno thinks better adaptive responses can be learned or re-learned. TC’s Resilience Center for Veterans and Families, which he directs, aims to create such interventions, in part based on people’s profiles before trauma occurred.

“We need to know these baseline distinctions to be able to provide appropriate treatment,” Bonanno says.

Meanwhile, two other TC psychologists, Lena Verdeli and Lisa Miller, focus on tw o very diff erent factors in resilience: community and spirituality.

Verdeli, Founding Director of TC’s Global Mental Health Lab, believes that “personhood is experienced and expressed within the context of community and social roles” and that restoring community is critical for the world’s 65 million refugees. Many are so anxious and depressed that they cannot care for themselves and their families, even when food and shelter are provided.

Illustration: Ellen Weinstein

Illustration: Ellen Weinstein

People are amazingly resilient. We typically recover quickly and fully from loss and trauma; restoring community helps us cope with disaster; and depression can lead to spiritual awakening.

Verdeli has adapted a therapeutic approach called Group Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) that is proving successful in humanitarian emergencies worldwide. IPT focuses on triggers of depressive episodes — grief, life changes, conflicts. In 2003, Verdeli and her research partner, Kathleen Clougherty, trained young high school-educated villagers to conduct group IPT sessions in AIDS-ravaged southern Ugandan communities. They used IPT again in northern Uganda in 2007 with teens displaced by civil war. In randomized clinical trials, people’s locally defined mental health problems improved beyond expectation.

Verdeli has since trained professionals as well as laypeople in Haiti and Colombia. Lebanon, with a vast refugee population, is implementing its new national mental health strategy in consultation with her. She also led adaptation of methods for the World Health Organization’s new Group IPT manual and leads trainings for WHO, nongovernment organizations and mental health workers affiliated with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

“We’re harnessing and strengthening natural healing mechanisms,” she says. Spirituality, too, may provide community — through a belief in something larger than oneself.

Early in her career, Lisa Miller joined a 20-year study of mothers with a history of depression and found that those practicing a religious faith were less likely to suffer from recurrence of the condition. Miller subsequently linked regular spiritual practice to a thickening of the brain’s cortex, which thins in chronically depressed people.

Miller calls her work “traditional” in providing a scientific basis for something timeless: a “universal spirituality that can be lived beautifully through a religious faith or through family, nature or personal practices.” Her students have traveled to the Southern California sanctuary of the Ojai Foundation, to chant at the vernal equinox, and to India, to meet the Hindu spiritual leader Mata Amritanandamayi Devi. Miller believes such “spiritual multilingualism” can help “overcome the illusion of hard-core separateness that leads to war and other global threats.”

Most recently, Miller has cited biological evidence that “depression is often the doorway to spiritual awakening”: for example, the finding that in people with a lifetime history of depression who self-report an active spiritual life, a gene that inhibits the “reuptake” of the neurotransmitter serotonin — the same mechanism employed by many antidepressants — is more active.

Part Two: Changing an Unjust World

You’re OK, and I am, too

There’s been a slow yet steady acknowledgement that people identify in all kinds of ways, and that all facets of identity are worthy of being recognized and affirmed,” says TC psychologist Brandon Velez.

That hopeful statement owes much to TC counseling psychologists Derald Wing Sue and Robert Carter, who have led efforts to change the climate around social identity. Their colleague, Laura Smith, has emerged as a national voice on poverty, while new faculty such as Velez and Melanie Brewster are building on their efforts.

In 1996, Sue drew hate mail for televised remarks to President Bill Clinton’s Race Advisory Board urging Americans to “acknowledge our biases and preconceived notions.”

Demonstrating Racism’s harm: Robert Carter

Demonstrating Racism’s harm: Robert Carter

People often remain stressed from race-based encounters, Robert Carter finds. “If you can show that minorities have been socially and psychologically injured, and you win a damages suit, that will get attention and perhaps stop the negative behavior. Recognition of racism and its harm will likely take more time than I have, but I hope one day it will happen.”

“In academia, my research findings on racism hadn’t caused a stir, but now people said, ‘You’re just a racist of a different color.’” Sue shakes his head. “My wife said, ‘You live in an academic bubble. You need to help ordinary folks understand racism.’”

Sue has since almost single-handedly made “microaggressions” a lay term, delivering his message that these unintended slights toward people of color, gay and transgender people and women are often more harmful than overt racism and hate crimes.

