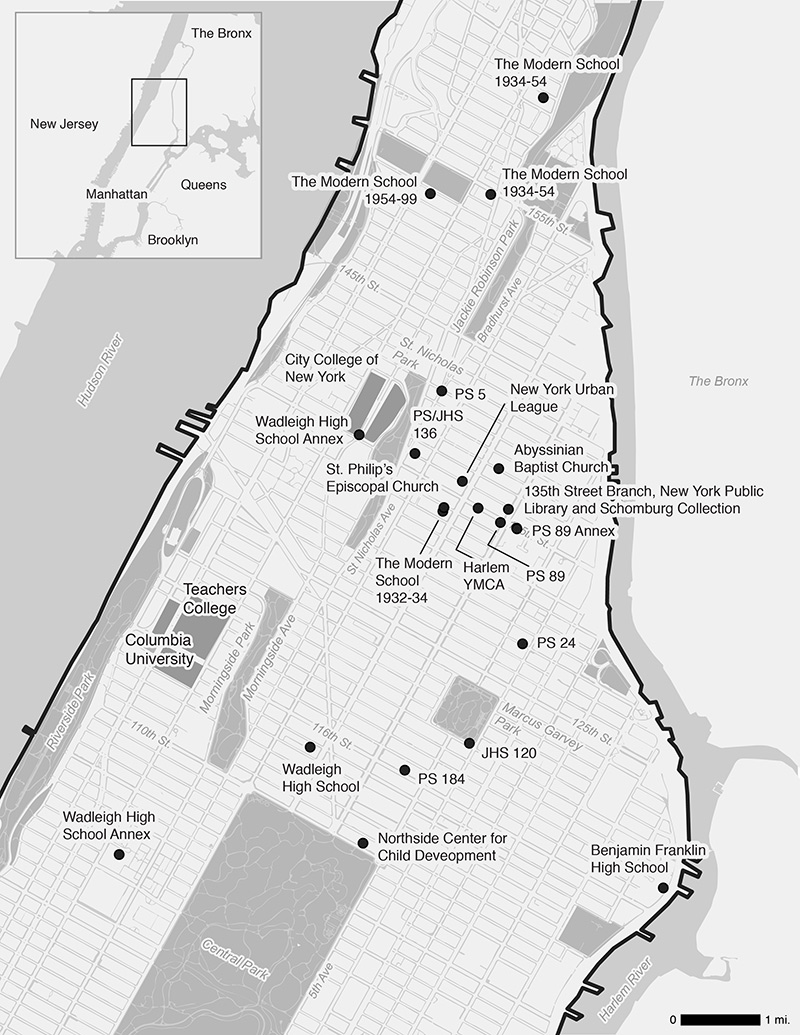

In 1811, a map drawn up by a white politician, a white surveyor, and a white lawyer created the New York City geography now known as Harlem. This “regimented grid of north–south avenues plotted 920 feet apart, crossed by east–west streets spaced 200 feet apart” would subsequently offer a “landscape of new opportunities” to a wave of black people coming from southern states, Africa and the West Indies,” write Ansley T. Erickson and Ernest Morrell in the introduction to their new edited volume, Educating Harlem: A Century of Schooling and Resistance in a Black Community. Yet the new arrivals would also find “well-worn pathways of racism, economic exploitation, and political oppression.”

[Educating Harlem is published by Columbia University Press. Through special arrangement with the publisher, an enhanced digital version designed by TC History & Education doctoral student Rachel Klepper and hosted by the Columbia Libraries, is available free of charge online.]

It’s no surprise that a book co-edited by Erickson, Associate Professor of History & Education Policy, would frame a history of Harlem through a 200-year-old city planning decision. Her previous book, the award-winning Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and Its Limits (Chicago, 2016), considers all the literal and figurative lines in the sand drawn by the white leaders of Nashville, Tennessee – a city often cited as a national exemplar of successful desegregation – to ensure that integration never went too far.

