A Black professor starts a summer enrichment program that brings promising students of color to campus to prepare them for college. The effort is so successful that it wins federal funding and, eventually, major backing from the Ford Foundation.

It’s a nice story, but not unheard of in this day and age.

Except that it didn’t happen in this day and age. The program was launched during the mid-1950s – in Mississippi, at what is now Jackson State University, a historically Black institution.

Of course, Jane Ellen McAllister, the program’s creator, was always way ahead of her time.

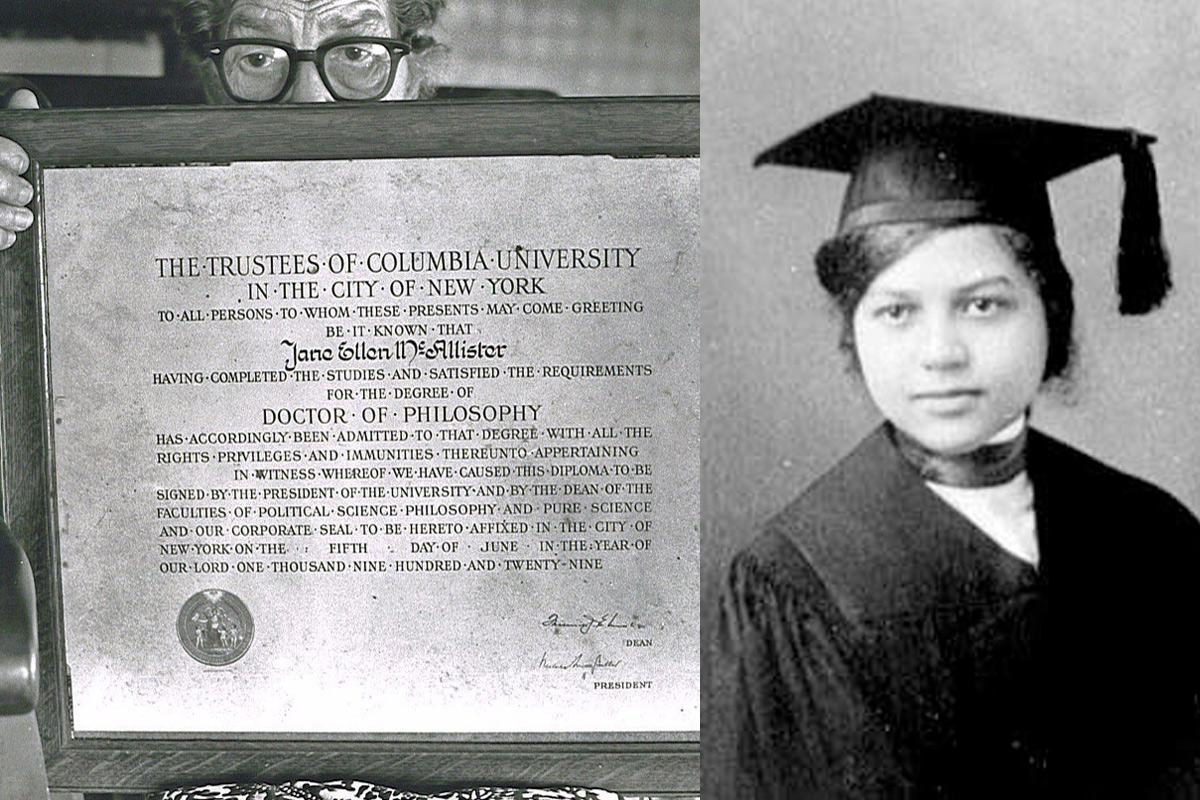

THE STARTING POINT Mabel Carney, TC Professor of Rural Education, wrote that “the real history of the study of American Negro education on the advanced level” began with McAllister’s TC thesis.” (Courtesy of Bettye Gardner)

