It’s a recurring trend in American education: The blockbuster report that finds widespread mediocrity and failure, particularly among schools and districts that serve low-income and minority students, and sounds the alarm for badly needed reform.

Often these documents have been written by well-intentioned critics who genuinely seek education for under-served groups. But a new book edited by TC’s Mariana Souto-Manning, Professor of Early Childhood Education, makes a powerful case that the “rhetoric of educational failure” in reports such as “A Nation at Risk” and undergirding federal legislation such as No Child Left Behind has been a key means of narrowly defining literacy in ways that reinforce white privilege and disenfranchise students of color and those typically labeled English language learners.

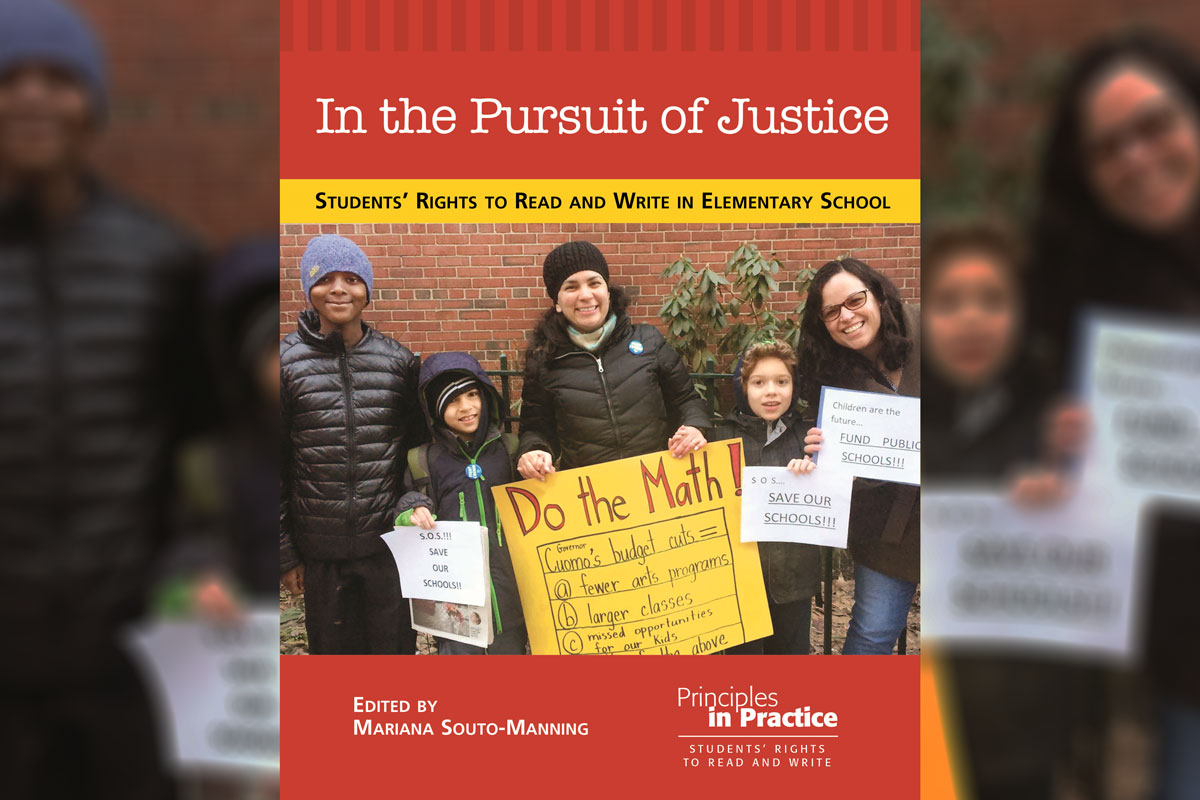

CONTEXTUALIZING LITERACY Souto-Manning calls for approaches that “honor children’s ways of knowing.” (Photo: TC Archives)

The book, In the Pursuit of Justice: Students’ Rights to Read and Write in Elementary School, is published by the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and is framed by two NCTE position statements, The Students’ Right to Read (2018) and NCTE Beliefs about the Students’ Right to Write (2014). In the Pursuit of Justice includes essays by eight New York City public school teachers — including several TC instructors and alumni who have worked closely with Souto-Manning.

The notion that calling out educational failure amounts to blaming the victim might seem counter-intuitive. But in her opening essay, Souto-Manning argues that by “narrowing what counts as literacy,” reports such as A Nation at Risk — which charges that “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war” — have “constructed children and youth of color as risks” and “sanctioned racial, cultural, and linguistic inequities as acceptable.”

Souto-Manning argues that by “narrowing what counts as literacy,” reports such as A Nation at Risk have “constructed children and youth of color as risks” and “sanctioned racial, cultural, and linguistic inequities as acceptable.”

More specifically, A Nation at Risk labeled up to 40 percent of 17-year-olds of color as “functionally illiterate” compared with 13 percent of the general population. Souto-Manning points out that “without an explanation of the structural constraints and societal inequities framing such a ‘gap,’ the report constructed youth of color as risks.” Commercial publishers responded by flooding the market with “reading and writing materials that did not reflect the backgrounds and experiences of many students” and “served to dismember literacy — pulling away parts and decontextualizing them, as is the case of many phonics programs that do not include actual books — and to disempower children’s ways of knowing.”

ON THE GROUND PERSPECTIVES Souto-Manning's book features contributions by eight New York City public school teachers, including TC alumnus Billy Fong and current doctoral students Karina Malik (center) and Jessica Martell. (Photos: TC Archives)

In their essay, “Students’ Rights to Read and Write about Homophobia and Hate Crimes,” TC doctoral student Jessica Martell and alumnus Billy Fong (M.A. ’11), fourth/fifth-grade co-teachers, discuss how they focused their class on the 2016 mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Sharing their own concerns and discomfort with the topic, they explain how they designed activities that fostered students’ reading and writing development and allowed them to explore social injustice.

And in “Students’ Right to Trauma-Informed Literacy Teaching,” first-grade teacher Karina Malik (M.A.’14 and current TC doctoral student) describes how she cultivates a supportive “trauma-informed” classroom where youngsters who have witnessed violence or are dealing with homelessness or other stresses are empowered to address those experiences, both orally and in writing.

Souto-Manning also reaffirms NCTE’s call for schools to protect children from censorship. She notes that at a public school that is home to several of the book’s contributing teachers, a visual literacy project authored by students in a kindergarten was attacked by conservative bloggers after it was critiqued by conservative commentator Sean Hannity. Charging that the school did not adequately protect students, she asserts that NCTE’s anti-censorship positions “not only seek to protect students’ rights to read and write, but also serve as much-needed reminders that these are rights, not privileges to be dispensed as rewards or in ways that foster disproportionality.”

Souto-Manning and all teacher collaborators will be facilitating a free monthlong discussion about the book and offer insights, resources, and ideas for teaching in the pursuit of justice. This is part of NCTE Reads, sponsored by the National Council of Teachers of English. Anyone interested can register here.

— Joe Levine