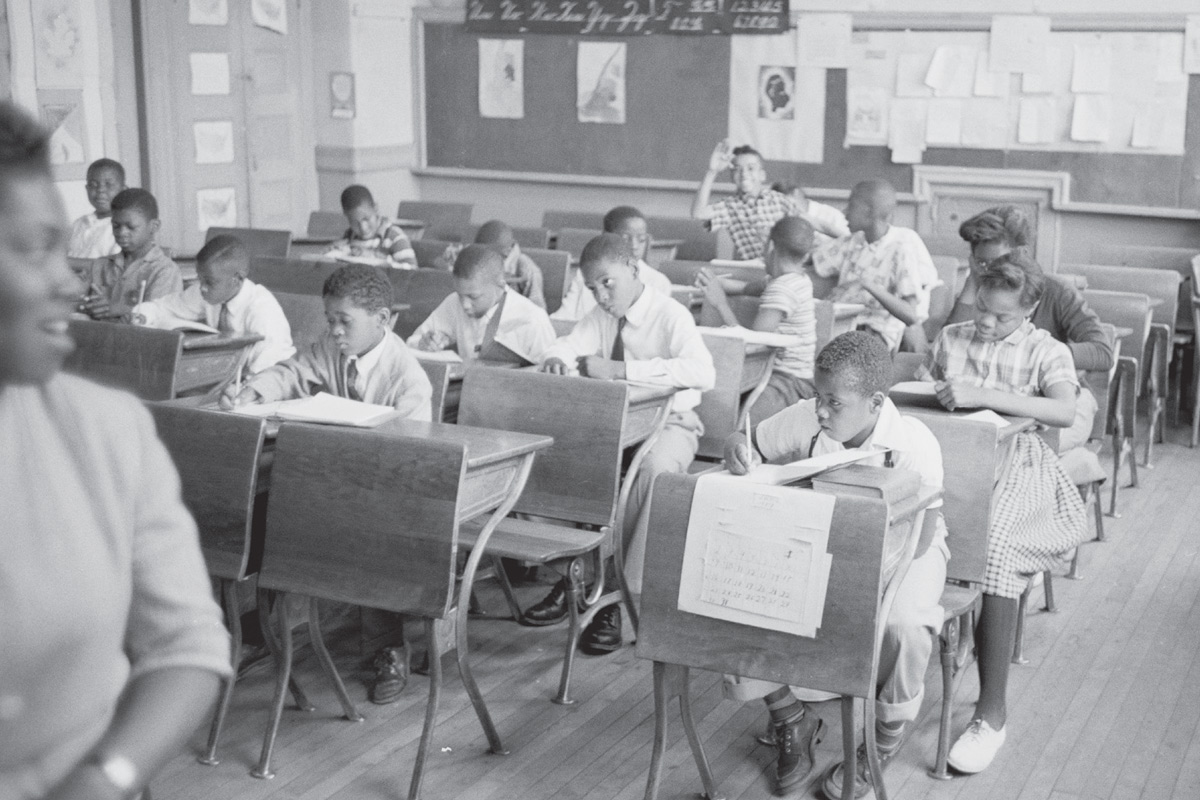

AMERICAN STORY All of the elements of the Civil Rights movement – the use of litigation to challenge inequity, the centrality of education to the struggle – are well illustrated in Harlem, Erickson argues. (Photo courtesy Ansley T. Erickson)

But where the earlier work was about the barriers created by white people, in Educating Harlem – and also in a workshop for teachers, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, that she will co-lead this summer at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture – Erickson, Morrell, and the volume’s 14 contributors present the overlooked story of how black people themselves, through the medium of education and education reform, have both navigated within and sought to erase those lines.

[Read a story and visit a website about “Harlem’s Education Movements: Changing the Civil Rights Narrative,” the workshop for teachers that Erickson and the Schomburg’s education director, Brian Jones, will co-lead this summer from July 20 through July 31. The deadline to apply for the workshop is March 1st.]

