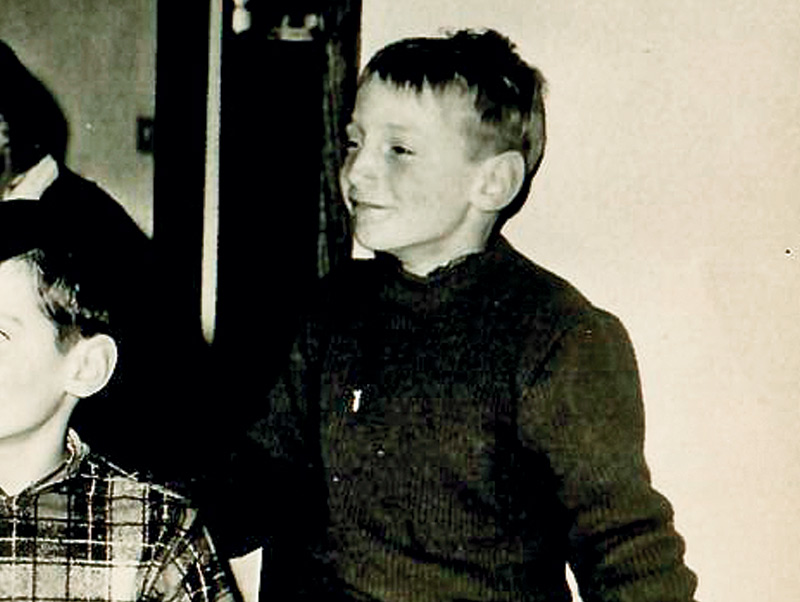

After finishing high school in 1968, Tom Bailey traveled across North Africa, hitching rides and sleeping on people’s floors. Back home he was a sanitation worker, a cab driver and an apprentice welder, learning alongside recent Vietnam veterans. He became a husband and father. He was four years older than most of his fellow freshman when – somewhat to his own surprise – he enrolled at Harvard to study economics.

“I realized that, unlike many of the people I’d worked with, I was lucky to have parents who could afford to pay my tuition,” he says. “But I was also fortunate to have had experiences that gave me an appreciation for others’ lives and points of view. Those experiences could have derailed me if I’d had less margin for error.”

For Bailey, that conundrum is central to his new role as Teachers College’s 11th president – a job he took in July after 27 years on the College’s faculty.

“How do we make higher education, with its consideration of broader ideas and life questions, both accessible and navigable to those without the time and means to devote four years to reading books and writing papers?” he mused one day this past summer. “How can we ensure that it has the richness that comes from detours – intellectual ones, if not in terms of time and place – that I was lucky enough to be able to take?”

In a society where the relationship between education and employment is both taken for granted and hotly debated, Bailey is hardly alone in mulling such questions. But for the past 22 years, as the founding director of TC’s Community College Research Center (CCRC), he’s been a driving force behind a quietly unfolding national success story: the slow but steady shift at community colleges from providing education access, to working more explicitly to ensure that students graduate and gain the knowledge and skills to succeed in work and life. (Bailey stepped down this summer as CCRC director, succeeded by Thomas Brock.)

“There’s a huge movement to redesign community colleges, and the CCRC, under Tom, has created its language and framework,” says Kendall Guthrie, Chief Learning Officer at the College Futures Foundation and previously the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s funding officer for CCRC. “And now Tom’s book – the blueprint for taking that movement to the next level – is on the shelf of every community college president and every foundation president who funds work on community colleges.”

“Tom’s book” is Redesigning America’s Community Colleges: A Clearer Path to Student Success (Harvard University Press 2015), coauthored with CCRC researchers Shanna Smith Jaggars and Davis Jenkins, which lays out a comprehensive approach – called, fittingly, Guided Pathways – for helping students plan and complete their studies with both intellectual and career goals in mind.

“Guided Pathways is the right image for reeducating people for the workplace,” says Jesse Ausubel, a former Alfred P. Sloan Foundation program officer (now at Rockefeller University) who first proposed creating CCRC. “America tends to be satisfied with equality of opportunity, but people without jobs need counseling and guidance, whether they're from a 400-year-old American family or just crossed the border.”

There are plenty of reasons why Bailey was, in the words of TC Board Chair Bill Rueckert, “the consensus choice” to lead the nation’s best-known college of education. Authorities like former Second Lady Jill Biden (herself a longtime community college educator) have credited him and CCRC with establishing a culture of evidence and putting community colleges on the country’s education agenda.