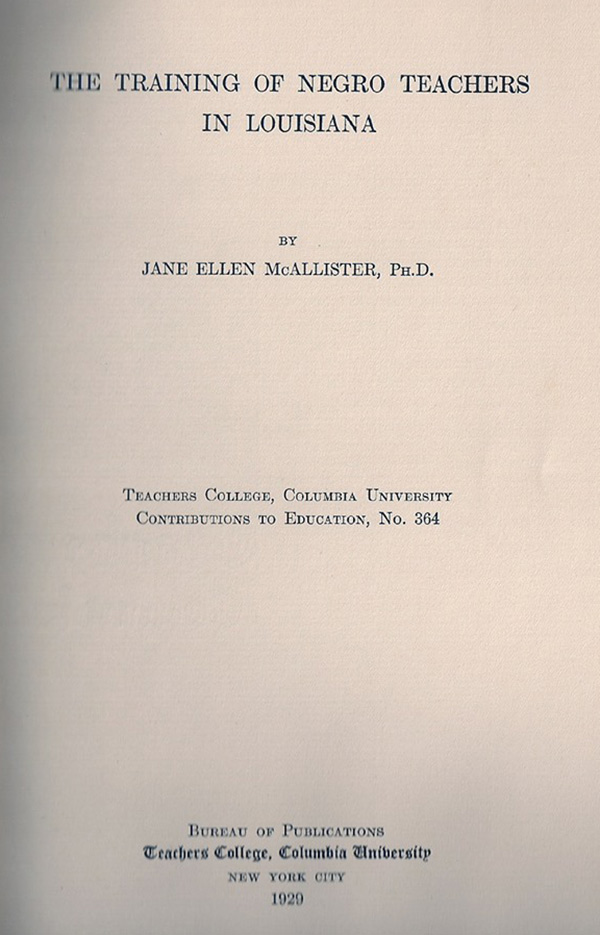

In the early 1920s, as a student at Teachers College, McAllister was the world’s first female African American doctoral candidate in Education. And when she completed the program in 1929, she became the nation’s first black woman to earn an Education Ph.D. Her Teachers College professor and advisor, Mabel Carney, subsequently wrote that “the real history of the study of American Negro education on the advanced level” began with McAllister’s TC thesis, titled “The Training of Negro Teachers in Louisiana.”

These remarkable achievements were only a prelude to a career devoted to improving teaching and furthering the prospects of people of color. Over the next 35 years, McAllister published scores of journal articles on teacher education. She taught and mentored generations of students at Jackson State, Virginia State College, Southern University, Fisk University and Miner Teachers College. And she launched many other innovative programs – including one in which students conducted telephone interviews with luminaries such as the journalist Edward R. Murrow and the classics scholar Moses Hadas. By the time McAllister died in 1996 at the age of 96, Jackson State had named a dormitory and a lecture series after her and the Mississippi Encyclopedia had enshrined her in its pages.

PROUD OF HER LEGACY

Now, on this coming Saturday, August 10th, Vicksburg, Mississippi, the historic Civil War city where McAllister was born and where she lived most of her life, will celebrate her life and work by unveiling a Mississippi state Historical Marker in front of her former home. As part of the festivities, a proclamation signed by TC President Thomas Bailey will be read aloud. It declares McAllister “a Teachers College hero who embodied the College’s values, beliefs and aspirations.”

For Bettye Gardner, McAllister’s cousin, and herself a historian and Professor Emerita at Coppin State University in Baltimore, the occasion is an essential part of preserving both McAllister’s own legacy and a rich part of African American and Southern history.

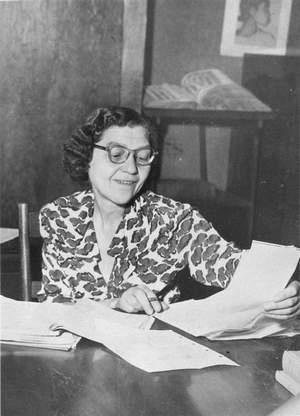

NEVER DAUNTED McAllister would likely be "disappointed" by public education in the post-segregation era, but she'd never give up the fight. (Photo: courtesy of Bettye Gardner)

“You know, people tend to have a monolithic sense of Mississippi – there’s the perception that it must have been the worst place to grow up as an African American – but Vicksburg has always been a progressive place,” says Gardner, whose mother was McAllister’s first cousin.

