“Neutrality” is a watchword long associated with science and its emphasis on empirical evidence. In psychology, “neutrality” conjures images of therapists in muted offices, listening without interruption

But those excluded from power in society have increasingly argued that science, and perhaps psychology in particular, reflect and reinforce the values and beliefs of dominant groups and perpetuate inequity and bias as powerfully as any other area of endeavor.

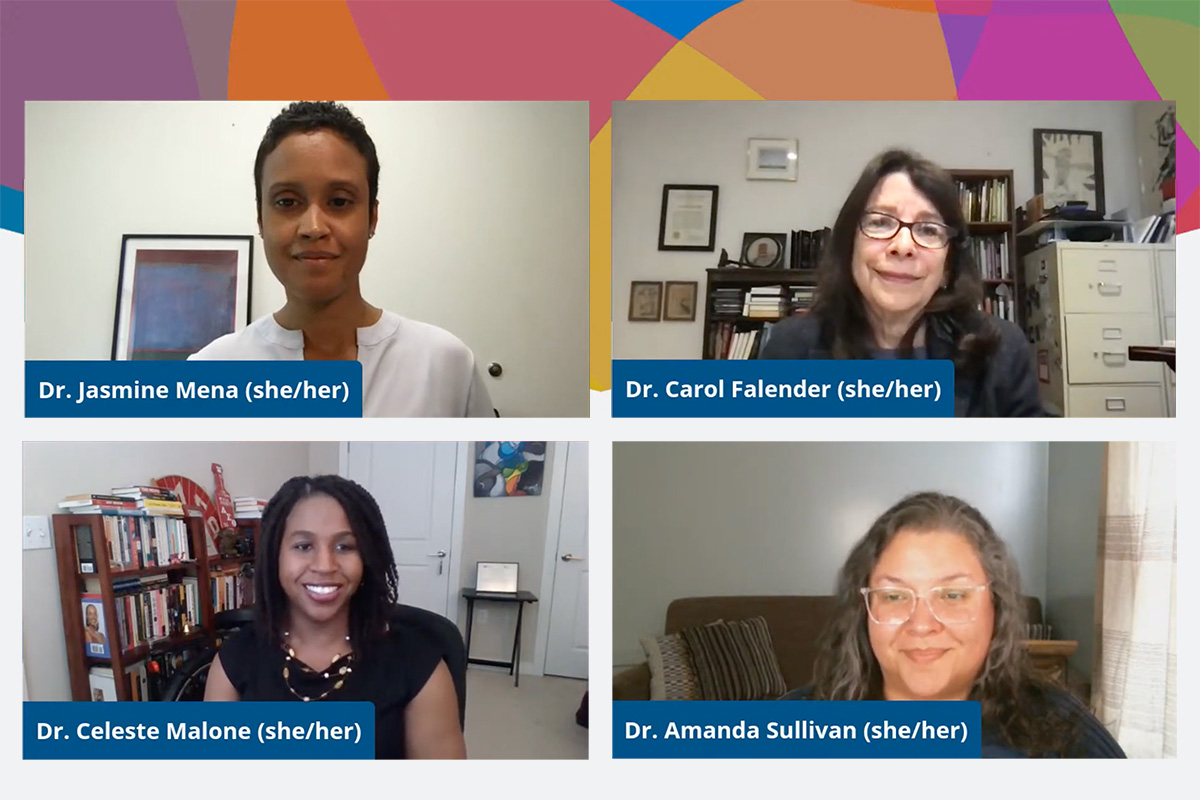

Last week’s Teachers College conference, “Decolonizing Psychology Training: Strategies for Addressing Curriculum, Research Practices, Clinical Supervision, and Mentorship,” was a remarkable show of strength for those sounding that alarm in the field of psychology.

“Psychology is a colonizer — the discipline that educates its constituents about what beliefs are acceptable and what beliefs are not,” said speaker Jasmine Mena, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Bucknell University. “And psychology is how I became ‘civilized.’”

[The Decolonizing Psychology conference was organized by Prerna Arora, Assistant Professor of School Psychology, in collaboration with two student leaders in the College's School Psychology program, doctoral students Kayla Parr and Olivia Khoo. Funding was provided by American Psychological Association Board of Educational Affairs, with additional support from TC’s Department of Health & Behavior Studies and Office of College Events.]

In a conversation moderated by TC Professor of Psychology & Education Laudan Jahromi, Mena confided that she grew up amid “a rich universe of non-Western cultural traditions” that included an amulet for warding off the evil eye, lighting candles “when you really wanted something to turn out well” and filling a bowl of water in the house to absorb bad energy or spirits.” Those traditions evolved over generations as responses to “cope, heal and alleviate the suffering of ordinary life and of colonization,” Mena said, and they continue to thrive today. But psychologists who grew up on those traditions rarely discuss them in professional circles for fear of being discredited as scientists.

“As a graduate student I observed a conflict in the moral codes between my home cultural values and psychology’s moral codes,” said Mena, co-author of Integrating Multiculturalism and intersectionality Into the Psychology Curriculum: Strategies for Instructors. “My home moral codes valued experiential knowledge, collectivism, family orientation and a pro-people attitude. In contrast, I saw psychology’s moral code as consistent with positivism, individualism, U.S. centrism and capitalism. And this discrepancy raised questions for me about my fit in psychology in general and in academia in particular.” The presence of many psychologists who do share her moral code, Mena said, has given her confidence that she does belong and equipped her with tools to fight against colonization. But the field today still presents “a psychology of predominantly White people who subscribed to a positivist, individualist US centric and capitalist perspective.”

Powered by the resonance of such ideas, The “Decolonizing Psychology” conference registered more than 5,100 people, drew upwards of 2,000 attendees at different points during the proceedings, and has since received more than 12,000 views.

Those numbers, said TC President Thomas Bailey in his opening remarks, “suggest that perhaps we have reached a potential watershed moment in the field, in academia and in this country,” and that “people of color and many other groups who have long labored against oppression are speaking and being heard.

“Events like this conference remind us that the movement for sustainable change is unstoppable and that history is on the side of inclusion, equity and social justice,” Bailey said.

— Steve Holt

[Read more on the Decolonizing Psychology Training conference: Challenging the Status Quo in Supervision; Reconceiving Mentorship; ‘All Research Is Political’; Sustaining the Momentum: After the conference, an ongoing focus on decolonization]