Nobody could have fully predicted the COVID-19 crisis and how it would change education. But as a new generation of digital learning tools has emerged in recent years, a growing cross-section of faculty members at Teachers College have discovered that online instruction can sometimes be as effective and rewarding — and maybe even more so — than teaching in a physical classroom.

Here are the stories of five TC professors and how they have adapted to virtual teaching.

Practicing the Inclusion She Preaches: Angel Wang

Angel (Ye) Wang, Professor of Deaf & Hard of Hearing and Co-Director of TC's Institute for Psychological Science and Practice (Photo: TC Archives)

As Professor of Deaf & Hard Hearing, Angel (Ye) Wang, puts a premium on interaction in her courses. Her seminar for doctoral students, which deals with all areas of disability, includes a weekly “book club,” with students taking turns leading the class.

“I want my students to broaden their horizons and be good teachers and good human beings, so we read books about education, psychology and health,” Wang says. This semester’s list includes Mind in Motion, by TC psychologist Barbara Tversky; Gender and Our Brains, by Gina Rippon, a cognitive neuroimaging scientist at the Aston Brain Centre in the United Kingdom; How the Other Half Learns: Equality, Excellence, and the Battle Over School Choice, by Robert Pondiscio of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute; The Disordered Mind, by Columbia University Nobel laureate Eric Kandel; Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity, by Steve Silberman of Wired magazine; and (one of Wang’s personal favorites) Accidental Brothers: The Story of Twins Exchanged at Birth and the Power of Nature and Nurture, by Nancy Segal, an evolutionary psychologist at California State University at Fullerton, and Yesika S. Montoya, Associate Director of Advising and an adjunct faculty member at the Columbia University School of Social Work.

“It’s really discussion-based,” she says.

Not surprisingly, then, Wang initially had doubts about conducting class on Zoom. But she credits Minh Le, ODL’s Educational Media Developer, with helping her to see the medium’s potential.

In the past she has always made accommodations for deaf or hard-of-hearing students in the class, providing those students with both live captioning and two sign-language interpreters. But now, using Zoom for the first time in her career, Wang is able to provide captioning for all students in the class.

It turns out that the captioning is also very helpful for our other students, both in following what is going on in class and in thinking about it afterward, because I also send everyone the transcript when requested. Students who were previously very quiet — particularly international students, who often were struggling to keep up in what may be their second or third language — are now much more involved.

— Angel (Ye) Wang

“It turns out that the captioning is also very helpful for our other students, both in following what is going on in class and in thinking about it afterward, because I also send everyone the transcript when requested,” she says. “Students who were previously very quiet — particularly international students, who often were struggling to keep up in what may be their second or third language — are now much more involved. Partly it’s the captioning, but Zoom also has a raise-your-hand feature, and in my class now, there’s always a queue. It’s very orderly but it makes things more interactive — maybe because people have more time to think.”

Wang says she plans to continue using captioning for the entire class even when TC returns to holding classes on campus. But beyond making for a livelier class, she adds that Zoom is also serving as an object lesson for the students — most of whom are K-12 teachers struggling to figure out how to best serve their own students right now.

“It’s like the principles of universal design in architecture, which I often talk about — the way that wheelchair ramps benefit people with strollers, too,” Wang says. “The people in my class are using what they learn, often the very next day, and some are teaching online to preschoolers — imagine that! And if you ask them what they find most different about teaching online, they’ll tell you it’s the involvement with parents. A lot of them are doing individual sessions with parents and kids.”

If Wang had any lingering reservations about Zoom, they were dispelled recently when five graduating doctoral students in the program — including one who is deaf — conducted a webinar on frontiers in deaf ed. The event, held in the evening, drew some 100 people on Zoom, including many alumni and viewers from outside TC.

The bottom line for Wang: “I find that all these online features that people thought were problematic can be beneficial for everyone.”