He’s been funded by Gates, Sloan, Lumina, Mellon, Hewlett, Ford and many other foundations.

He’s directed three national centers funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences and chaired an Obama administration commission on developing new outcome measures for community college students. (Many of those proposed measures were subsequently implemented by the Department of Education.) He’s promoted real-world change by convening diverse thinkers, combining sophisticated long-term clinical studies with old-fashioned field observation, and partnering with front-line practitioners to create strategies that incorporate their experiences and ideas.

Yet, ultimately, it may be Bailey’s concern for educating people from all backgrounds – and his openness to “others’ lives and points of view” – that make him an inspired choice.

“This is a moment when we really need to step back and rethink how to do things in education,” says Bailey’s co-author, Davis Jenkins. “What are our goals, and what does that imply for how we structure schools and experiences? Tom has spent years thinking about those questions and listening to the ideas and needs of other stakeholders. So I think his knowledge and scholarship are going to play out well for TC.”

Consensus Builder

One thing people quickly discover about Bailey is his natural curiosity.

Whether the topic is education pol- icy or summer vacations, he asks questions – and actually listens to the answers.

Quakers value consensus. The idea that you want to listen to what other people say, and try to incorporate their views and interests into your decision, is a value I try to live by.”

—Tom Bailey

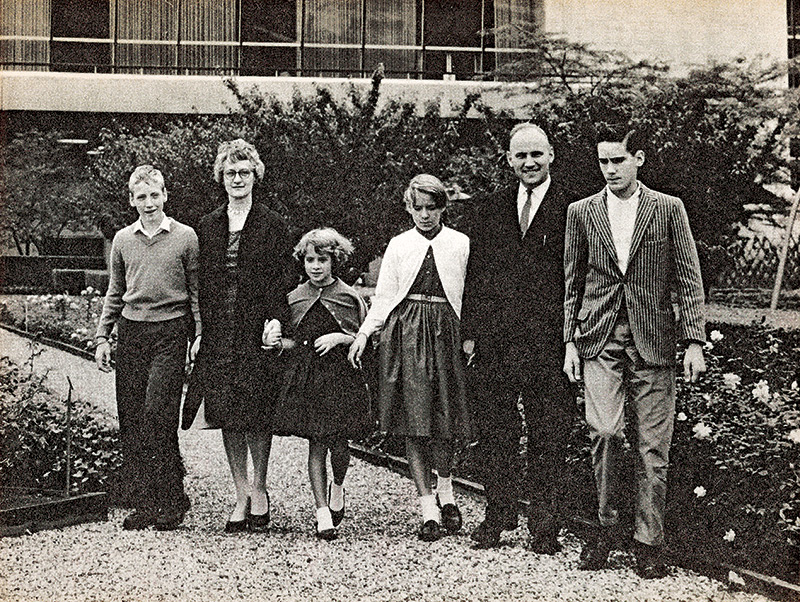

That purposeful inquisitiveness is more than mere politeness. Bailey’s parents were both nationally active Quakers: His father was a lobbyist for the Friends Committee on National Legislation and later directed a set of “conferences for diplomats” for the American Friends Service Committee in Switzerland, where Bailey attended French elementary school. The elder Bailey then spent 20 years working for UNICEF. Bailey’s mother served on the boards of both the Quaker U.N. Program and the Quaker study center Pendle Hill outside of Philadelphia, and her father was President of Quaker-founded Guilford College in North Carolina. While family discussions were often about poverty, peace and other social issues, Bailey, who is no longer a practicing Quaker, was influenced as much by the tone as by the content.

