“The idea of emptying your mind is an illusion — it won’t work, and it’s not our goal. Just focus on your breathing and observe your thoughts. The key is not to attach to them, because that’s when we ruminate and suffer.”

The scene was a Teachers College classroom this past January, where Angel Acosta was leading New York City educators in a meditation exercise as part of a workshop he was conducting for the Kellogg Foundation’s National Racial Healing Day. Soon the group would view a 400-year timeline of major injustices against people of color, Native Americans, women, low-income white laborers and other marginalized groups in American society.

“We use meditation and mindfulness to achieve greater wellbeing,” Acosta said softly, as people sat with eyes closed. “But how can we also meld being self-aware with a situation of the most gross inequality? How can we combine the benefits of mindfulness to respond to the raw realities of our society?”

Angel Acosta: Ed.D., Curriculum & Teaching

Acosta projects kindness, calm, optimism and quiet strength. But with people of color dying from COVID at significantly higher rates than whites, and with the recent police killings of George Floyd and other unarmed black people, Acosta, who is both black and Dominican, acknowledges that he has found those realities especially raw.

I feel incredible levels of anger. Having to negotiate whether to go protest or avoid COVID infection — is this really where we are? But my work allows me to channel my anger. I know how to move it through my body.

— Angel Acosta

“I feel incredible levels of anger,” he said in June, soon after receiving his TC doctorate in Curriculum & Teaching. “The heat from it is like magma, and it’s compounded by deep frustration. Having to negotiate whether to go protest or avoid COVID infection — is this really where we are? But my work allows me to channel my anger. I know how to move it through my body.”

Acosta’s work (he consults for organizations that have included UNICEF, the New York City Department of Education and Columbia University), and the focus of his Teachers College dissertation, is “healing-centered education,” a term that integrates approaches such as social and emotional learning, restorative justice, racial literacy and trauma-informed teaching.

Graduates Gallery 2020

Meet some more of the amazing students who earned degrees from Teachers College this year.

“It’s crucial for educators to structure opportunities for students to practice critical thinking about systems that perpetuate harm — for example around racism,” he says. “But what does it mean to think constantly about racial disparity? Teachers are experiencing burnout and overwhelm, often because of the trauma that students are bringing to class, or the traumas that they themselves experience because of their racialized identities. So it’s equally important to practice and teach self-care.”

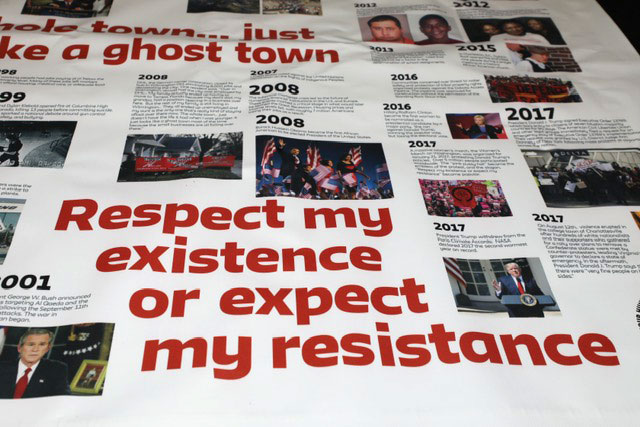

TRAIL OF TEARS The 400 Years of Inequality timeline details major injustices against people of color, Native Americans, women, low-income white laborers and other marginalized groups in American society. (Photo: Maria Vullo)

Acosta’s contemplative timeline experience — in his words, “a contemplative and mindfulness-based learning experience” he created that is also part of a larger initiative called 400 Years of Inequality (co-chaired by TC adjunct professor Robert Fullilove, who is Associate Dean for Community & Minority Affairs and Professor of Clinical Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health) — attempts to reconcile those seemingly disparate goals at a level that is at both immediate and profoundly historical.

“The impact of trauma on the brain is real,” he says. “This, and the fact that we struggle to process difficult historical material like the past 400 years of inequality results in an inability to honestly confront our past.”

Acosta’s approach bears some resemblance to a technique called flooding, in which, under controlled circumstances, patients sit with the feelings caused by past traumatic events. At the workshop in January (and in subsequent virtual iterations), participants spend half an hour silently viewing a vast poster consisting of key dates in American history, with explanatory blurbs. [Click here to sign up for virtual experiences Acosta will host this summer.]

The entries include:

1636: Massachusetts builds America’s first slave carrier, launching the slave trade.

1674: New York determines that blacks who converted to Christianity after their enslavement would not be freed.

1855: Enslaved black women are legally denied rights to self-defense in rape or sexual assaults.

There’s also reference to the Trail of Tears (the forced relocation of approximately 60,000 Native Americans from their ancestral homelands); the final Seminole War, after which fewer than 200 members of the Seminole tribe remained in Florida; and the 1910 decision by the American Federation of Labor to continue excluding female and black workers from its membership.

