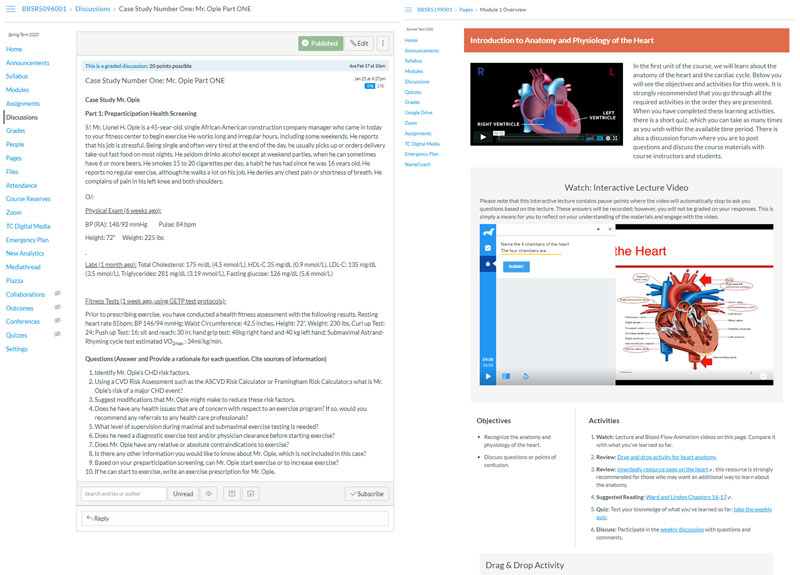

Carol Ewing Garber likes to use a problem-based case-study model in her teaching. Consider this semester’s course, “Advanced Exercise Prescription.” Each week, Garber — Professor of Movement Sciences — asks her students to consider a fictitious patient who would like to begin an exercise regimen but has various health constraints. The students get information on why the person wants to exercise and what his or her health issues are, along with information about those conditions. Then they decide: Is it safe for this person to exercise? Should any precautions be taken? What symptoms should be watched for? What are the risks and benefits of exercise? And then they make an exercise prescription.

“There’s no single right answer to these cases,” Garber says. “The students need to do the readings, look for additional information, post responses to the questions, and interact with each other about what they’ve posted.”

It’s a great format for the current crisis, especially since many of Garber’s students have returned home to other time zones. But Garber has actually been teaching the course — and several others – online or in mixed format for several years now.

“I find that group work goes especially well when I teach asynchronously,” she says. “The students work together in pods privately, instead of in a crowded room where each pod is overhearing all the others. This format also allows each student’s voice to be heard and is often more comfortable for shy students. It’s really enhanced the ideas they come up with.”

Distance, it seems, can also make for greater engagement. That’s true visually in classes where she teaches about research, Garber says. “Some people like it better on screen. It’s like the opera — you can hear better, and you get an unobstructed view, with the camera zeroing right in on the performers.”

HEART TO HEART Carol Ewing Garber's anatomy classes are asynchronous, but she finds ways to connect with students personally. (Photo: TC Archives)

But intellectual objectivity may be even more important.

“We always study ethical issues in my seminar,” Garber says. “Groups get assigned hypothetical cases such as in which a person might be old or obese, or conversely, young or fit. They have to respond to questions about how they’d interact with that person in a research or clinical setting, not realizing that the pictures they’re seeing may be different than those the other groups see. We also do exercises around gender biases and around gender roles. Recently, we asked about different tasks or work people might do — is that associated with a man or a woman? We do this because we do very applied human research. So, it’s helpful to see that, oh, I might have this bias, which can actually impact my data and how I treat my research participants.”

The lesson of COVID is how not to lose that personal connection. Send out notes, messages, emails, texts, and short personal videos. The big takeaway is that we don’t have to think in terms of online versus offline. We can merge the best of both.

— Carol Ewing Garber

Garber says she’s mindful of the need to maintain a personal link to students.

“The lesson of COVID is how not to lose that personal connection,” she says. “Send out notes, messages, emails, texts, and short personal videos. Make sure students know they can reach out to you with emails or video clips, or live. It may take a little more time out of your schedule, because even when we’re physically at TC, office hours often don’t work. What’s convenient for the professor may not work for the students. So virtual office hours are great, if you can be flexible.”

“The big takeaway is that we don’t have to think in terms of online versus offline,” she says. “We can merge the best of both.”