Microaggressions wound so powerfully, Sue argues, because they reveal society’s unconscious biased assumptions. “When I’m asked, as an Asian American, ‘Where were you born?’ and I say, ‘Portland, Oregon,’ and they follow up with, ‘No, where were you really born?’ — I’m seen as a perpetual alien, not a true American.” Unspoken microaggressions can be even more toxic. The white person who clutches her purse when an African American enters the elevator, Sue says, holds the same stereotypes that result in unwarranted police shootings of black men.

Can microaggressors change? Most resist because “looking at their unconscious biases would assail their sense of being good, moral and decent individuals.”

In his most recent book, Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence (Wiley 2015), Sue describes roadblocks to such self-scrutiny. They range from the fear that “whatever I say or do will appear racist” to passivity when it comes to actively combating racism. “If you object to a favorite uncle’s racist joke, others may hush you up,” he says. “If you voice concern in the workplace, you may be branded a bleeding-heart liberal. A well-intentioned society has many ways to keep us in our places — and to reward us for not rocking the boat.”

Where Sue has tried to prompt a change of heart, Robert Carter has sought to create legal redress for race based harm and stress.

Illustration: Beppe Giacobbe

Illustration: Beppe Giacobbe

TC’s Brandon Velez sees “a slow yet steady acknowledgement that people identify in all kinds of ways, and that all facets of identity are worthy of being recognized and affirmed.”

“If you bring a complaint that something at work made you uncomfortable sexually, you do not need to show intent,” Carter says. “It’s enough that you were uncomfortable; corrective actions could be taken in the organization or by the court. But there are no guidelines for racial claims, and when the claim is racial, one has to show the defendant’s intent.”

Carter has developed the first and only instruments for measuring race-based traumatic stress and the different kinds of racism people are exposed to. The categories range from “avoidant racism” (refusal to offer minorities a job or a loan) to “hostile racism practices” (police profiling, stop-and-frisk). Carter, who has served as an expert witness in racial discrimination cases, published his instruments in 2013, 2015 and 2016 in the journals Psychological Trauma and Traumatology — “a big step, because the people and the courts require expert testimony to be based on accepted scientific evidence in your field.”

Both Melanie Brewster and Brandon Velez have widened the discourse on harm inflicted around social identity. Brewster is interested in adaptive skills that promote mental health among members of marginalized groups such as bisexuals, LGB people of color and transgender persons. Cognitive flexibility, for example, combines an awareness of options in difficult situations with the willingness to consider them. Bicultural competence is the ability to navigate with ease among both one’s own and other social identity groups.

Brewster is also interested in the stresses on those who openly declare themselves atheists. In 2014, she published an edited volume, Atheists in America (Columbia University Press), and has explored whether atheists who attend non-religious churches such as Oasis or the Society of Ethical Culture experience less stress than those who don’t.

Velez studies the effects of prejudice on Latina/o LGB people and others who identify as members of multiple minority groups, a focus that became all too relevant after the June 2016 Pulse nightclub mass shooting in Orlando, Florida. “Many victims were people who were doubly marginalized,” he says.

Velez is trying to untangle complex questions: Is it true, as is often claimed in popular discourse and scholarship, that heterosexist prejudice is more prevalent among racial and ethnic minority communities? If so, are LGB people of color exposed to more of such prejudice? Might sexual minority people of color be less susceptible to heterosexism because they’ve learned strategies to cope with racial prejudice?

Microaggressions and discrimination are also directed at people on the basis of class — which is why, writing in American Psychologist in September 2015, Laura Smith called for her profession to support increasing the minimum wage.

Illustration: Pep Montserrat

Illustration: Pep Montserrat

Just as damaging as outright discrimination is stereotype threat — the burden of undertaking a particular task knowing that others expect you to fail because of your particular social identity.

Smith, whose family is from the central Appalachian Mountain region, explores issues of social inclusion and exclusion. “People who are marginalized and live outside access to civic protections, health care, and educational opportunities are precluded from reaching optimal levels of well-being,” she says. “If you address exclusion, you’re preventively addressing issues of emotional well-being rather than doing remedial work later on.”

In one study, Smith and her students found that poor students at elite higher education institutions frequently experience classist microaggressions by faculty and classmates: for example, in sweeping statements about the poor or working class as “the other”; in casual invites to go out for dinner; in comments about people on welfare. “These students constantly choose between concealing their class identities or coming out,” Smith says.

Increasingly, Smith’s efforts are focused on social change — particularly through participatory action research. “We don’t do studies on kids and community members — we do it with them, identifying issues of importance together. We include them as knowledge makers with something to teach others — by naming, as well or better than anyone else, problems in need of study in their own communities.”

