Unconventional Wisdom: Paradigm-changing work at TC

Uncertainty Opens Minds to Life's Complex Texts

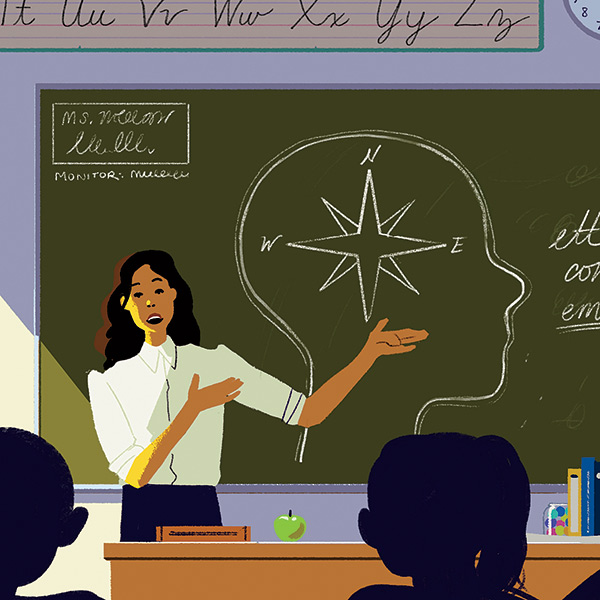

Some years ago, Bob Fecho challenged a classroom of young, Southern white women to defend mainstreaming novels by black authors into standard courses rather than celebrating them during Black History Month.

“My point was that without both, some students might assume the authors are white,” says Fecho, Professor of English Education. “But I didn’t ask for people’s thoughts.” Instead, he says, he should have induced “wobble,” or just enough “disequilibrium” to prompt reflection.

“We all belong to multiple cultures that include gender, sexual preference, class, interests in sports or the arts, and more. Culturally responsive pedagogy should respond to them all.”

— Bob Fecho, Professor of English Education

Teaching itself is learned by wobble, argues Fecho, who taught English for 24 years in a big North Philadelphia high school. In books such as “Is This English?” Race, Language, and Culture in the Classroom and Teaching for the Students: Habits of Heart, Mind, and Practice in the Engaged Classroom (both published by Teachers College Press), he describes striving for classes to “unpack texts for themselves” and “individually and collectively make meaning.”

Fecho once despaired of student essays about literature as either empty or convoluted. But influenced by educator Louise Rosenblatt, he came to view reading as a “transaction” with “text” co-created by each reader’s experiences and ideas: “If I wanted my students to take greater interest in their writing, I had to take greater interest in my students.”

In the early 1990s, Philadelphia allowed its schools to divide into autonomous learning communities. Fecho’s group structured curricula around “essential questions” — for example, following clashes between Brooklyn’s blacks and Jews, the issue of how communities deal with change. The readings mixed journalism, fiction, poetry — whatever was germane.

“If you create a unit on dinosaurs, only some students will be interested,” Fecho explains. “But if you ask, ‘What does studying dinosaurs tell us about life today?’ they’ll see the cohesiveness of reading, writing, listening, speaking. They’ll learn about thinking and ethics” — a must for dis-affected teens who “could make money selling drugs and didn’t expect to live long.”

More recently, still interested in personal meaning-making, Fecho has taught the theories of the late Mikhail Bakhtin, who argued that “to make an utterance means to appropriate the words of others and populate them with one’s own intention.”

For Fecho, true “dialogic teaching” entails understanding the many “cultures” that shape students’ responses to others’ utterances and their intersection in the “cultural contact zone” of the classroom. “In this country, we conflate ‘culture’ with ‘race’ — but we all belong to multiple cultures that include gender, sexual preference, class, interests in sports or the arts, and more. Culturally responsive pedagogy should respond to them all.”

Focusing on Racism, Not Race

“I put my hope in the generation coming of age. Like student activists of the 60s, they have a strong sense of justice, the power of education and the capacity to make change.”

— Sonya Douglass Horsford, Associate Professor of Education Leadership

“The board was local and everything was community-based,” she recalls. “But then came charters funded by for-profit organizations and managed by companies from out of state. They drained state resources.”