Certainly the city and its schools were segregated, but Vicksburg was unusual for not only having a Black high school, but one that was considered topflight. McAllister’s family was better off than many other Black families – her mother was a teacher and her father was a postal worker, and both were determined that she receive a good education. As a second grader, McAllister herself helped to teach first graders. She graduated from high school at age 15, and from Talladega College at age 19. Soon she was serving as a college instructor, teaching psychology, Latin and piano, before moving on to the University of Michigan to earn a master’s degree.

She was always interested in education for African Americans, because in that period, schools were not the best. One of her sayings was that ‘Poorly prepared teachers teach poorly prepared students to become poorly prepared teachers. And that’s why she ultimately chose to go to Teachers College.

—Bettye Gardner

“She was always interested in education for African Americans, because in that period, many Black public schools in the south were not the best,” Gardner says. “One of her sayings was that ‘Poorly prepared teachers teach poorly prepared students to become poorly prepared teachers. And that’s why she ultimately chose to go to Teachers College. Its reputation was so strong.”

McAllister was “aware of her place in history, but never boastful about it,” Gardner says. Rather “she knew how to draw on it to move things along.” At Jackson State, for example, she frequently picked up the phone to call the heads of the Ford Foundation and other funding organizations to ask for support of her innovative programs. These included a series that brought speakers to campus such as Ralph Bunche, Averill Harriman, Chester Bowles, Whitney Young and Roy Wilkins; a summer program for teachers from especially disadvantaged areas of Mississippi, which later morphed into an institute that served more than 1,200 teachers nationwide; a Statewide Superior and Talented Student Project that included black high schools; and a Self-Help Opportunity Program for unemployed high school dropouts.

AN EDUCATOR WAS IN THE HOUSE McAllister’s longtime home in Vicksburg, Mississippi, will soon have a marker in front of it. (Photo: Jennifer Baughn, MDAH)

“Those were different times, and the process of getting foundation grants was a little less rigid,” Gardner says. “But she never shied from doing what had to be done. And she was very shrewd in turning to foundations as a way of bypassing local, white-run legislative bodies and school boards that might have stood in her way. As a result, she took Jackson State to an entirely different level.”

McAllister was also a powerful influence in her own life, Gardner says. “She didn't have children, and I'd spend a lot of time at her house when I was little with her parents – my great aunt and uncle – chattering away.” Later, when Gardner and her friend were thinking about college, McAllister – again, years ahead of her time – insisted that she prepare for the standardized tests that would help determine her fate.

“I remember taking those practice tests to a timer at her house,” Gardner says.

In retirement, McAllister was known for taking care of stray animals and sick neighbors, and she once intervened to help keep the case of a Black teenager accused of a violent crime out of adult criminal court.

Living without bitterness is not easy; but education, not fighting, is the only way out of poverty, bias and ignorance.

—Jane Ellen McAllister

Gardner allows that if her cousin were alive today, she would very likely be “disappointed” by the failure of American public education to serve students of color in the post-segregation era. But McAllister would also be undaunted. As a biographical article about her puts it: “Dr. McAllister’s philosophy of life, developed in the stormy racial climate of her native South, is simply stated: ‘Living without bitterness is not easy; but education, not fighting, is the only way out of poverty, bias and ignorance.’”

—Joe Levine

View “My Mind to Me a Kingdom Is: The Legacy of Dr. Jane Ellen McAllister,” an online exhibition by the photographer David Rae Morris

Read about scholar and activist Marion Thompson Wright, the Teachers College graduate who in 1940 became the first African American woman in the United States to earn a Ph.D. in history.