The first step, Smith says, is to convince kids that they have skin in the game. “Research can seem super boring — what does it have to do with them?”

At a Bronx public school, Smith’s team helped teenagers conduct research that convinced the principal to institute courses on sexuality and sexual health.

“When you live life understood by the dominant culture as someone with nothing important to say, that seeps into your being,” she says. “So why do we do this work as counselors and psychologists? The theory is, let’s do something beyond the 50-minute therapy hour to more directly target silencing and marginalization.”

Just Business? (Mis)managing diversity in the workplace

Most organizations sty le themselves as “meritocracies” that award jobs and promotions solely for qualifications and results.

Confronting Stereotype Threat: Loriann Roberson

Confronting Stereotype Threat: Loriann Roberson

What should organizations do about stereotype threat? First, stop pretending it doesn’t exist, argues Loriann Roberson. Managers should be candid about others’ unjust attitudes and reduce threatening “cues” for at-risk employees — for example, by offering reassurance and guidance rather than a “sink or swim” approach, or by emphasizing the importance of skills not questioned by the stereotype.

So why, ask Caryn Block and Debra Noumair, are there “still very few women and minorities in senior leadership positions in organizations that hold power”? Why, despite the Civil Rights movement and the first black U.S. president, are 94.8 percent of Fortune CEO positions held by men and 95 percent held by whites?

Noumair, Block and three colleagues in TC’s Social-Organizational Psychology program — Loriann Roberson, Elissa Perry and Sarah Brazaitis — are in the forefront of answering those questions. Block and Noumair are coediting a special issue of The Journal of Applied Behavioral Studies on social equity as an organization change issue, while Block, Noumair and Brazaitis have been funded to create a TC initiative on the same topic.

The group’s hallmark is directly applying research and theory to practice and taking a systems approach to understanding diversity dynamics in the workplace, including in academia, companies and nonprofits.

Certainly they’ve confirmed that people continue to hold deeply entrenched stereotypes about others. Block co-authored a study — since cited nearly 900 times — showing that female managers viewed as successful were stereotyped as having hostile personalities. In a just-published study led by Perry, a fictional job applicant identified { adversity } as 60 years old was overwhelmingly perceived to be less competent, less motivated and less adaptable than an applicant identified as 29 years old, or a Millennial (or Generation Y). Yet when the applicant was described as a Baby Boomer, he fared comparably with applicants identified as members of the younger generation.

Such biases undoubtedly lead managers and colleagues to treat women, minorities and older employees unfairly. Yet the TC group has also documented another source of damage: from “stereotype threat” — the burden of undertaking a particular task knowing that others expect you to fail because of your race, gender, age or other social identity group. Numerous studies have shown that blacks, women and other oft -marginalized groups under-perform when expending vital mental energy worrying about failure or trying to disprove stereotypes.

In one study, Block and Roberson explored how female scientists respond to stereotype threat at different stages of their careers. They found that younger female scientists try to “bullet-proof” themselves by never making a mistake. Mid-career women scientists are more likely to challenge injustice or simply leave. Senior women are realistic survivors who strategically defend against stereotype threat but also try to be themselves and find meaning in their work. They may not always answer the call to “wear the women in science hat.”

“Stereotype threat isn’t just something to overcome in a given situation,” Block says. “The work, in forging a career, is how to manage that extra layer?”

Illustration: Jody Hewgill

Illustration: Jody Hewgill

Within organizations, people sometimes gravitate toward roles that are pre-baked into the system — team player, malcontent, foot-soldier — and that prevents them from realizing their full potential.

Roberson has conducted some of the major studies of diversity management. Programs that groom women and minorities for senior jobs typically fail, she argues, because even when managers act without prejudice, others in the organization hold stereotypes — and employees in stereotyped groups know it. The latter face a double whammy: they are handicapped by stereotype threat but held to an “impartial” performance standard that ignores the handicap.

“The presence of stereotype threat means that performance itself may convey biased information about a person’s true ability,” Roberson writes.

Many believe stereotype threat is “in the air.” Thus TC’s Executive Master’s Program in Change Leadership (XMA), which Debra Noumair founded in 2011 for mid-level executives tapped to lead and manage major change in their organizations, approaches discrimination as a systemic issue. The program teaches that change in any one area of an organization plays out across all levels, and that neat diagrams of reporting relationships and supply chains don’t capture “irrational, unseen” forces that thwart successful change.