For Horsford, Associate Professor of Education Leadership, the charter movement’s evolution exemplifies “the irony and paradox” of expecting U.S. schools to serve as “an equalizing force in a country founded on race and class inequality.” Her scholarship explores how American education policy for the past six decades reflects a racial caste system that invokes “color-blindness” and “meritocracy.” Education researchers are complicit, she argues, when they focus on dissimilarity and diversity while ignoring context — poverty, prejudice, unequal opportunity — and racism’s impact on schools.

In her 2011 book Learning in a Burning House: Educational Inequality, Ideology, and (Dis)Integration, Horsford interviews retired black school superintendents in whose districts, in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s words, the races achieved “physical proximity, but not spiritual affinity.” They contrast the mass firing of black educators occasioned by desegregation, and the toll exacted on black students by practices such as busing, with the tightly knit all-black school they attended, where caring adults reinforced high expectations.

Though dismayed by the current political climate, Horsford sees opportunities to “reframe discussions of race and racism from individual attitudes and acts of prejudice and discrimination toward an examination of the structural, institutional and administrative policies, processes and practices that maintain and reproduce inequities in schools and school systems.

“I put my hope in the generation coming of age. Like student activists of the 60s, they have a strong sense of justice, the power of education and the capacity to make change.”

Listening for Language Development

“The whole island is four by 11 miles but encompasses 14 languages,” recalls Hammer, Professor of Communication Sciences & Disorders. “You couldn’t find much about it online, so instead of acting as the expert, I learned about the culture from the parents of children I was treating. Then I worked from their perspective.”

“Assessing preschoolers’ literacy development “would help us identify problems and intervene when we can really make a difference.”

— Carol Scheffner Hammer, Professor of Communication Sciences & Disorders

Today Hammer applies that approach in two federally funded projects. In one, she is developing the first tool for gauging literacy development in preschool-aged bilingual (English/Spanish) children. In the other, she is co-developing online training for parents of children with language disorders.

Why assess literacy in preschool, when children aren’t reading? Because that’s when kids develop an important precursor skill called phonological awareness — the ability to hear and manipulate words and parts of words.

“An assessment given at this age would help us identify problems and intervene when we can really make a difference,” says Hammer.

Teachers would use an app to show children groups of pictures and, for example, ask them (in both languages) to identify the image that rhymes with a particular word or sound. Each child’s score would be compared against norms that Hammer and her team are establishing through a study of 900 bilingual children.

“The norms will tell us where a child stands on a continuum and where to start intervention, if needed,” Hammer says.

The coaching program for parents of preschoolers with established language disorders also is aimed at predominantly low-income, minority families. Parents would learn language improvement techniques they can embed in children’s everyday activities through an app.

“I came to TC because our program is unique in its focus on diversity, bilingualism and multiculturalism,” Hammer says. “We do intervention research aimed at making a difference in people’s lives.”

The New Civics

“Young people may feel disconnected from and skeptical about politics, but they’re also very involved in online spaces.”

— Ioana Literat, Assistant Professor of Communication, Media & Learning Technology Design

“Children’s books about the Internet are mostly about bullying, piracy and addiction,” says Literat. “I wanted kids to know they can use the Internet to connect with peers and find safe spaces to experiment with creativity.”

Literat grew up in post-revolution Romania’s lingering authoritarian climate. She left via a scholarship to the United World College in Canada, studied at the University of Southern California with transmedia guru Henry Jenkins and worked in India, field-coordinating a digital storytelling program in public schools. Currently, she’s exploring the “political socialization” of youth online.

“The attitudes cultivated in youth about civic life leave a lasting impression. Young people may feel disconnected from and skeptical about politics, but they’re also very involved in online spaces. There’s much to learn in revamping civic education.”

Now Literat and Neta Kligler-Vilenchik of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem are analyzing youth postings to sites such as Pixilart, Scratch, Know Your Meme, HITRECORD and Archive of Our Own immediately after the 2016 presidential election. They’ve found hundreds of election-related games, memes, fan fiction, digital art, collaborative animations and other creations expressing young people’s political stances and concerns.

