A new public school in Akron is making headlines primarily because of its underwriting and sponsorship by the basketball mega-star LeBron James. Yet educators and parents may be even more enthused because James’ creation is a “community school,” offering support services such as free meals, on-site psychologists and counseling, job-placement services and GED programs for families.

That’s no isolated reaction. A new survey from The Public Matters project at Teachers College, Columbia University indicates that the appetite for community schools is strong. The national, online survey of about 3,000 adults, released August 10th, shows that a majority of Americans approve of schools that offer integrated educational, social, health and community services to students and families.

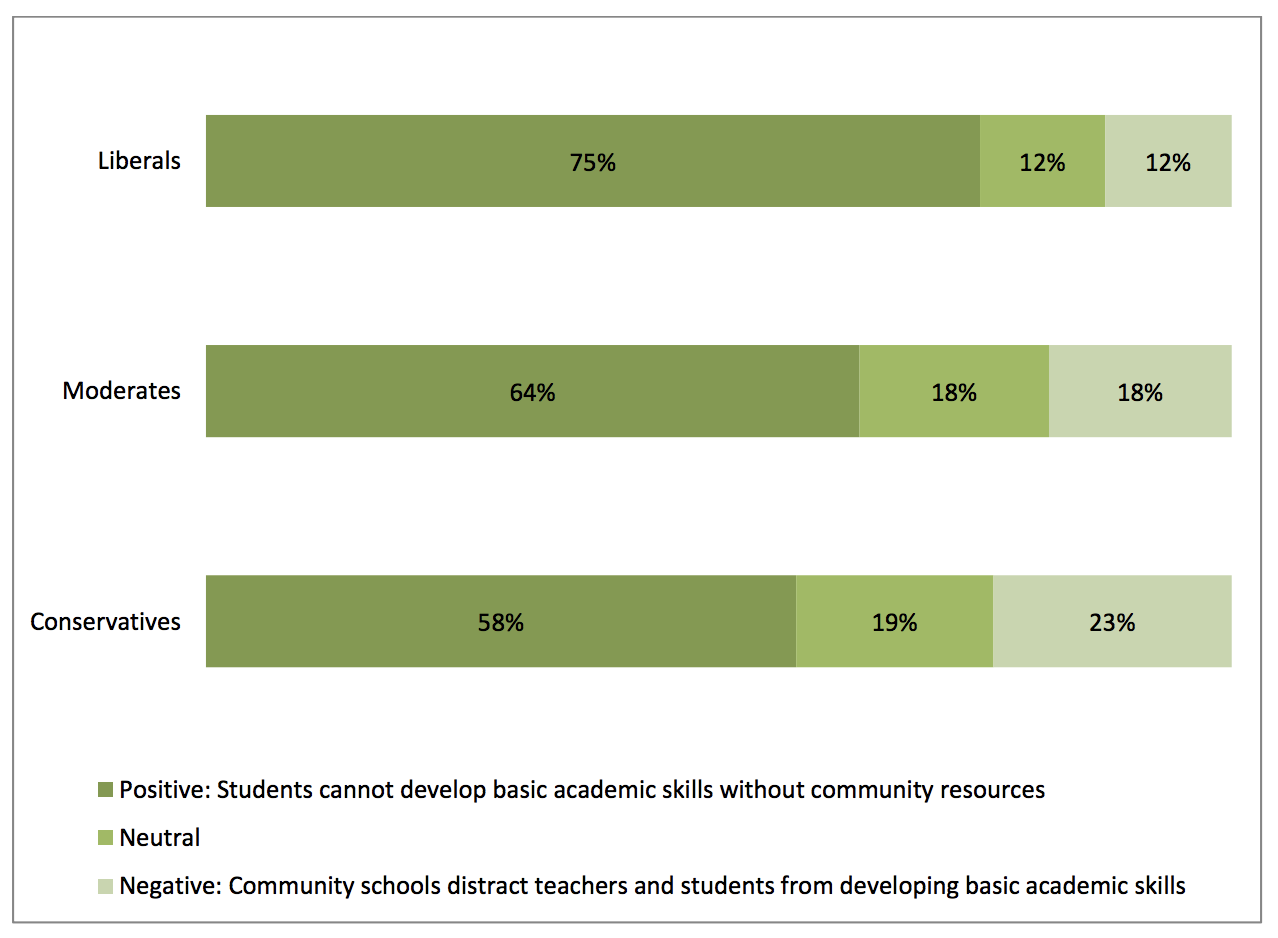

Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of survey respondents said they supported this statement: “Students cannot develop basic academic skills without community resources, health and social services.” Eighteen percent were critical of community schools and supported this alternative statement: “Community schools distract teachers and students from the mission of developing basic academic skills,” while 17 percent were neutral on the question.