An Exercise in Eliminating Bias: Carol Ewing Garber

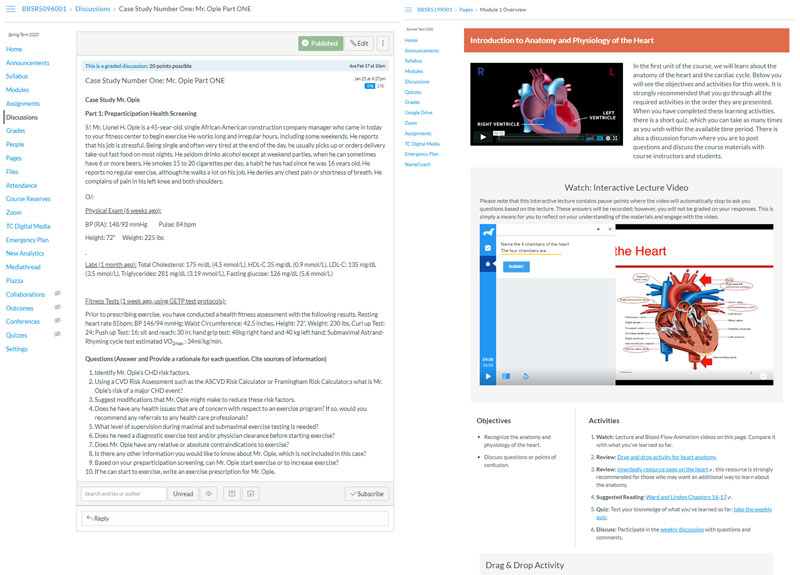

Carol Ewing Garber likes to use a problem-based case-study model in her teaching. Consider this semester’s course, “Advanced Exercise Prescription.” Each week, Garber — Professor of Movement Sciences — asks her students to consider a fictitious patient who would like to begin an exercise regimen but has various health constraints. The students get information on why the person wants to exercise and what his or her health issues are, along with information about those conditions. Then they decide: Is it safe for this person to exercise? Should any precautions be taken? What symptoms should be watched for? What are the risks and benefits of exercise? And then they make an exercise prescription.

“There’s no single right answer to these cases,” Garber says. “The students need to do the readings, look for additional information, post responses to the questions, and interact with each other about what they’ve posted.”

It’s a great format for the current crisis, especially since many of Garber’s students have returned home to other time zones. But Garber has actually been teaching the course — and several others – online or in mixed format for several years now.

HEART TO HEART Carol Ewing Garber's anatomy classes are asynchronous, but she finds ways to connect with students personally. (Photo: TC Archives)

“I find that group work goes especially well when I teach asynchronously,” she says. “The students work together in pods privately, instead of in a crowded room where each pod is overhearing all the others. This format also allows each student’s voice to be heard and is often more comfortable for shy students. It’s really enhanced the ideas they come up with.”

Distance, it seems, can also make for greater engagement. That’s true visually in classes where she teaches about research, Garber says. “Some people like it better on screen. It’s like the opera — you can hear better, and you get an unobstructed view, with the camera zeroing right in on the performers.”

But intellectual objectivity may be even more important.

“We always study ethical issues in my seminar,” Garber says. “Groups get assigned hypothetical cases such as in which a person might be old or obese, or conversely, young or fit. They have to respond to questions about how they’d interact with that person in a research or clinical setting, not realizing that the pictures they’re seeing may be different than those the other groups see. We also do exercises around gender biases and around gender roles. Recently, we asked about different tasks or work people might do — is that associated with a man or a woman? We do this because we do very applied human research. So, it’s helpful to see that, oh, I might have this bias, which can actually impact my data and how I treat my research participants.”

The lesson of COVID is how not to lose that personal connection. Send out notes, messages, emails, texts, and short personal videos. The big takeaway is that we don’t have to think in terms of online versus offline. We can merge the best of both.

— Carol Ewing Garber

Garber says she’s mindful of the need to maintain a personal link to students.

“The lesson of COVID is how not to lose that personal connection,” she says. “Send out notes, messages, emails, texts, and short personal videos. Make sure students know they can reach out to you with emails or video clips, or live. It may take a little more time out of your schedule, because even when we’re physically at TC, office hours often don’t work. What’s convenient for the professor may not work for the students. So virtual office hours are great, if you can be flexible.”