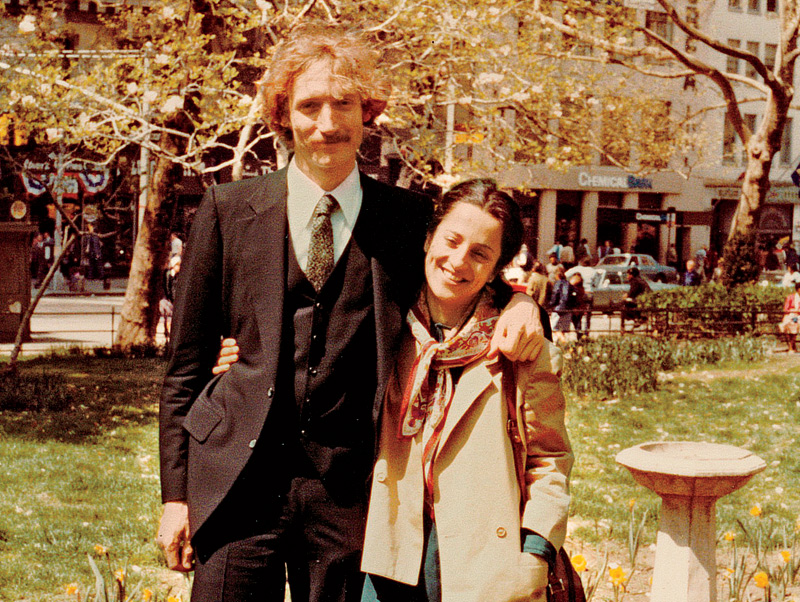

“Quakers value consensus,” he says. “The idea that you want to listen to what other people say, and try to incorporate their views and interests into your decision, is a value I try to live by.” He credits his wife, Carmenza Gallo, with helping him do that. She is now a docent at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art after having spent 25 years as a sociology professor at CUNY’s Queens College, focused on political instability in Latin America.

“A crucial foundation of our marriage has been a lively intellectual exchange on culture, art, literature, world events and politics,” Bailey says. “Carmenza has not been reluctant to challenge any argument – to say, ‘what, you think that?’ – and has convinced me to amend many conclusions. She has also given me a different and insightful perspective on people, helping me to understand them and thereby to be a better friend and a more effective colleague and leader. I’m grateful to her for many of the emails I haven’t sent.”

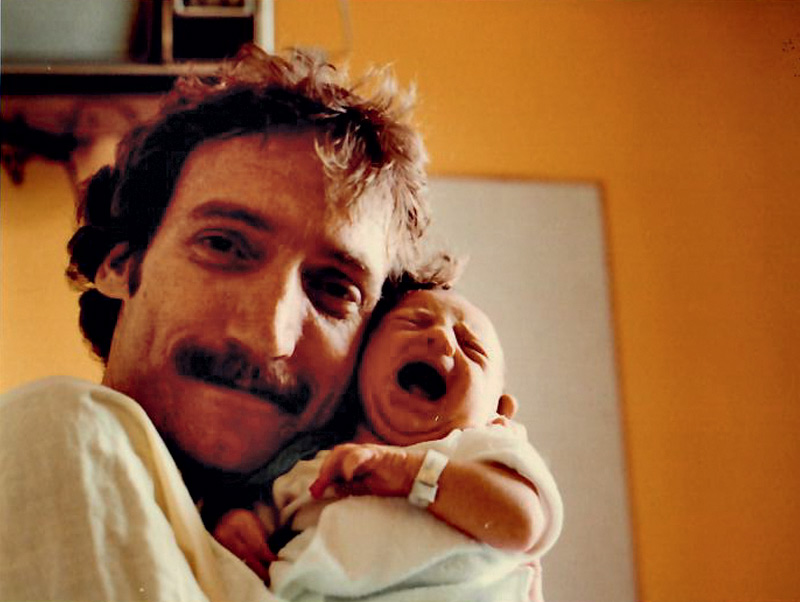

He also listens to his two daughters – Erika, the Head of Voice and Speech at Harvard’s American Repertory Theater, and Daniela, an alumna of TC’s Klingenstein Center who is a social sciences teacher and class dean at the National Cathedral School in Washington, D.C. “I have learned a great deal from their experience as teachers and leaders.”

Changing the Game

Bailey’s listening skills have clearly shaped his approach to research, beginning with his earliest work as a labor economist.

In the mid-1980s, he set out to learn what it would take for U.S. manufacturers to adopt “flexible specialization” – a term popularized by his MIT doctoral thesis adviser, Michael Piore. An important stream of Piore’s thinking emerged from a movement away from the mass production ethos defined by Henry Ford’s promise that “a customer can have a car painted any color he wants, so long as it is black,” toward production that could respond to an increasingly varied range of customer demands. In research that Jesse Ausubel calls “almost anthropological,” Bailey spent several years observing production and interviewing workers, managers and line supervisors at apparel and textile manufacturing plants in states from New York to Alabama, and North Dakota to Arizona.

IVORY LEAGUE Bailey has a taste for Chopin – and an appreciation for art, culture and a well-rounded education.

