Schools in America are grappling with a range of challenges that can make it difficult to pursue educational equity, from funding uncertainty to the long-term effects of COVID-related learning loss. However, TC’s Alex Bowers, Professor of Education Leadership, and his co-principal investigators from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Richard Halverson and Christopher Saldaña, are working to change that by empowering school leaders to better leverage data.

The Comprehensive Assessment of Leadership Learning-Mapping Equity Indicators (CALL-MEI) project — a two-year study generously supported by The Wallace Foundation — seeks to develop information tools leaders can leverage in their decision-making. CALL-MEI is an expansion of the six-year Comprehensive Assessment of Leadership Learning-Equity Centered Leadership (CALL-ECL) project, which works with school leaders in eight major metropolitan areas to implement and support pipelines for equity-centered principals.

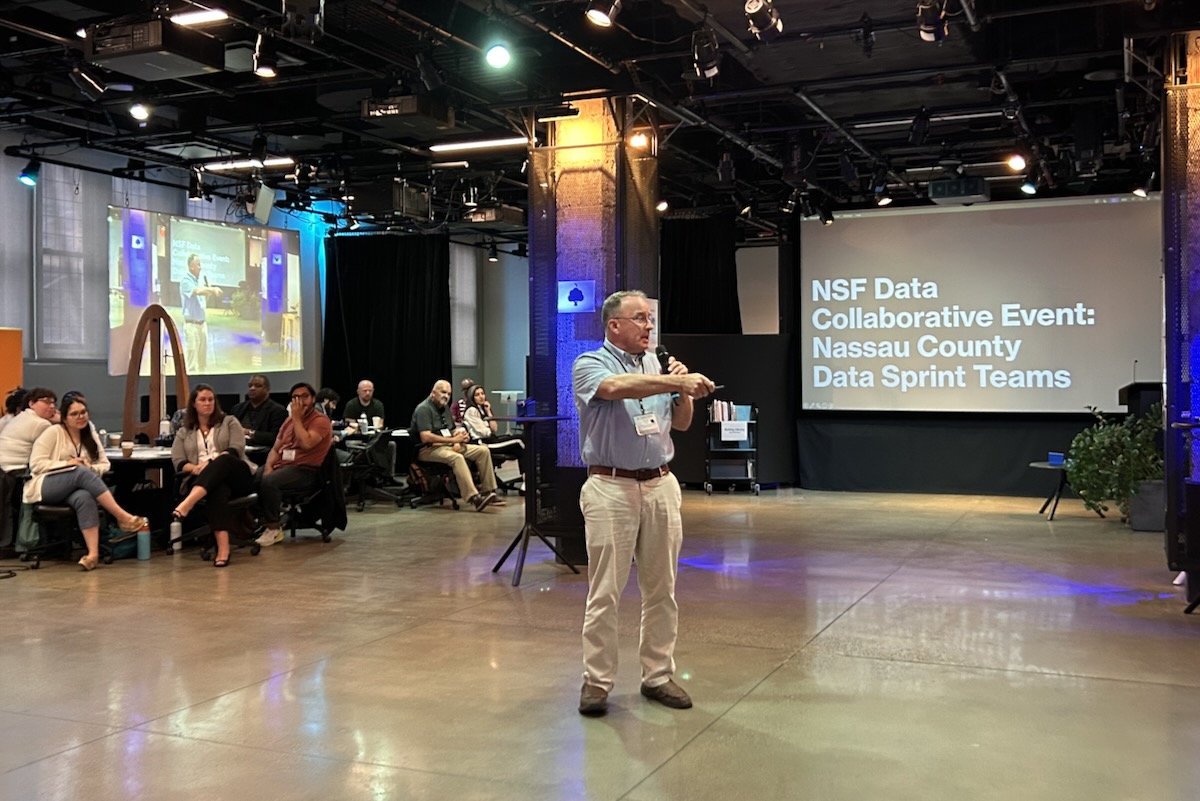

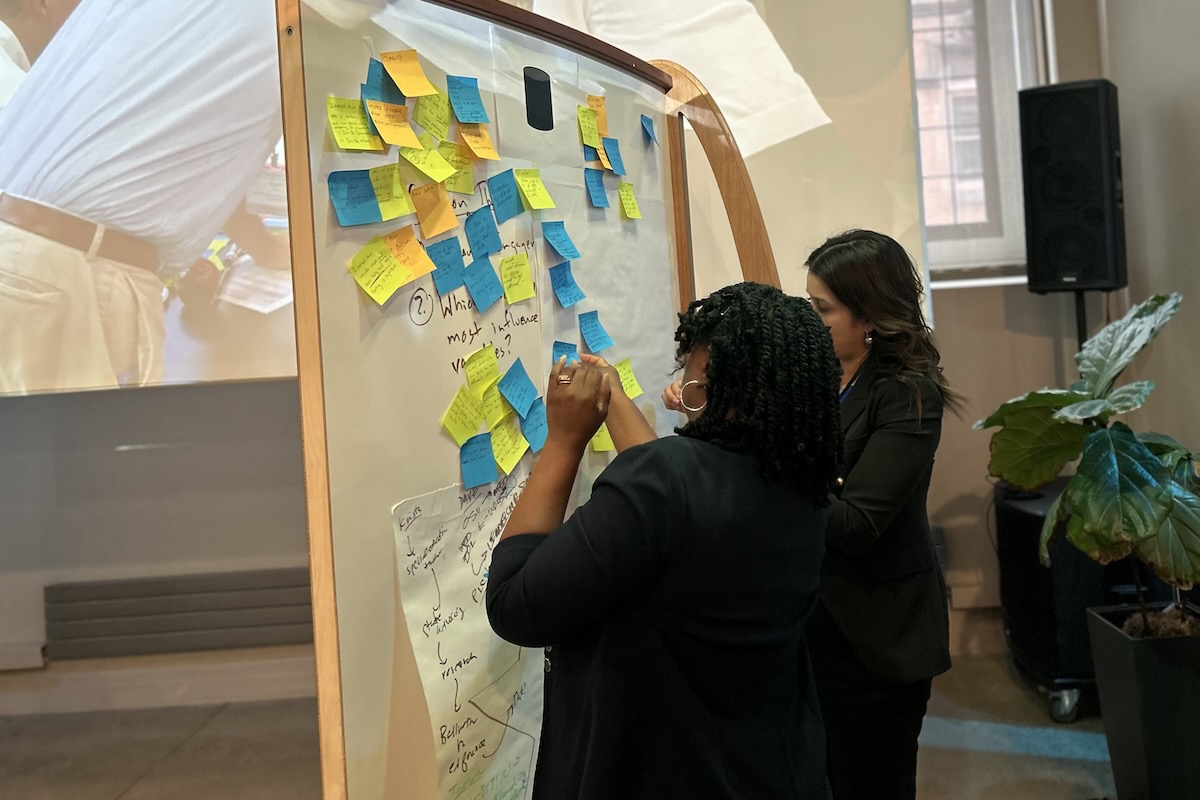

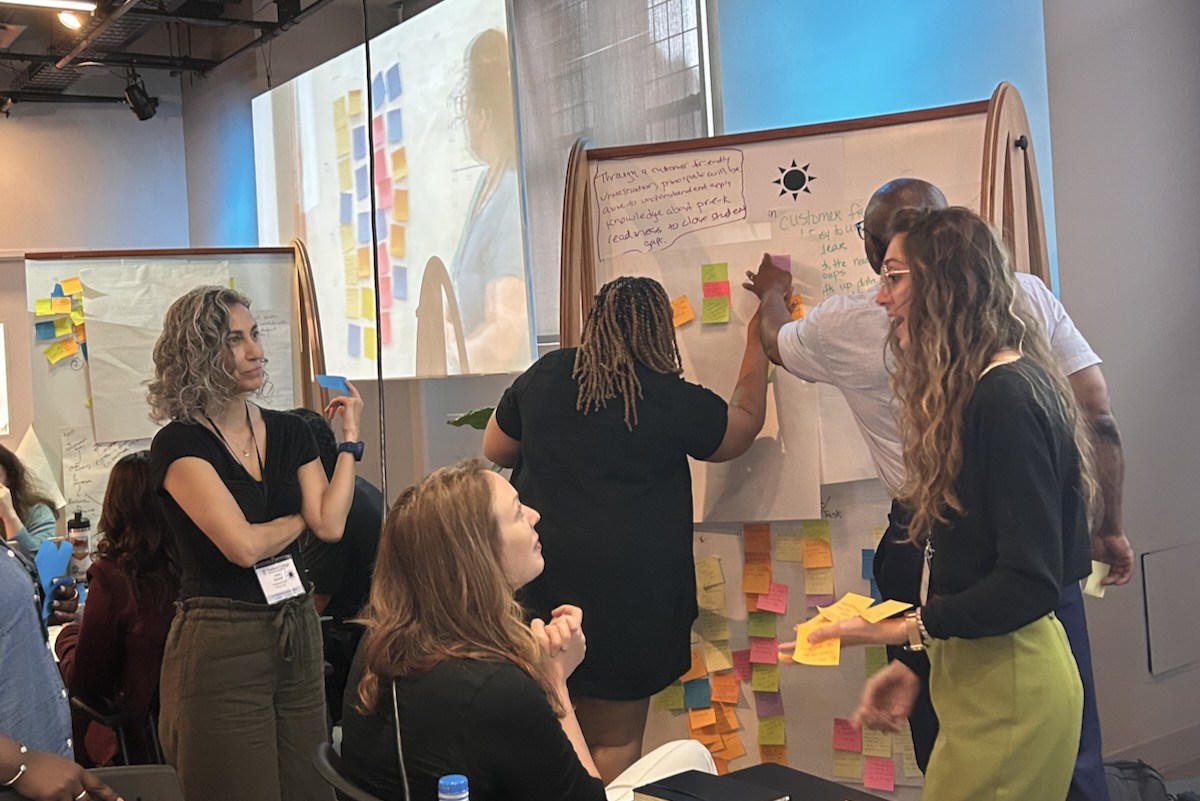