“Harlem proved key terrain in which to define what it meant to go to school as a Black person in twentieth-century urban America,” write Erickson and Morrell (a former TC faculty member who is now the Coyle Professor in Literacy Education at the University of Notre Dame). “From their arrival, residents pursued a range of innovating educational visions. To do so they worked against overcrowding and understaffing caused by systematic neglect by the city system; school resources and curricula that paid little heed to the stories and perspectives of people of African descent; policies that subtly or overtly encouraged segregation; and teaching methods that denied students’ and community members’ humanity rather than celebrating it.”

Harlem proved key terrain in which to define what it meant to go to school as a Black person in twentieth-century urban America.

—Ansley T. Erickson and Ernest Morrell

Education Harlem bills itself as the first book wholly dedicated to documenting primary and secondary education in Harlem across the 20th century. Its chapters range in focus from the Harlem Renaissance to school architecture to the post-Civil Rights era, but common themes emerge that challenge prevailing narratives about public education and black communities.

For example, the conventional view of American urban public schools is that they “rose” during the first half of the 20th century, receiving growing funding and emerging as a centralized bureaucracy with an ever-broader mission, and then declined during the latter half of the century, as industries left cities and low-income, high-need families flooded urban neighborhoods. But “black urban dwellers did not enjoy a ‘rise’ in which city schools expanded access and excelled in creating new mobility,” write Erickson and Morrell. “And although city schools, like many other aspects of urban infrastructure, faced new challenges in the post–World War II decades, their fall was never so great as to end community investment and striving via education. The variety and endurance of this struggle reveal themselves best when, as this volume does, the work of women, children and youth, and activists across a variety of ideological positions receives the historical attention it merits.”

TRAILBLAZER Gertrude Ayer, New York City's the first black, female public school principal (Photo courtesy Ansley T. Erickson)

Another, closely related theme of Educating Harlem is that while mid-century white scholars and policymakers focused on “the problem of the cities” -- an urban crisis reflecting the brutality of capitalism and what they thought was “cultural deprivation” -- the lived experience of black people themselves reflects a very different kind of story.

“The dominant discourse in the 1960s and 70s is white sociologists saying that black communities don’t care about education, and that influences policy,” Erickson said in a recent interview. “But when you see the enormous range of activism by black parents and students, you see that that narrative is a fundamental misconception. In Harlem and other cities, black parents and students are constantly working, with all the tools available to them, to make education what they want it to be.”

The dominant discourse in the 1960s and 70s is white sociologists saying that black communities don’t care about education, and that influences policy,. But when you see the enormous range of activism by black parents and students, you see that that narrative is a fundamental misconception.

—Ansley T. Erickson

Their varied approaches reinforce the assertion by Erickson and Morrell that, for all the neighborhood’s symbolism, there is no single, monolithic Harlem or Harlem education story.