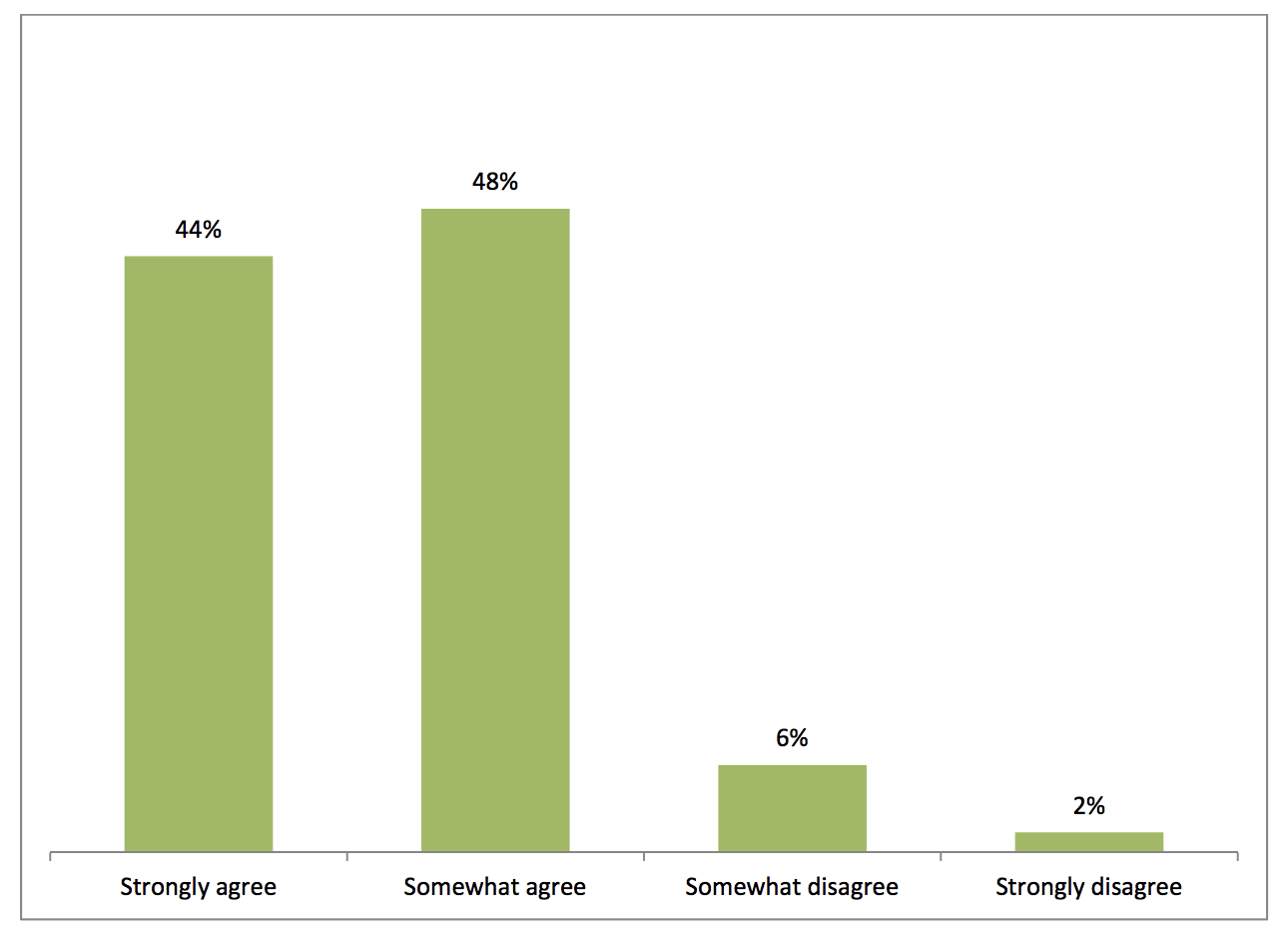

Nearly all (92 percent) respondents said they agree that “teachers should use an approach that looks beyond a student’s current academic performance to all aspects of a person’s well-being,” including 44 percent who indicated they “strongly agree” and 48 percent saying they “somewhat agree.” Eight percent said they “somewhat disagree,” and 2 percent “strongly disagree.”

Community schools have existed in the United States since the early 20th century. However, for more than the past two decades, public education has de-emphasized the holistic approach espoused by community schools and focused instead on academic instruction and testing.

Previous studies have shown that Americans are losing interest in reforms that draw primarily on test-based accountability, said Oren Pizmony-Levy, Assistant Professor of International and Comparative Education. “Taken together, the public is clearly signaling to policy makers that it’s time to try new types of reforms that invest not only in improving instruction and curriculum, but also invest in the whole child and families.”

Indeed, in answering a different question about agreement with the general principles of community schools, an overwhelming 92 percent of respondents said they agree that teachers should look “beyond a student’s current academic performance to all aspects of a person’s well-being” (Figure 4.1).

The survey, co-authored by Pizmony-Levy and TC colleagues Aaron Pallas, Arthur I. Gates Professor of Sociology and Education, and Nancy Streim, Associate Vice President for School and Community Partnerships, defines a community school as one that “creates partnerships between the school and community resources that integrate academics, family support, health and social services to promote student development.” Unlike charter schools, community schools are run, either jointly or entirely, by the local school district.