Bias and exclusion occur at all levels, but insidious authority dynamics typically occur beneath the surface, Noumair says. Some people actively covet power, while others fear for their jobs or their ways of thinking and doing. They project disavowed aspects of themselves onto those whom they perceive as “the other.” Some labels —“team player,” “fixer” or “producer” — sound benign, while others — “loser,” “bully,” “provocateur” — suggest weakness, inappropriate anger, or lack of self-awareness. Both kinds of labels stick because those tagged with them have their own “Velcro” (Noumair’s term) for familiar, comfortable roles, which they enact on behalf of bosses and colleagues.

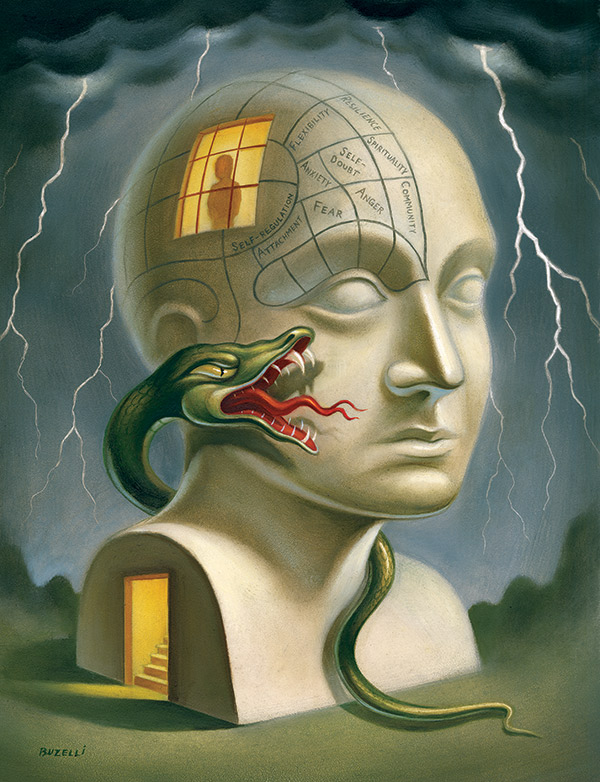

Illustration: Chris Buzelli

Illustration: Chris Buzelli

Being human entails facing difficulty. Since Freud, psychology has sought to understand how adversity harms us and can make us stronger —and to help people cope more effectively.

Sarah Brazaitis has vividly illustrated these interrelationships through her studies of white women, who, she argues, “occupy a unique position in our society : oppressed due to sexism but oppressors because of their white skin.”

White women help preserve white male privilege and power, Brazaitis argues, because they benefit from it. They are also positioned to disrupt it — but doing so would mean relinquishing their system-assigned roles. Where black mothers have raised their daughters to be strong, resilient and independent in order to face the challenges of a racist society, Brazaitis says, white girls are often taught unwittingly to give up their power, self-reliance and independence in exchange for protection and financial security.

“In group relations conferences… I have seen white women authorize white men as leaders and defend and protect white men despite their seeming irresponsibility, incompetence or even abusiveness,” she writes. “I have seen white women pair with white men insistently, repeatedly, often at the expense or exclusion of other women, both white and of color.”

Noumair argues that these different roles — superstar, team player, malcontent, foot-soldier — are pre-baked into the system and dynamically connected.

“You can’t have a star without a scapegoat,” she says. “Someone can’t be oppressed without an oppressor. Students in the XMA learn about covert processes and see that as the game-changer. They go back to their jobs feeling as though they’re wearing X-ray glasses — now they can see beneath the surface of their organizations. Now they can help people hold a more complicated view of organizational life and work to create more inclusive systems.”

“Our work provides people with tools to understand diversity dynamics in systems, rather than focusing on diversity as something that individuals do or do not have,” Block adds.

Everyone stands to benefit. White women, for example, might find themselves “freed to nurture and strengthen their sense of self-agency and authorization,” Brazaitis suggests.

Companies that “hire (and train) might recognize that “turnover among younger people is actually greater and more frequent,” Perry says, “so older employees may represent a better investment.”

And as Brazaitis writes, those in power might decide that “rather than each group fighting one another for scarce resources of power and authority, such collaboration could produce an ample supply to be shared among all.”

Part Three: How the Environment gets Under Our Skin

Ultimately, neither inner resources nor external forces alone determine success in coping with adversity. Or as TC developmental psychologist Jeanne Brooks-Gunn puts it, the old argument of “nature versus nurture” is a meaningless dichotomy. “What is interesting is the interplay between the two,” she says.