“The big takeaway is that we don’t have to think in terms of online versus offline,” she says. “We can merge the best of both.”

Statues with Limitations: Detra Price-Dennis

Detra Price-Dennis won’t pretend otherwise: She and her TC students were devastated when the COVID pandemic forced them to work remotely.

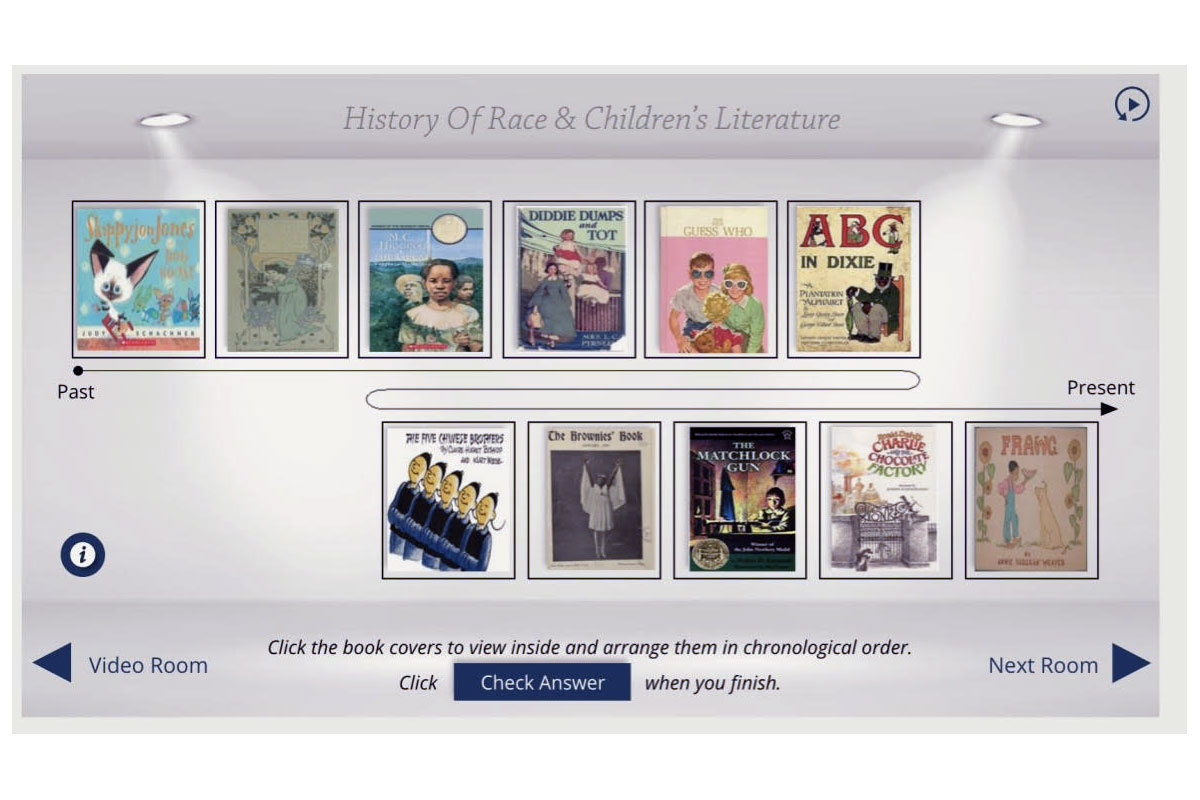

That’s out of character for someone who — literally — has been an avatar of online education. A few years ago, for TC’s annual Reimagining Education Summer Institute, Price-Dennis, Associate Professor of Education, created a virtual museum, complete with a gift shop and a maker space, in which, docent-like, she leads “visitors” on a narrated tour.

“I wanted to try something different — an immersive virtual experience for my modules,” she says. She laughs. “I went to Minh Le in the Office of Digital Learning, thinking he’d throw me out, but he said “yes” before I even said what it was.”