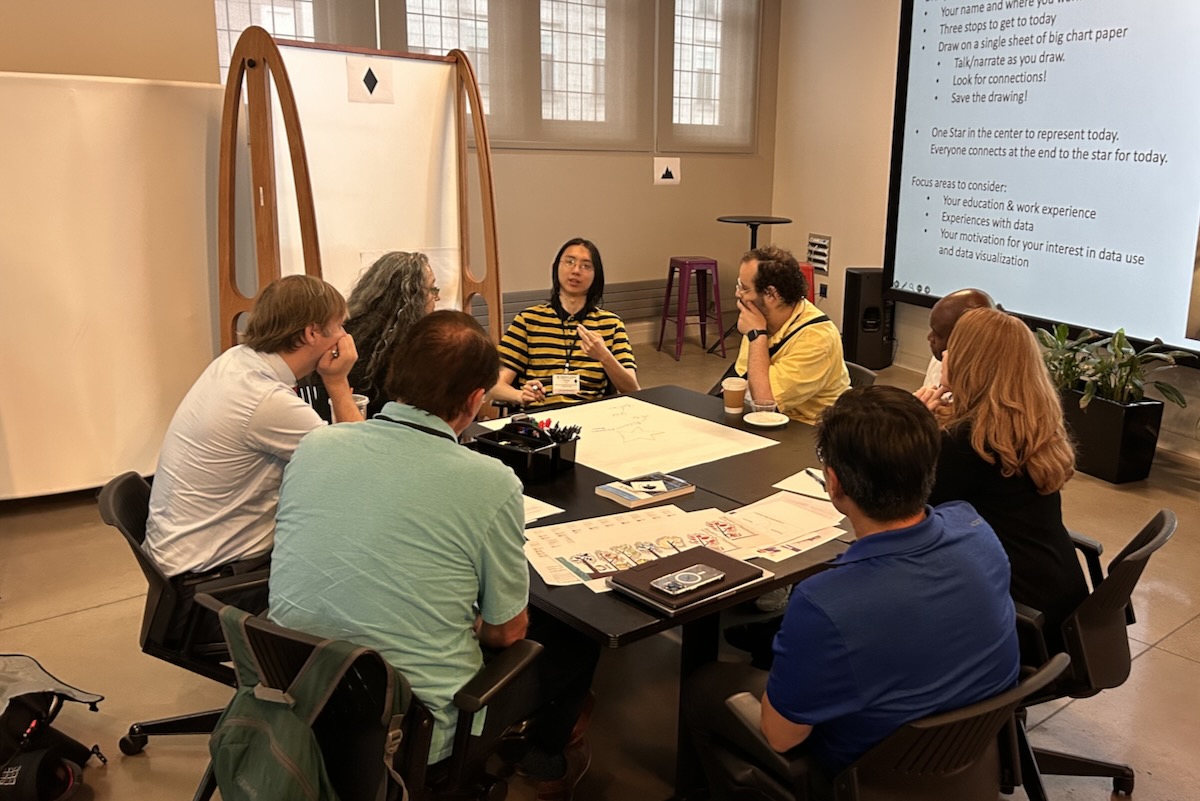

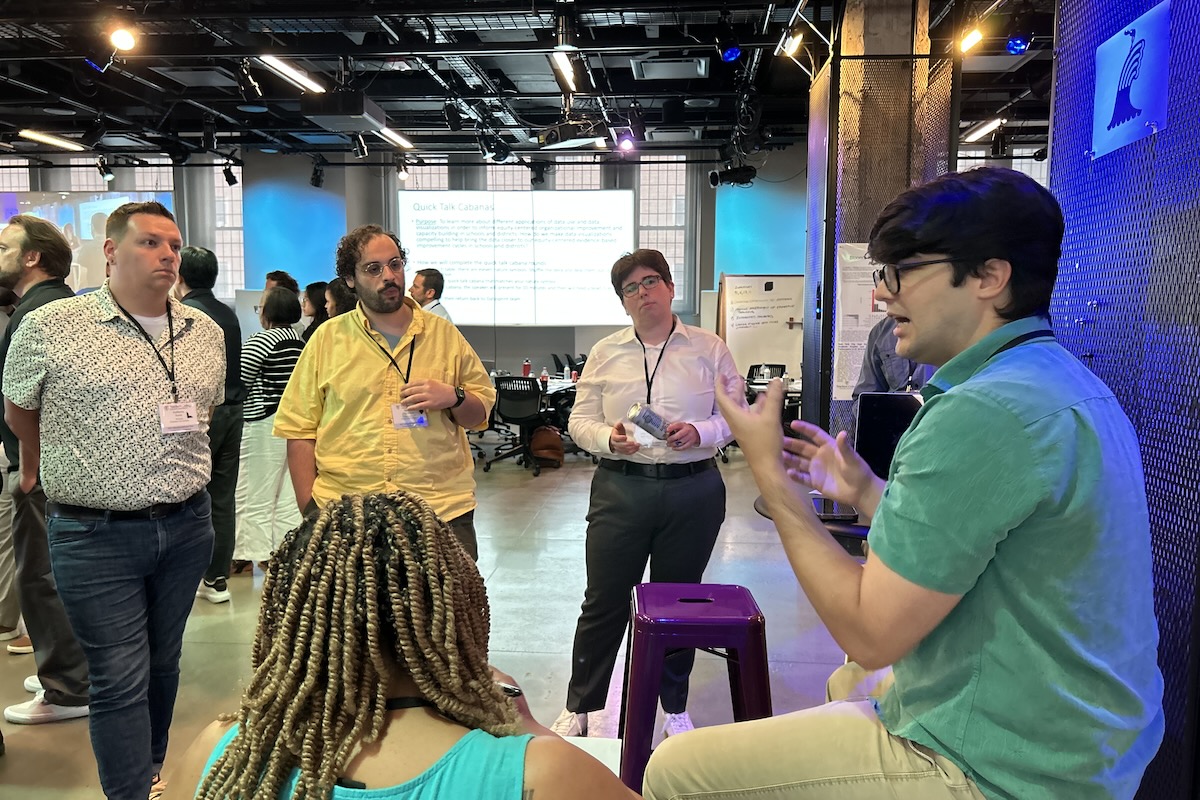

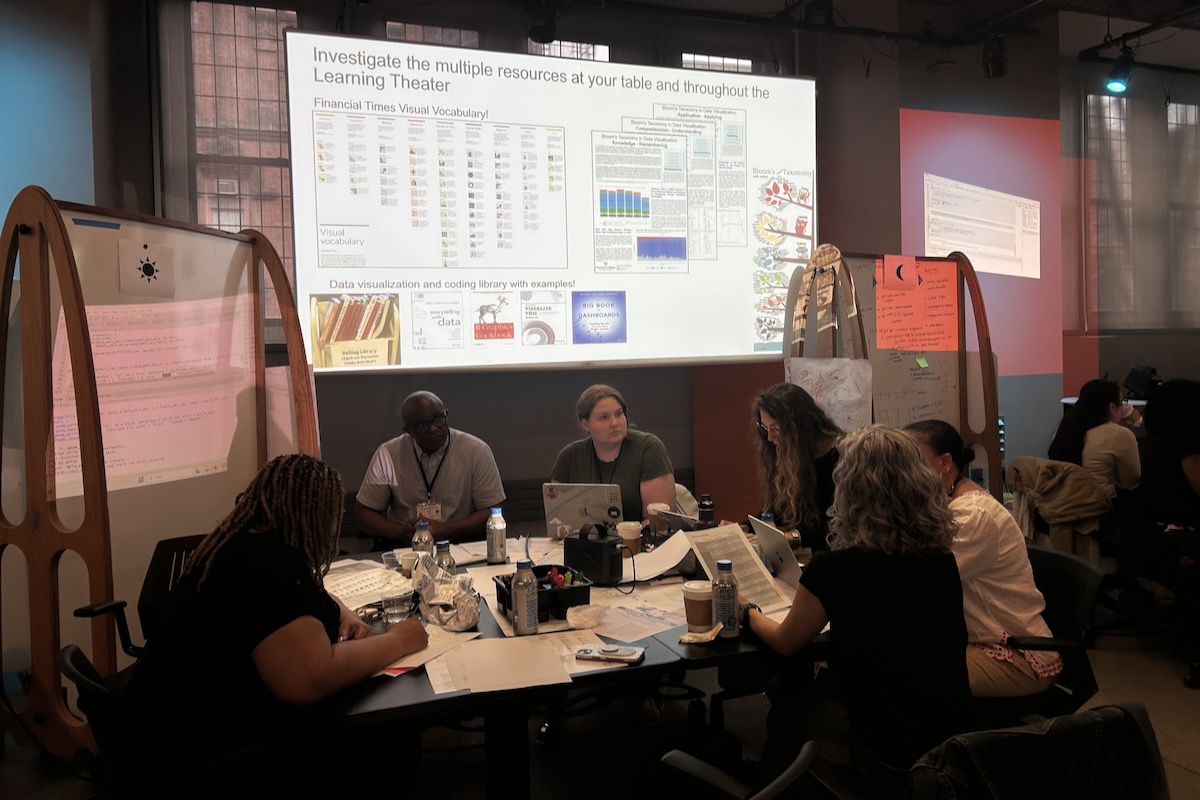

To help demonstrate the power of data, Bowers hosted the project’s data collaborative workshop at the Smith Learning Theater in June. School leaders spent two days immersed in the world of data analytics, learning from subject experts and each other to develop custom information tools using publicly available data from their districts. Fostering collaboration among workshop attendees — who worked in small data sprint teams — was a central focus for organizers because “data use is all about building relationships,” explains Bowers, who plans on publishing an e-book with insights from attendees. “The goal is to help expand this conversation so that there's an ability to not just exchange ideas, but also exchange data visualizations.”

Here are some key lessons learned at the data collaborative…

If inequity is present in schools, then support school leaders to change systems with data

Because schools are reflections of society, they also easily reproduce social inequities, according to Halverson, Professor and Kellner Family Distinguished Chair in Urban Education at University of Wisconsin-Madison. While robust teacher preparation and culturally inclusive pedagogies make a world of difference for students, creating and supporting pipelines for equity-focused school leadership is critical when it comes to changing harmful systems. “Equity-centered leadership uses data and critique to challenge current structures within the school and design new systems that provide opportunities for people who have been marginalized,” explains Halverson.