Illustration: Kevin Hong

Illustration: Kevin Hong

Neither inner resources nor external forces alone determine success in coping with adversity. Gene studies are showing literally, how poverty, discrimination and violence get under the skin to influence health.

At TC, Brooks-Gunn, who has co-directed several of the nation’s largest long-term studies of families and children living in poverty, and Laudan Jahromi, who explores enhancing social and emotional readiness among vulnerable groups of children and their parents, work this fascinating middle ground.

Brooks-Gunn’s studies have helped establish that disparities in wealth and other resources dramatically affect school and career success, health and longevity. More recently, she and others have drawn on this work to show, literally, how poverty, discrimination and violence get under the skin to influence health.

---

To support TC students working with these and other psychology faculty, visit tc.edu/supportpsych or contact Linda Colquhoun at 212 678-3679.

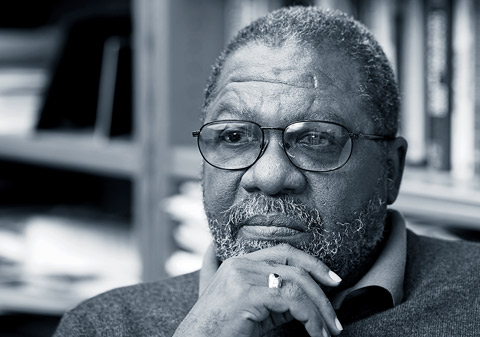

Addressing Genetic Vulnerability: Jeanne Brooks-Gunn

Addressing Genetic Vulnerability: Jeanne Brooks-Gunn

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn’s studies suggest genetic vulnerability to environmental stresses in some mothers who parented more harshly after the 2008 Recession; in others in poverty with severe postpartum depression; and in some children whose fathers have left home. “We can’t change the genome,” she says. “But if we create a better environment, we can change which genes are turned on and off.”

In one line of inquiry, she has focused on how adverse social circumstances affect biological markers such as telomeres — long regions of molecules that help protect the ends of chromosomes from degrading. In a 2014 study of African-American boys, Brooks-Gunn and colleagues found that telomere lengths of those living in more difficult environments were on average 40 percent shorter than for those living in more advantaged environments. In other work, conducted with biologists, demographers and economists, Brooks-Gunn has found that people with a genetic indicator associated with fewer dopamine receptors may be more stressed by poverty and other environmental conditions.

Now Brooks-Gunn is focusing on the epigenome — a kind of rheostat, or set of master chemical switches, that enhances or represses the expression of certain genes or gene groups.

“The epigenome is the reason why two identical twins, born with the same genetic markers, might have different health profiles at age 50 or 60,” she says. “They’ve had different experiences and their rheostats are quite different.”

New evidence suggests that some of what Brooks-Gunn calls “the rheostat sets” may be transmitted and even increased across generations.

“That’s huge,” she says. “After a generation or two, poor kids may, for example, get high blood pressure at higher rates not only because they live in negative environments, but also because they were born with rheostats altered by the experiences of their parents.” The same may be true for immune function and susceptibility to conditions ranging from colds to cancer — which would help explain why poorer people have shorter life expectancies.

Laudan Jahromi, who also operates from “a developmental/ ecological framework,” isn’t looking at genes — but she is interested in how children with autism (nature) and their immigrant parents cope with a special education system (nurture) that conducts business mainly in another language.

Currently, together with TC doctoral students like Christine Iturriaga, a longtime district special education chairperson, Jahromi looks at the stressors that face immigrant parents of special-needs kindergarteners as they begin navigating the special education system.

“We’re focusing on culturally diverse families to better understand how their experiences in the special ed system are different,” Jahromi says. “We are looking at potential risk factors like perceptions of discrimination, as well as aspects of cultural resilience, like familism [cultures in which family needs take precedence over those of individual family members]. We want to know whether families reporting certain ty pes of protective factors or barriers to special education have particular kinds of outcomes. Then we can figure out how to intervene.”

Nothing less than the futures of potentially productive human beings hang in the balance. “The pre-K to K transition establishes long-term patterns for children and their families, in terms of how they are going to engage with schools,” Jahromi says. “So we want to ensure it’s a healthy transition.” —Joe Levine

Teachers College psychology students are often key partners in the groundbreaking work of the College's psychology faculty. Below are stories of some of the talented psychology students who have earned TC degrees in recent years.

Teachers College Psychology Student Stories

Published Tuesday, Nov 15, 2016