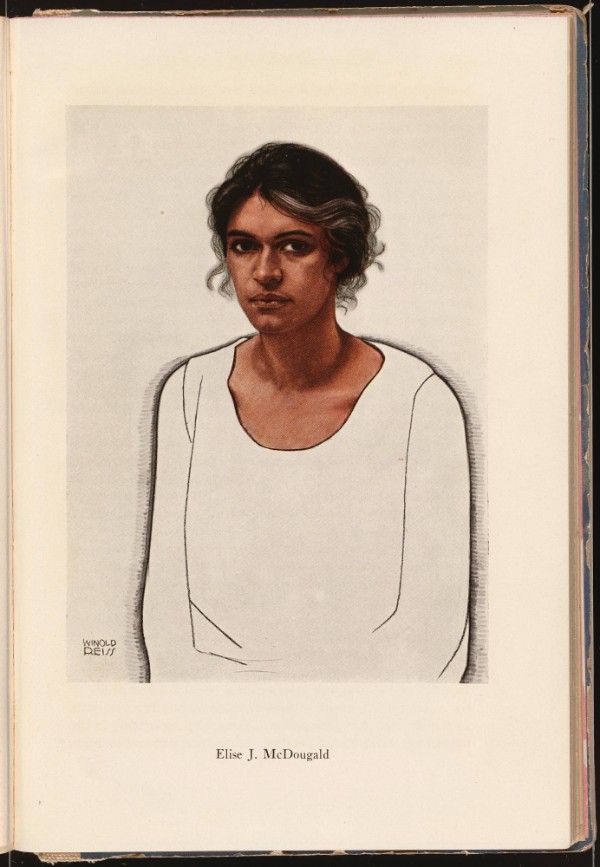

For example, in the opening chapter of Educating Harlem, “Schooling the New Negro: Progressive Education, Black Modernity, and the Long Harlem Renaissance,” Daniel Perlstein, a faculty member at the University of California at Berkeley Graduate School of Education, describes the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s as a wellspring for an “expansive vision of education for children seeking to construct a meaningful life upon what Ralph Ellison called ‘the horns of the white man’s dilemma.’” Perlstein argues that the progressive philosophies of educators such as Gertrude Ayer (the first black, female New York City public school principal) and Mildred L. Johnson Edwards, founder of Harlem’s Modern School, are rooted in “a New Negro ethos” captured in Renaissance-era novels such as Jean Toomer’s Crane and Nella Larsen’s Quicksand.

A chapter by Russell Rickford, Associate Professor of History at Cornell, titled “Black Power as Educational Renaissance: The Harlem Landscape,” considers alternative and community education efforts that arose after the 1964 Harlem street uprising triggered by the shooting of a black teenager by a white police lieutenant. The Black Power movement was “a renaissance of educational thought and practice” that included “an array of grassroots ventures [that] sought to imbue Harlem youngsters with a potent sense of racial pride and awareness,” Rickford writes.

TC History & Education doctoral candidate Esther Cyna co-authored a chapter with NYU Associate Professor of History Kim Phillips-Fein, tracing the impact of the 1975 New York City fiscal crisis on Harlem, and the protests that residents waged to protect their schools and institutions from closures and other austerity measures. Cyna also assisted Erickson and Morrell with the editing of the volume.

And in a chapter titled “Teaching Harlem: Black Teachers and the Changing Educational Landscape of Twenty-First Century Central Harlem,” TC Sociology & Education alumna Terrenda White (Ph.D. ’14) (Assistant Professor of Sociology & Education at the University of Colorado, and coauthor Bethany Rogers, Associate Professor at the College of Staten Island and CUNY Graduate Center, reflect on the “special place” that teaching has long occupied in the history of African American communities.

“The questions of who taught and who should teach animated debates over community control in the 1960s, reflected both compliance and resistance to central school district mandates in the 1980s, and took on new meaning in early twenty-first century Harlem, given an educational landscape with a large and growing number of charter schools,” write White and Rogers.

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision to strike down segregated schooling, nearly 40,000 black teachers lost their jobs nationwide, but the number of teachers of color in Harlem rose sharply from 1972 on — particularly in District 5 schools. White and Rogers attribute that increase to several factors, including the de facto segregating of black teachers to black neighborhoods, the emergence of alternate routes to teaching, the development of new models of school governance, and “curricular and pedagogical priorities tied to accountability and market-based competition charter schools.” There are positives and negatives to each of these trends, but, the authors conclude, “one outcome that has remained elusive through these years is the development of a stable, diverse, cadre of teachers who are well-prepared to teach District 5 students.”

“Ernest [Morrell] and I are grateful to everyone involved for creating such important content and making it readily available,” Erickson said. “The book was created in hopes of stimulating dialogue between past and present.” In keeping with that goal, a book launch in Milbank Chapel at TC on March 24 at 5:30 pm will bring the co-editors into conversation with teachers, educators, and other activists who will speak to how Harlem’s important history can inform education today.