In his publications, Bailey describes not only the minutiae of how work was organized and how workers carried it out but also the zeitgeist of an entire industry and era. “Managers believe that the industry’s competitiveness depends on their ability to ‘engineer’ the work process by breaking down each process into minute tasks that take only seconds to perform,” he wrote in 1993 in Industrial Relations, soon after joining TC’s faculty. “Apparel makers seek low-wage workers, with virtually no educational requirements for most operations.” Variety and change were the enemy: “The industry’s past success was based on the production of low-cost, mass produced goods in which styles changed slowly… for example, by 1979, Levi’s best-selling 501 jeans had received only minor modifications since it was first introduced in the early 1880s.”

As for encouraging employee adaptation, “In many sectors of the industry, white managers supervise immigrant or native minority workers, and in the vast majority of apparel plants, the managers are men, the operators, women. These differences may explain management’s unwillingness to share power and authority.”

Everyone knew change was needed: The market share of imports had soared in recent years. But the managers Bailey interviewed wanted to deploy new technologies and automation to further remove the human element. Bailey argued that this was dead wrong – that technology was only as smart as the people operating it. Employees needed to become more skilled, knowledgeable and strategically involved in production – and that required education. Bailey and his colleague Sue E. Berryman saw many parallels between the type of work organization that he was criticizing and the organization of the typical school and classroom. As they wrote in their 1992 book, The Double Helix of Education and the Economy, “traditional schooling, especially its pedagogy, is poorly organized for learning, whatever the economic environment students find themselves in.” American colleges rewarded individual rather than group effort; they were degree- rather than skill-oriented; they tended to divorce knowledge from practice; and they were expensive and time-consuming to attend.

The reformed workplace and the reformed school had much to learn from each other. Work-based learning is “narrative, dramatic and personal,” whereas school-based learning, with its emphasis on scientific proof, is “decontextualized, propositional – no fun!” Bailey wrote in another book, Working Knowledge, co-authored with Katherine L. Hughes and David Thornton Moore.

Moreover, the workplace itself, if organized appropriately, could be an effective classroom. “We were interested in applied education – this idea that people actually learned better in the context of something that they were interested in,” Bailey recalls. “We argued that vocational education, even in high school, didn’t have to be a dumping ground. That, if done right – if you learned math by, say, building a bridge – it could actually be, for many students, a better way to teach academic skills.”

Yet Bailey has resisted the distinction between vocational education (or career and technical education, as it is referred to now) and so-called academic education. “I believe strongly in a liberal arts education, which provides critical skills that employers overwhelmingly want,” he says. And so do students. “Certainly people go to college for the love of learning. But when I ask groups, ‘How many of you went to college without thinking it would get you a better job?’, no one raises a hand. We’re all looking for work. We all want a career.”

When I ask groups, ‘How many of you went to college without thinking it would get you a better job?’, no one raises a hand. We’re all looking for work. We all want a career.”

—Tom Bailey

It was Ausubel, at Sloan, who first argued for a center that would focus on community colleges. These open-access institutions prepared students to transfer to four-year schools and granted two-year associate’s degrees and even shorter-term certificates centered on specific skills. TC, which had prepared top community college presidents during the ’60s and ’70s, was the obvious place to house such a center. And Bailey was the obvious person to lead it. Noting his ability to relate well to different kinds of people, Ausubel says, “He connects with folks who aren’t credentialed or long on book learning. He doesn’t give speeches – he listens. And he has a great sense of humor.”

Field Partner

Bailey would need all of those assets in working with community colleges to help them understand and implement reforms needed to improve student outcomes. Compared to other sectors of the higher education system, community colleges accept students who face the greatest barriers yet receive the fewest resources – and their faculty and administrators might understandably have bristled at advice from a bunch of outsiders dropping in from an Ivy League university that would turn away most of their students.

Financial incentives also stood in the way of reform. “When we started, I would say that most community college presidents could not have told you their graduation rate,” Bailey recalls. “College presidents wanted their students to succeed, but most colleges in the public sector are paid on enrollments, not completions. It didn’t matter if you replaced most of your first-year class every year and only had a few second-year students – if your enrollment went up, you were paid more.” Indeed, no consistent and comparable measure of completion existed until the early 21st century.