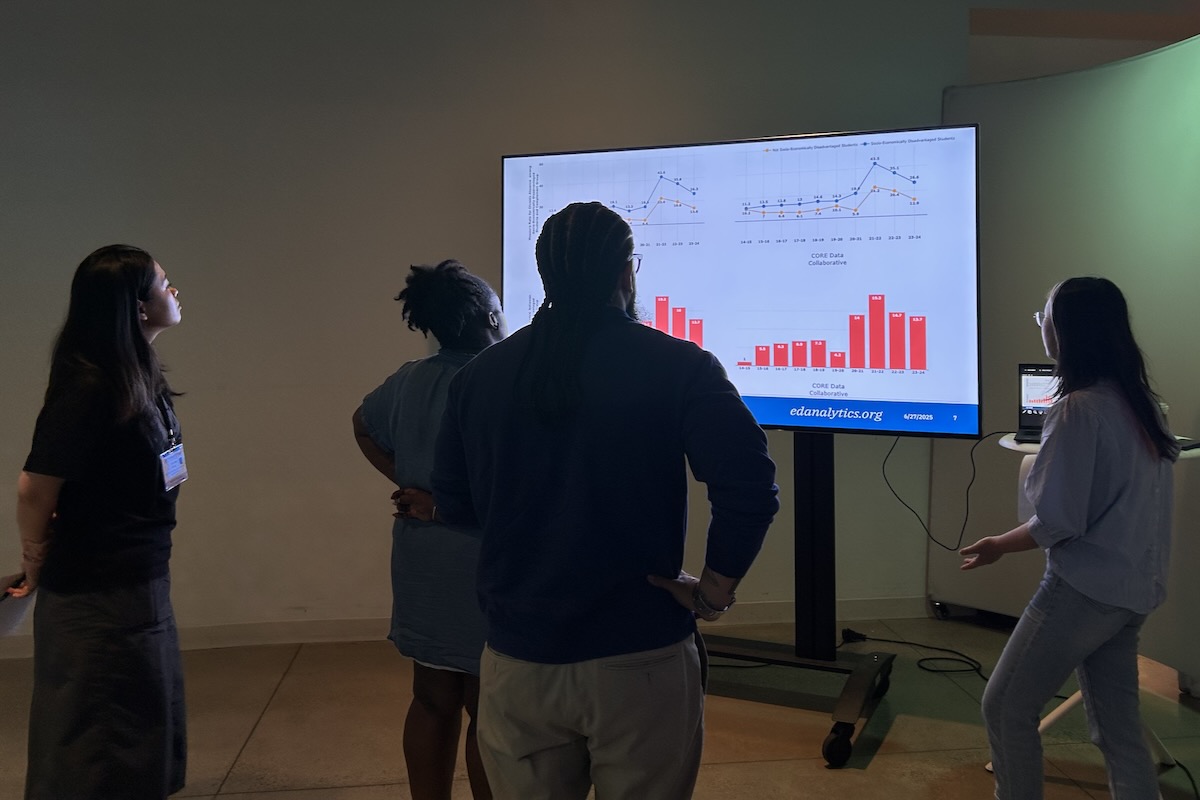

As part of the CALL-MEI project, which builds upon earlier research by Bowers, participants are encouraged to look at more expansive data sets, particularly the 16 data equity indicators identified by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. “I hope principals and district leaders start to realize that there are a number of different indicators [beyond] test scores that impact educational equity and improve the outcomes of kids,” says Saldaña, Assistant Professor of K-12 Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis at University of Wisconsin-Madison. “If we have data on students' wellbeing, how safe they feel at school or how connected they feel to their principals and teachers, that data could be a way to guide [decisions].”