Afterwards, the workshop participants write journal entries and speak in pairs and then as a group about the feelings they experienced in viewing the timeline.

HEALING AND STRUCTURAL CHANGE Participants in the Contemplating 400 Years of Inequality experience talk about their feelings, but also about strategies for reform. (Photo: Maria Vullo)

“There’s been a great failure in our country to process or metabolize that history,” Acosta says. “As the Reverend William Barber III has asked, what does it mean to be part of a country with such a contradictory legacy? That built its entire empire on free labor? We haven’t really come to terms with that.”

Acosta’s own history prepared him, on many levels, for his current work.

He grew up on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. His parents, who were born in the Dominican Republic, struggled financially. By his own admission, he was “an average student” who might easily have taken the “wrong path in life” but for sports and an organization called College for Every Student (CFES Brilliant Pathways), which helps middle school and high school students from low-income families prepare for college.

Helped by teachers in high school and at CFES to study and hone his leadership skills, Acosta attended the State University of New York at Plattsburgh, becoming the first member of his family to go to college. After earning a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology and a master’s in Leadership Studies, he worked for nine years as a program director for CFES, helping to mentor hundreds of students in the United States and addressing many more in countries around the world. He became increasingly interested in the relationship between mindfulness and social justice education, participating in leadership programs at the Mind & Life Institute. Later, he joined the board of the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society.

There’s been a great failure in our country to process or metabolize that history. As the Reverend William Barber III has asked, what does it mean to be part of a country with such a contradictory legacy? That built its entire empire on free labor? We haven’t really come to terms with that.

— Angel Acosta

At Teachers College, where he was unanimously chosen as the inaugural Anne R. Gayles Felton Endowed Scholar, Acosta decided to dedicate his life to “incorporating healing-centered pedagogies and mindfulness into tough conversations around structural inequality.” Working closely with his advisor, Professor of Education Celia Oyler, and with Associate Professor of English Education Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, he honed what he calls a “transformative activist stance” toward research — an approach to research based upon the work of Anna Stetsenko, of the CUNY Graduate Center, in which “the world isn’t static and the researcher isn’t purely objective.” At the heart of that outlook, he says, is the importance of the researcher’s relationships with those who participate in the research.

“You are a web of relationships that connect to the research site and the participant.” he says. “You need to tend to the integrity of that relationship the ethical implications of your work, both to preserve harmony and to not cause harm. Especially when you are looking at marginalized populations, which have historically borne the brunt of harm caused by qualitative and quantitative research.”

My relationship to hope is hope as practice -- not a false sense of idealism. It needs to be enacted daily. If not, you can lose your mind in a society experiencing this kind of turmoil and crisis.

— Angel Acosta

For his dissertation, Acosta spent six months observing a group of New York City public school teachers, most of whom were of color, who, as part of a professional development experience sponsored by the New York City Department of Education, were meeting regularly at TC to explore racial literacy and healing. His study, for which he uses the anthropological term “thick description,” looks at conditions needed to create a learning community that thrives on that interconnectedness.

“It’s too small a study for me to make any generalization that applies to the broader population, but what I saw is that creating a restorative or healing space to explore racialized stress creates feelings of belonging and gratitude, and an enhanced sense of empathy toward others and oneself. It also creates the kind of community that we so badly need in our society, especially in this pandemic, which has revealed both how fragile we are as a civilization and the primacy of our inter-connectedness.”

Acosta has been buoyed by the recent global protests calling for racial justice, which he compares to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, but he calls himself a realist.

“It’s going to be a cycle of tragedies and responses until we get things right and make structural change,” he says. “Some people will come home from the protests and they’ll forget. But I’m part of the communities that will never forget, and I say that COVID-19 and this most recent wave of structural violence by way of police brutality is forcing everyone to become more informed about how trauma impacts the body, the mind and the community. And that gets to healing centered education. It’s going to push scholars to focus on collective trauma and healing and how curricula can integrate ways for students, teachers and professors to process trauma and foster healing, which includes grief and resentment and the messiness of what comes up.”

Ultimately, he says, the country needs to establish truth and reconciliation committees like those created by Canada to document injustices against its indigenous First Nations peoples; by South Africa in the wake of apartheid, and by Rwanda following the genocide there.

“There’s never been a federal push, but different efforts such as those by Bryan Stevenson [founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, which fights unfair prison sentencing], the lynching museum [The Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama] and the National Museum of African American History and Culture all attest to the need for that conversation. That’s what this moment is bringing us to.”

Getting there will be neither simple nor quick, “but my relationship to hope is hope as practice — not a false sense of idealism. It needs to be enacted daily. If not, you can lose your mind in a society experiencing this kind of turmoil and crisis.”

— Joe Levine