But some things really can’t be done virtually.

That, sadly, is the case with a year-long project that Price-Dennis and her TC students were conducting with a teacher, Noelle Mapes (M.A. ’15), and her second graders at P.S. 142 on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. In the fall, the youngsters looked at local city monuments, learning about the people whom they honor and why.

BOOKS, WINDOWS AND MIRRORS Price-Dennis's online modules for teachers have often focused on the importance of using literature that mirrors student diversity. (Photos: TC Archives)

A consistent finding was that most of the statues look nothing like the people in the neighborhood. So, during fall and spring semesters, the second graders researched monuments, interviewed community members they admired, and worked with TC students to design and construct prototypes of new monuments to honor them using 3D printers and other tools in TC’s Transformative Learning Technologies Laboratory. During spring semester, they had just started working on a podcast when schools were abruptly closed due to COVID-19.

At first, after school buildings were closed, everyone wanted to somehow continue — “but it was too hard to do breakouts online with second graders in their homes in New York City and many of my own students in China and California,” Price-Dennis says.

I didn’t anticipate the emotions coming through in [students’] animations. They expressed a need for community, and a need for ways to talk to material and make sense of it.

— Detra Price-Dennis

The TC students have since created their own animations to express their reactions to articles they’ve read about engaging youth in research, and how young children are experiencing online learning during the COVID crisis. They shared their creations with family members and one another via a tool called Padlet, and more recently have collaborated on a policy statement about online learning.

“I didn’t anticipate the emotions coming through in their animations,” Price-Dennis says. “They expressed a need for community, and a need for ways to talk to material and make sense of it.”

It’s all good work, Price-Dennis says, “but Noelle and I want to continue our project in the fall. We want to ask the kids, What is this new world? Can you create an alternate reality experience? They all have iPads. TC students would support them. But it depends on whether or not we go back on campus. With eight-year-olds, you need high touches. You can’t do this type of work very well virtually.”

Using Technology to Bridge Disciplines: Laudan Jahromi

When Laudan Jahromi decided to create a fully online master’s degree program in Developmental Disabilities, her logic was simple: The field already had a foot in other disciplines, so why not make its content fully accessible to psychologists, health practitioners, lawyers, policymakers and others working fulltime jobs — including those in other countries?

In her own online courses, Jahromi, Professor of Psychology & Education, did worry about her ability to check in on students’ levels of reflection and understanding about a field that has evolved so rapidly.

For example, in Jahromi’s course Working with Families of Children with Disabilities, students reflect on the changing role of parents in this field. “The experiences of families of children with disabilities have changed dramatically in the United States over the past several decades,” she says. “It wasn’t that long ago that parents played a secondary role. Practitioners would say, ‘Put your kid in an institution — that’s the best option.’ Today, parents drive the decisions for their children in special education. Schools need their participation to ensure positive outcomes.”

When I teach on campus, I meet with my class for an hour and 40 minutes, and then I hold office hours at set times. But when I teach online, asynchronously, students respond to course materials on their own time. The discussion goes on all week, and if I want to be part of it and help keep it going, I have to chime in.

— Laudan Jahromi

Jahromi worries that many of her students “come from the current mindset and take it for granted.” Only by appreciating the importance of how far we have come, she says, can students understand the need to be fierce advocates for those parents whose voices are still not heard.

“We’re not done yet ensuring that parents in this country have agency,” she says. “Many still face poverty and ethnic discrimination on top of their child’s diagnosis, and as a result they may have less access to services.

“When I teach in person, I often realize, ‘Hmm, they may not have thought about it this way,’” she says. “I’ll stop and ask, ‘How do you think about parents’ experience of disability historically in the U.S.?’ That way, I know whether I need to place greater emphasis on how much has changed. And then at the end of class I might ask, ‘So where are you now with your thinking, relative to where you were earlier?’”

Thanks to a tool called PlayPosit, recommended by ODL, Jahromi can still achieve the same dynamic process of teaching in her asynchronous course.