In 2004, Bailey and CCRC, with other organizations, created Achieving the Dream, a national intervention, initially funded by the Lumina Foundation for Education, that prompted community colleges to “face the data” of their own graduation rates, assess their practices and track students’ performance to identify barriers to academic progress. In his signature style, Bailey and CCRC formed close working relationships with hundreds of practitioners at community colleges.

Achieving the Dream and other reform initiatives represented what came to be referred to as the completion agenda – innovations aimed at enabling more students to graduate. During the first decade of the new century, CCRC conducted many studies and evaluations of reforms that included:

Dual enrollment. A 2007 CCRC study in Florida and New York established that enabling high school students to enroll in college courses and earn college credit could improve their subsequent success in college.

Remedial education. CCRC’s landmark 2008 study found that fewer than half of community college students complete remedial courses intended to help them improve in math, reading and writing. These courses, in which institutions invest a collective $7 billion per year, more often demoralize students, costing them time and money for no credit. Other CCRC studies have shown that having students take remedial and college-level courses at the same time can be effective; that a quarter of remedial students would pass college courses with a B or higher; and that high school grade-point averages would be a better basis for remedial assignment than widely used standardized tests.

Financial aid. CCRC has demonstrated that the complexity of the federal financial aid form and the process of applying for Pell Grants is scaring off the neediest students.

But as the decade progressed, institutional graduation rates were not improving, despite documented successes with remediation or counseling. In addressing only a segment of the student’s college career, pilot projects were not changing overall institutional performance. Enter the Guided Pathways approach that Bailey, Jaggars and Jenkins lay out in Redesigning America’s Community Colleges. Like the “cocktail therapies” that turned AIDS into a treatable disease, Guided Pathways draws on all the strategies explored by Bailey and CCRC, and others, ranging from default but customizable course sequences to faculty monitoring that ensures students are really learning. The approach counters the “cafeteria-style” organization of most community colleges, whereby students must sort through an array of course offerings, programs and services. (Read more on Guided Pathways in the story “A Matter of Degree.”) As of spring 2018, about a fifth of the nation’s two-year institutions had committed to undertaking large-scale Guided Pathways reforms. California has appropriated $150 million for Guided Pathways reforms based explicitly on CCRC’s research. Guided Pathways requires extensive collaboration among faculty groups, staff, administrators and even other institutions. Given that hurdle and the extent of the changes required, CCRC researchers estimate that it will take five or six years to fully implement Guided Pathways and judge its long-term effects. Nevertheless, early-implementer colleges show significant improvements in measures such as the number of credits students complete during their first year and in a program of study.

The ideas in our book weren’t ones we dreamed up. We saw the good things community colleges were doing and reflected those things back … to put all the different elements together.”

—Tom Bailey

Bailey says that the development and implementation of the Guided Pathways model has been a collaboration between CCRC, other organizations and, of course, practitioners. “The ideas in our book weren’t ones we dreamed up,” he says. “We saw the good things some community colleges were doing and reflected them back in a framework that lets people put the different elements together.”

TC and the Future

“Putting together the elements” is also a frequent theme when Bailey talks about his new job. “TC is an incredible instrument for bettering education and all aspects of human development,” he says. “But to realize our potential, we need to be more than a federation of many excellent programs.”

First, as he sees it, the College must identify key issues it wants to address and find points of convergence. Then it must “draw on all our strengths, from our teaching programs to our work in psychology, health, nutrition and other areas,” to develop solutions on a mass scale.

He seems confident that the specifics will come. His immediate concern, this past summer, was how best to promote such collaborations.

“Going from focused projects to broader, comprehensive eff orts is difficult, and frankly the incentives in higher education go against that,” he said. “Search committees and tenure committees tend to reward people for solo publications, but the great need is to get people working together.”

To that end, he wants to encourage more multidisciplinary research. But he’s also concerned with collegiality. “Everyone who walks through these doors should feel their contributions and perspectives are valued – that they’re part of an intellectual community, working with people they trust and respect.”

In early September, as Bailey welcomed the fall incoming class, inclusivity was central to his message. “Our faculty includes top people in their fields, and they are also truly and fiercely dedicated to helping you achieve your goals,” he told students.

Success, he said, requires staying focused to take advantage of TC’s offerings. But it might also entail remaining open to surprises.

“TC is such a rich intellectual environment,” he said. “We’re doing fascinating work on a wide range of issues, and you never know how or when a new pathway or direction might open up.”

Afterward, he lingered with the students. After 27 years at TC, he was still learning. He shook hands and answered questions. And, of course, he listened.