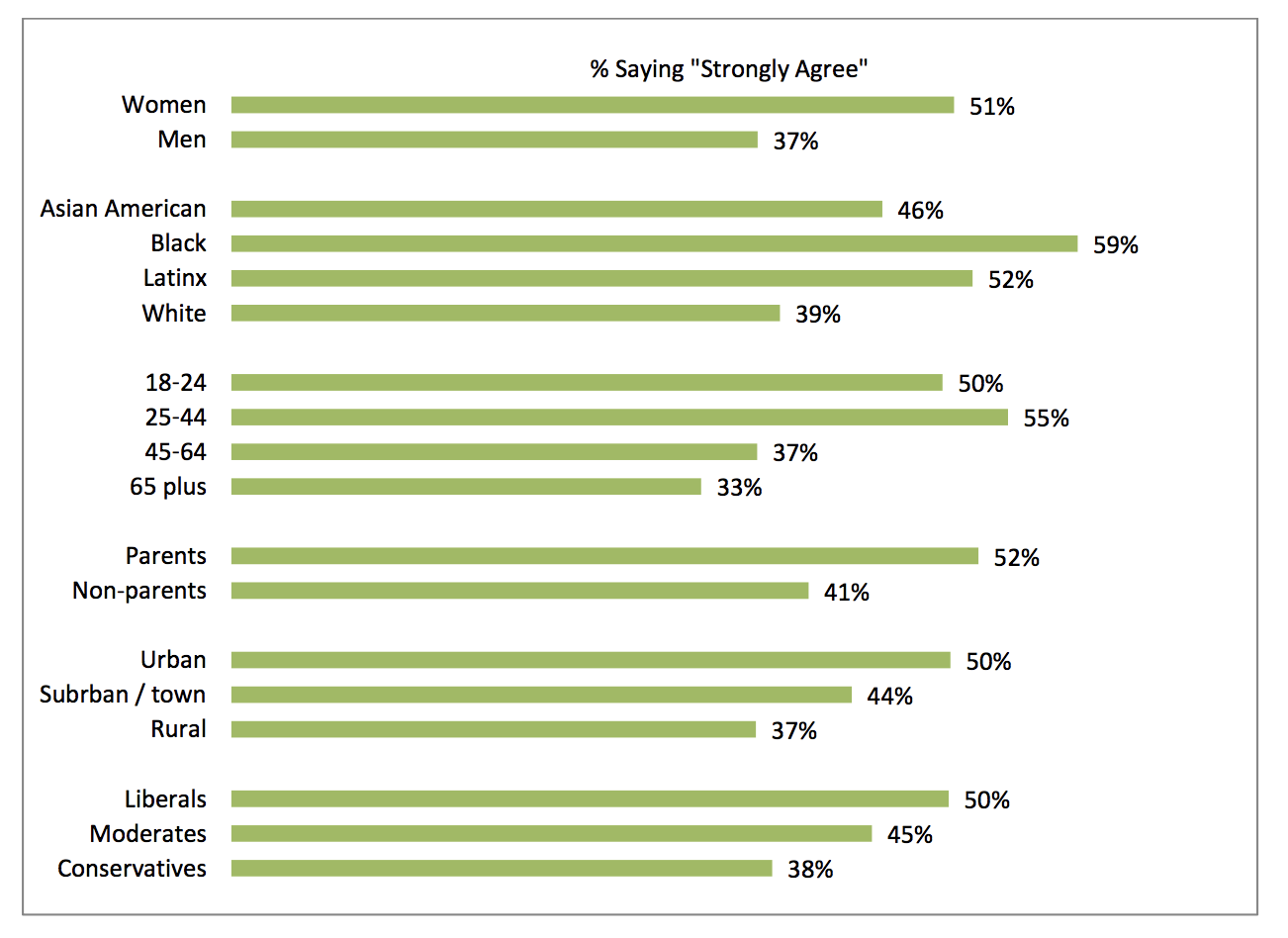

More women, blacks, young adults aged 25-44, parents, urban dwellers and liberals strongly supported teaching that “looks beyond a student’s current academic performance.” Men, whites, adults 65 or older, non-parents, rural residents, and conservatives expressed less support.

After reading that definition, respondents were asked how much, if anything, they had heard about community schools. Two-thirds of respondents (67 percent) indicated they had, while one-third (33 percent) said they had not.

“I am pleasantly surprised that so many people knew about community schools,” Streim said. “That suggests that the idea of schools as community hubs to address the needs of children and families is becoming more commonly understood as a promising approach for promoting school success.”

Streim is an expert in community schools, having led the creation, with Teachers College’s former President Susan H. Fuhrman, of the Teachers College Community School, a public PreK-8 school in Harlem jointly run by TC and the New York City Department of Education. Teachers College’s legacy with community schools goes back to 1902, when the College co-founded the Speyer School in Harlem.

“The most interesting part” about the study, Streim said, “is what people think schools should be doing. Community schools are just one approach, but there’s obviously widespread support—almost unanimous support—for taking into account all of kids’ needs, talents and differences.”

