TC’s Office of Digital Learning (ODL) has been winning plaudits for helping the College improve its online teaching during the COVID crisis.

Now it can claim credit for facilitating humanitarian missions, too.

That, in essence, is the service that ODL recently rendered to Catherine Crowley and her students in TC’s Communications Science & Disorders Program (CSD). For the past eight years, Crowley, Professor of Practice, has been bringing students to the Colombian city of Neiva to work with children rehabilitating from cleft palate surgery. Officials in the city, which is the capital of the country’s mountainous Huilo region, have come to rely on the visits, which have helped seed the growth of cleft palate speech therapy expertise there. Crowley’s students view the trip as a major highlight, as well.

HUMANITARIAN FOCUS Crowley has been honored for her work in Colombia, Ghana and other nations where she has helped seed the field of speech pathology. (Photo: TC Archives)

“For many of us, especially those who are Spanish speakers, this is an opportunity to interact with patients and immerse ourselves linguistically in a clinical environment,” says second-year student Sayume Romero. “It was a huge reason why I chose TC. A lot of speech pathology programs are not as multiculturally focused, but it is well known that TC is the place to go if you want to study multilingual and multicultural speech pathology.”

“I’m half Colombian so I was so excited about making the trip,” says second-year student Tiffany Neira.

Everyone was deeply disappointed, then, when the COVID pandemic forced Crowley to move her cleft palate course online and scrap this year’s visit — until Crowley approached Educational Specialist Nafiza Akter in the Office of Digital Learning.

“I came in with a problem, and Nafiza had the solutions,” Crowley says.

A key part of the curriculum in Crowley’s course is skill-building. Her students learn how to produce, with their own voices, the errors that youngsters born with cleft palate commonly make to compensate for their condition. They acquire the particular therapy strategies employed by cleft palate speech experts. And they also must log lots of experience hearing cleft palate speech because the ability to perceive these sounds is the most important tool for speech assessment and treatment.

Together Crowley and Akter developed strategies for students to acquire all of these skills through an online course.

Thanks to Nafiza and ODL, students developed the same level of cleft palate therapy skills they would have developed if they had gone to Neiva, and they also developed skills in how to do quality teletherapy.

—Cate Crowley

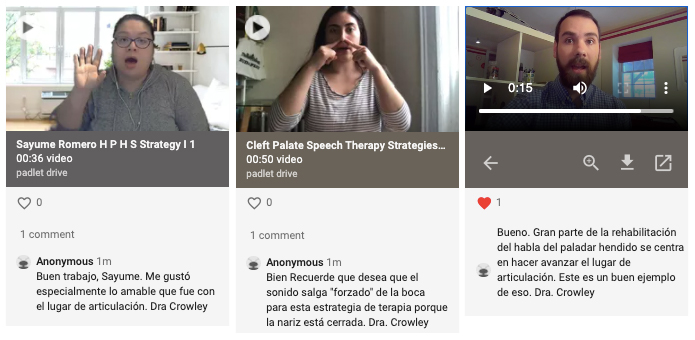

First, Crowley created videos on how to create the compensatory errors, and students had to upload short videos of themselves creating those sounds. Then she made a video showing the hierarchy of speech therapy for cleft palate and demonstrating specific therapy strategies. Students then uploaded additional videos, and Crowley gave them feedback on whether they had attained the particular parameters of each strategy.

“I wanted to be sure that students would have experiences similar to the ones they have in Neiva, where patients come in and are evaluated, and we decide on the appropriate treatment approach,” Crowley says. “I had many videos of cleft palate evaluations of real patients being conducted in Spanish, but I didn’t know how to individualize them so our students could listen, make judgments and determine the best course of therapy.”

Akter recommended PlayPosit, a software that pauses the evaluation video and poses multiple choice questions through which students demonstrate that they can perceive the sounds that patients make and then create a final summary of what they hear and decide on appropriate therapy strategies.

Some of the evaluations were required for the course, while others were available for students wanting to enhance their cleft palate therapy skills.

RAISING THEIR GAME Crowley's students (from left) Sayume Romero, Tiffany Neira and John Munday feel they improved their skills working online. They also presented with Crowley to a consortium of international experts. (Photos courtesy of Cate Crowley)

“Speech pathology is dependent on the ability of a pathologist to observe visual cues such as breathing patterns, nasal emissions and articulation of the mouth, tongue and jaw,” Crowley says. “It’s about perceiving sounds and knowing what to listen for to develop a second set of therapy strategies to move speech placement.”

“A patient with an atypical oral structure will still have errors in their speech following cleft palate surgery,” adds second-year CSD student John Munday. “We show them how to change the place of articulation to eliminate the errors. It’s almost like learning a new language, because they are not only creating sounds they’ve never made before, but also implementing those sounds into speech.”

In advance of past visits, TC students have spent long hours preparing to take what they have learned in their courses and suddenly apply them in an intensive clinical environment. Crowley knew that working clinically online would require equal, if not greater, preparation — and fortunately, she had the resources to help them do just that.

“Dr. Crowley has a vast amount of video footage, and that gave us a virtual walk-through of all kinds of multiple cleft palate cases,” says Romero. “Throughout the course I saw my own cleft palate skills develop and could see that happening with my peers.”

In mid-July, the students were ready to see patients in Colombia — via Zoom. Crowley, with her colleague, Diana Acevedo, a cleft palate expert and frequent supervisor on the trips to Neiva, and Akter, developed ways for conducting live online face-to-face cleft palate speech therapy in real time — a challenge that involves a great deal more than simply looking at a patient onscreen.

I think working through Zoom has given me and my classmates a unique set of skills.

—Tiffany Neira

“When you’re working with someone over Zoom the audio quality isn’t good as it would be in person,” says Munday. “It was sometimes difficult to tell if resonant speaking needed to be addressed with therapy or if it was digital resonance. And a lot of times, we needed a parent or a guardian to shine a light in the mouths of young children to see what structures were intact and develop a hypothesis about what we were hearing and what was going on. It definitely added an extra hurdle. But if we’d gone in person, we wouldn’t have been able to connect with as many people because of safety concerns.”

Neira sees an additional upside: “I think working through Zoom has given me and my classmates a unique set of skills.”

Zoom’s reach also has made it possible for Neira and her classmates to work remotely with patients in the United States, Spain and Ecuador. And Crowley and five of her students, including Monday, Romero, and Neira, recently did a Zoom presentation in Spanish for a consortium of 115 Colombian surgeons, orthodontists and speech pathologists on the role of the speech/language pathologist on cleft palate teams.

For Crowley, the ultimate priority is “having the skills to help a kid who at one time couldn’t be understood become a child who speaks as well as anyone born without a cleft palate.

“Thanks to Nafiza and ODL, students developed the same level of cleft palate therapy skills they would have developed if they had gone to Neiva, and they also developed skills in how to do quality teletherapy. And I know that they can bring them to patients with cleft palates that they encounter in their professional lives.”