If data dashboards aren’t connecting, then co-design with the end users

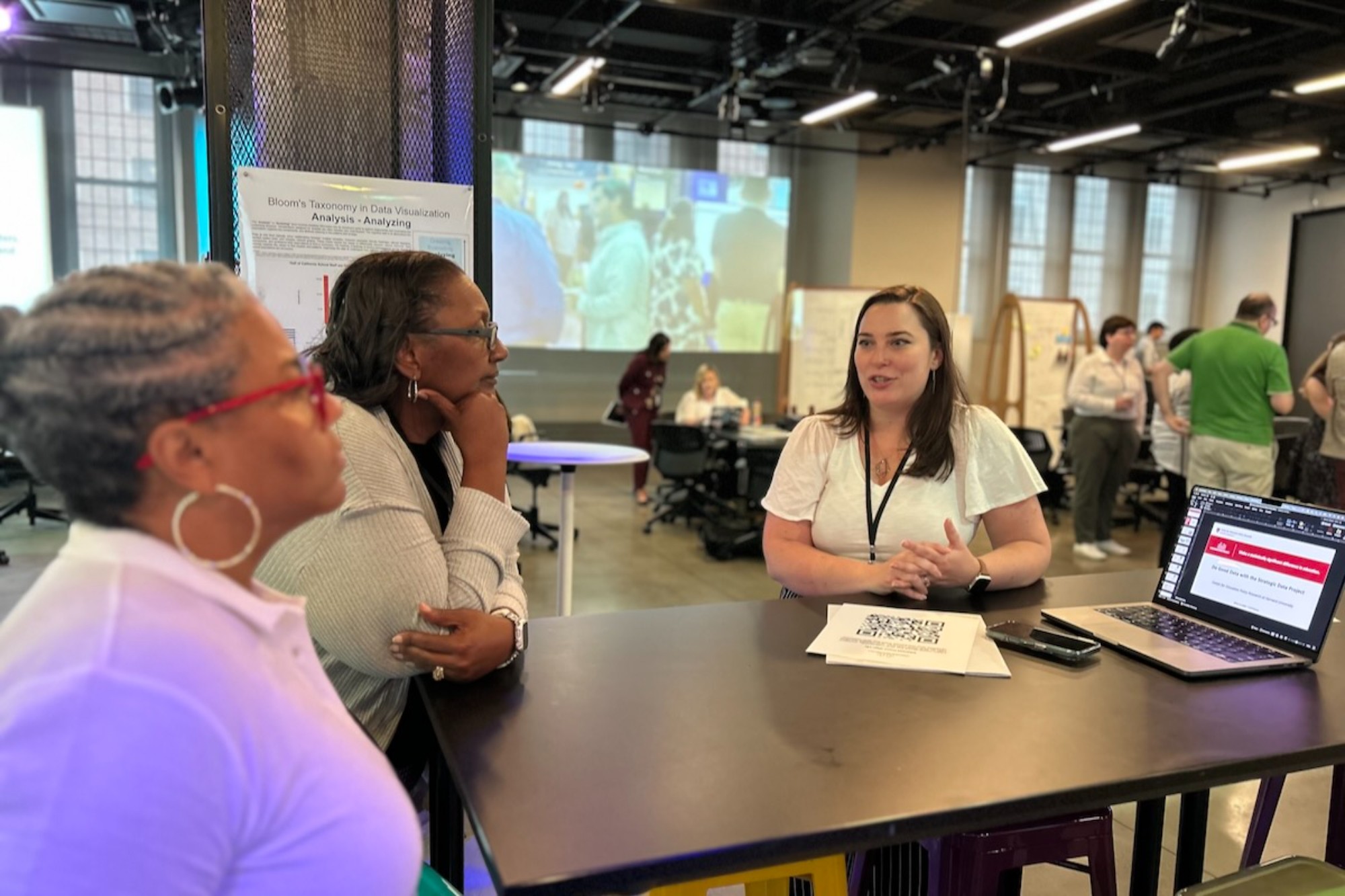

While data can be a powerful tool for change, data dashboards are often created for schools without input from users, resulting in analytic tools that rarely get used. “Data scientists know the data and they know the code, but they don't know what task needs to be addressed with the data visualization,” says Bowers, whose scholarship empowers leaders to leverage data to make schools more equitable. “The practitioners are the experts, we need to center their expertise.”

“The best of all worlds would be where those two groups of people — data report creators and the data report users — are immersed in each other but that's not usually how it's structured,” says Meador Pratt — Director/Executive Manager, Data and Management Services at Nassau BOCES Regional Information Center — a speaker at the 2025 data collaborative and attendee to a similar event hosted by Bowers in 2019. “I suggest that [they] think about ways that you can [have] conversations between the creators and end users be a normal part of your workflow.”

The task wrangling process, a favorite of Bowers, is a powerful method to bring data scientists and data users together. “You have dialogue on the issues that need to be visualized and you talk about what can be done,” he says. By having educators lead the design of data visualization tools, school leaders can craft data dashboards that are actually useful to their work.

If data can be biased, then know that people have power, not numbers

Some people — including some data analysts — believe that data is inherently neutral. However, data can not only carry bias, it can be easily manipulated and used to enact long-lasting harm. A simple way to avoid this pitfall, beside awareness of interpretive bias, is to keep in mind that data cannot stand alone. “Analytics in and of themselves are just a tool, you are what translates data into action” says Brandi Hinnant-Crawford, Associate Professor of Educational Leadership, Clemson University and keynote speaker at the data collaborative. “We have to recognize that the ingenuity to address the issues facing our schools lies within the people in our schools.