Among respondents who had heard about the community school model, more women than men had a more positive view of them. Among racial and ethnic groups, Asian Americans expressed the most positive views, followed by Blacks and Latinx respondents, and whites were the least positive. Parents of school-aged children were more positive than non-parents, and urban dwellers were more positive than suburban or rural residents.

Among respondents who said they had heard about the community school model, 75 percent of liberals gave a positive rating to the the statement, “Students cannot develop basic academic skills without community resources,” while 58 percent of conservatives and 64 percent of moderates strongly agreed.

Support for the community school concept of “teaching to the whole child” was higher among women, people of color, younger adults, parents of school-age children and urban dwellers (Figure 4.2). Fifty-eight percent of self-described conservatives indicated support for community schools, compared with 75 percent of liberals and 64 percent of moderates (Figure 3.4).

Streim said more research needs to be done to determine “what makes community schools work, and what the relationship is between all these services and academic outcomes. That’s challenging, because they aren’t necessarily causal relations.” Streim and her colleagues are studying the relationship of community school services to academic outcomes. They should have results this fall, she said.

Funded by the Teachers College Provost Investment Fund and launched earlier this year, The Public Matters project conducts, analyzes and releases periodic public opinion surveys on topics and issues related to education, psychology and health, the three areas of expertise, research and teaching at Teachers College.