“I’ll pre-record my lecture, but at different points I’ll still say, ‘Think about what this concept means to you right now.’ And through PlayPosit, a window pops up for the students asking: ‘What do you think about that topic?’ They type in their answers, and later I see their responses. So, they’re engaging with me even though I’m not there. I can measure changes in their thinking and I can give them feedback.”

In fact, like Angel Wang, Jahromi believes that discussions in her class have, if anything, become richer and more rigorous.

“Online, the students who don’t usually speak up in class tend to come out of their shells,” she says. “They can go in-depth, and I know them more intimately.”

The only caveat: To get that kind of interaction, the instructor may have to be willing to put in more time.

“When I teach on campus, I meet with my class for an hour and 40 minutes, and then I hold office hours at set times. But when I teach online, asynchronously, students respond to course materials on their own time. The discussion goes on all week, and if I want to be part of it and help keep it going, I have to chime in. ODL really helped me to adapt to this structure.”

The Art of Scaling Up: Richard Jochum

Richard Jochum, Associate Professor of Art & Education (Photo: TC Archives)

Not long after TC moved to remote teaching in March, Richard Jochum tried to start class on Zoom one evening by doing an emotional check-in with his students.

“I said, ‘How are you, how do you all feel?’ And a student burst out: ‘What are we doing here!’ I was surprised because he’d written to me earlier that he was fine. When I spoke with him about later, I said, ‘You’re frustrated,’ and he said —‘Yeah, I don’t know if I’ll be alive in two weeks.’”

For Jochum, Associate Professor of Art & Art Education, the moment was a cautionary tale on several levels.

Ultimately, I believe we’ll look back on this time and think: We became better teachers, too.

— Richard Jochum

“I realized, ‘One needs to cautiously balance these types of explorations in class,’” he says. “But also, in general, ‘Don’t try to everything right now. Be generous to yourself and your students, because we’re still in an emergency mode here. It’s important to scale up slowly.’”

Jochum and other instructors in his program have literally taken that approach when it comes to teaching the College’s studio classes in painting and sculpture. Holding these classes online would be challenging under the best of circumstances — but it’s even tougher when no one, including the instructor, has access to essential materials and tools.

Still, Jochum says, “even in sculpture, we’re doing great stuff. We can’t do welding or use our workshop, but we can still give assignments that require students to apply and refine core principles — for example, by using a cardboard box to create an installation, uploading a photo of it, and then playing with the proportions.”

Students are often more at home in the digital medium than instructors, but for Jochum, there are two essentials task in teaching — regardless of the medium and its constraints: to “create a story line from the get-go” and to provide students with a sense of community.

In his seminar this semester on Creative Technologies, he initially sought to do both by tasking his students with planning a symposium on interconnectivity in the arts. With artists everywhere now self-isolating, the topic has become even more timely, but of course, the staging an actual event isn’t possible. Nevertheless, working with Flipgrid, the class has gone ahead with creating posters for the symposium with fleshed out topics and potential speakers.

“I’ve organized one or two symposia per year since I came to TC, and I think it’s a very valuable experience for students to learn to do it,” Jochum says. “You need a strong brief and a strong call that attracts people, and when you’ve got that the rest happens on its own. So again, storyboarding is key.”

More recently, Jochum gave himself an intriguing assignment. At the suggestion of a colleague, and working with technology provided by ODL, he’s recreated TC’s Macy Gallery as a three-dimensional online space. (Click here to visit Jochum’s online 3D Macy Gallery.) Instructors can use it to post student projects and deliver end-of-semester critiques — but it can also be used for a full-on exhibition, and in July, the Art & Art Education program will do just that, with a show devoted to student work.

“I think the trick with technology is to leverage what you know, proceed slowly, and continually stretch yourself just a little bit beyond your comfort zone,” Jochum says. “Teaching online gives us a new lens for thinking about our teaching in the classroom. Ultimately, I believe we’ll look back on this time and think: We became better teachers, too.”

— Joe Levine