“In times of crisis, youth don’t have much support in terms of what to believe,” Literat says. “The number one fear is of intolerance and racism — ‘What will happen to me and my friends?’ It breaks my heart, but it’s beautiful that young people have safe spaces to express themselves, communicate and grow as citizens. I’m not a technological determinist by any means, but there’s something very special about the moment we’re living in.”

First Editions: TC’s Faculty in Print

Perspectives From Schools Around the World

The relationship of elite schools to their British colonial pasts. Post-Fidel Cuban “socialist citizenship education.” A grassroots teacher network in Finland. Those are among the case studies in Educating for the 21st Century: Perspectives, Policies and Practices from Around the World (Springer 2016), edited by Suzanne Choo (Ph.D. ’12), Deb Sawch (Ed.D. ’13), Alison Villanueva (Ph.D. ’13) and TC faculty member Ruth Vinz.

As students, Choo, Sawch and Villanueva, guided by Vinz, convened educators and researchers from around the world. Their book illuminates how countries and systems enact school change. For example, Finland’s Innokas Network, which supports teaching and learning of core 21st-century capacities, emphasizes peer-led teaching, parent involvement and teacher ownership.

Choo, Sawch, Villanueva and Caroline Chan of Singapore’s Ministry of Education describe a top Connecticut district that (with their help) embraced global education at scale — including a unit on “issues of the voiceless,” anchored by A Tale of Two Cities, and a math course on solving real-world problems.

“It speaks to the power of TC to help incubate big ideas,” Sawch says. — Joe Levine

Prescription For a Fragile Planet

How do you teach young people to identify as members of a global community? Through an ethos, not a curriculum, argues William Gaudelli.

In practice, Global Citizenship Education (GCE) entails instilling “mindfulness about how the world is present in all materials and relational interactions,” writes Gaudelli, Associate Professor of Social Studies & Education, in Global Citizenship Education: Everyday Transcendence (Routledge 2016). He eschews a single vision of GCE, describing how schools in Bangkok and New York City encourage students to understand their relationship to the world through the lens of their respective societies. But he does urge “a common understanding of shared humanity,” and “addressing social problems through engaged public participation.”

Getting there requires “a wider, more-encompassing perspective on the human condition” coupled with “openness to the plurality of people and their environs.” That’s a tall order, but in a world where communities on opposite side of the planet are increasingly economically interdependent, Gaudelli makes a powerful case that discovering what unites rather than divides us should no longer be an elective option. — Mark Frankel

Guest Faculty Essay

Begin With All Iinteractions Overtones

There could hardly be a more auspicious time to renew our commitment to the deep values in education. Consider the intensifying pressure on educational systems to transform themselves into mere appendages of the economy; the nation’s fractured, polarized public discourse; the persistence of discrimination; the ongoing assault on truth, the reality of fact and scientific findings; the increasing pressures exerted by overpopulation and climate change; and the stark fears these forces engender. Under such conditions, educators across the system must reaffirm their commitment to those they serve and the aims they strive to realize.

“All education leaves its mark, however indiscernible at first glance, on how people think, act, perceive, judge and communicate.”

— David T. Hansen, John L. & Sue Ann Weinberg Professor in the Historical & Philosophical Foundations of Education

Part of this reaffirmation is awareness that all education, especially in a purported democracy, has civic overtones. All education leaves its mark, however indiscernible at first glance, on how people think, act, perceive, judge and communicate. Those ways leave their imprint — again, however seemingly microscopic — on the people with whom a person dwells and interacts. We are always already influencing the larger human ethos.

Civic education can be understood as a name, or term of art, for bringing people into awareness of their dynamic place in society: a mindfulness that the nature and quality of their society depends upon their conduct with others. Every person has a measure of civic agency simply by virtue of participating in daily life. To be sure, we require institutions and policies that can level the playing field, such that each person’s agency begins to “count” as much as another’s. But while the infinitely challenging labor of creating such structures goes on, life on the ground can be deeply enriched and revitalized through civic education and the critical mindfulness it promotes.

This task requires no special program. Rather, this spirit begins with educators, and it constitutes a great calling in our historical moment. — David T. Hansen

Published Thursday, Jun 15, 2017